Published :

Updated :

How is it that Bangladeshis save, yet the country is not truly becoming wealthier? Why does so little of that hard-earned money find its way into productive ventures, businesses, or the capital market? What is stopping Bangladeshis from moving from "saving for safety" to "investing for growth"?

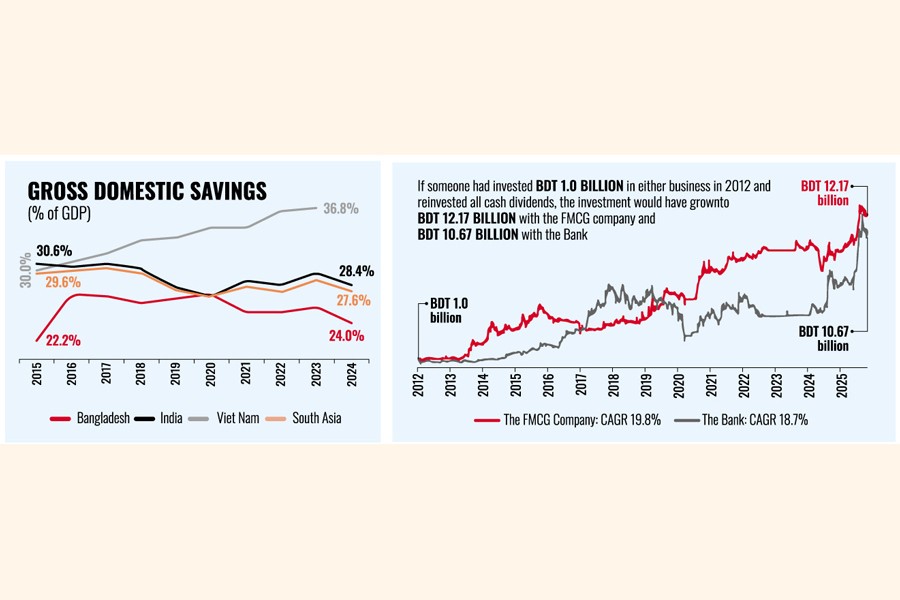

Bangladesh had nearly closed the savings gap which is gross domestic savings as per cent of GDP with its South Asian peers a few years ago, but the persistent inflation has partially eroded real disposable incomes and household saving capacity.

Yet, the funds that are saved rarely translate into productive investment. A significant share remains locked in low-yield bank deposits or government savings instruments such as Sanchayapatra, safe, fixed-return products that do little to fuel capital formation or private-sector growth.

To make matters worse, savings parked in deposits are losing value. In August, the weighted average deposit rate was 6.39 per cent, while inflation hovered at 8.29 per cent. Anyone relying only on bank deposits actually lost a part of their real wealth during this high-inflation period.

One way to understand how little we invest is to look at a popular global investment vehicle: mutual funds. In many developed markets, mutual funds are the backbone of household investing. Countries like the United States, Australia, the Netherlands have mutual fund assets worth more than 100 per cent of their GDP. In India, this figure stands at 19.9 per cent. Even Pakistan, with a smaller economy and financial system, has crossed 2 per cent.

But Bangladesh? Our total Mutual Fund Asset Under Management is barely around 0.15 per cent of GDP.

Good Saving Habits, Weak Investment Ecosystem

This imbalance, between the willingness to save and the reluctance to invest, lies at the heart of Bangladesh's shallow capital market and limited household wealth creation. The challenge runs deeper than just mindset; our investment ecosystem itself is thin, with well-governed companies having little to no incentive to be enlisted. When the supply of good listed companies is limited, it becomes harder for households to trust the market as a reliable wealth-building avenue. This shortage is compounded by a long-standing trust deficit. The 2010 market crash may have left deep scars, and for over a decade, the market swung between brief recoveries and prolonged declines, leaving most retail investors with the impression that stocks are unsafe, and "investing" feels risky, even speculative, to the average saver. Episodes of manipulation, governance lapses, and a lack of investor protection only strengthened this perception, and trust, once broken, takes time to rebuild.

The capital market's limited role becomes clearer when we compare market depth. India's market capitalisation is now 142.11 per cent of its GDP. Vietnam's market cap stands at 42.95 per cent. In contrast, Bangladesh's market capitalization to GDP ratio was only 11.93 per cent in FY'25, a shallow market for an economy of our size and ambition.

Low investor participation, fuelled by weak financial literacy, limits market growth, ultimately constraining the market depth. Our education system rarely teaches the very basics of personal finance. Most people do not learn about inflation-adjusted returns, diversification, mutual funds, bonds, or long-term compounding. Without this foundation, savers are almost forced to remain savers.

And even if they do enter the market, many fall into herd behaviour rather than informed decision-making. Noise frequently replaces research; "hot tips," rumours, and short-term hype overshadow business fundamentals, cash flows, or long-term value.

The Short-Term Trap and the Cost of Impatience

These existing obstacles compound with the short-term mindset of ours, which shapes how we save and invest. A significant portion of bank savings is held in categories that are shorter-term or easily accessible. Yet, to drive sustainable economic growth, the financial intermediaries need the capacity to extend long-term financing to businesses and infrastructure. This creates a maturity mismatch in the financial system; short-term money is expected to fund long-term economic growth. When depositors want quick liquidity, it limits the ability to channel funds into long-term productive investments. If households were willing to invest with longer horizons, more capital could flow to businesses, job creation, and innovation.

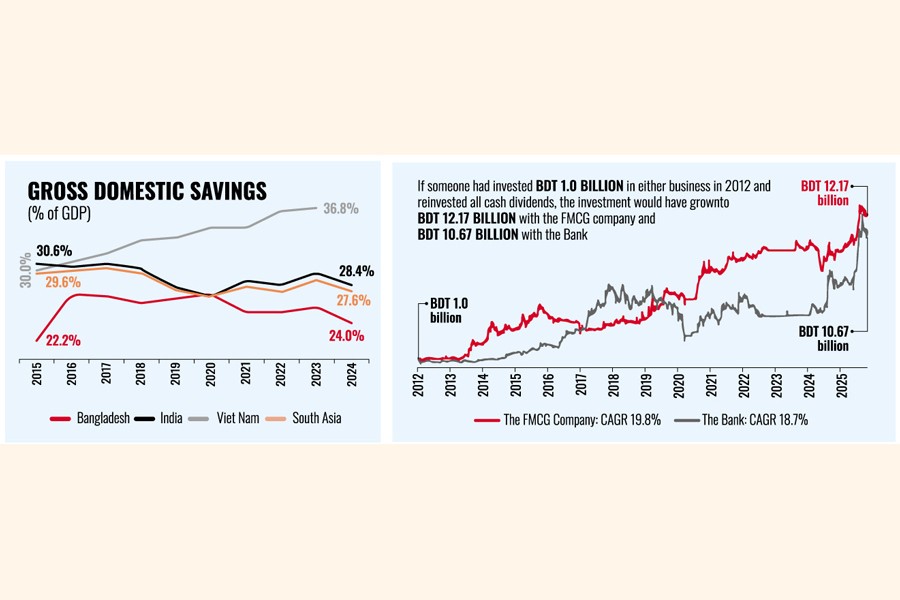

This short-term thinking is equally visible in how we view the capital market. Many people expect quick gains and become frustrated or overwhelmed by looking at short-term price movements. A well-established listed FMCG company, for instance, may seem unattractive if someone looks only at the last three months' price performance or return: it will show a loss of 0.5 per cent.

But investing is a long-term game, and returns also depend heavily on the quality and governance of the business one invests in. The FMCG company mentioned earlier is a well-governed, fundamentally strong company with consistent business performance. Had someone invested BDT 1.0 billion (100 crore) in that business back in 2012, reinvested all the cash dividends, and simply held it, the investment would be worth roughly BDT 12.17 billion (1,217 crore) today, more than 12 times the original investment without needing to jump from share to share.

The difference becomes even clearer when compared to traditional savings returns. Had someone invested in one of today's leading private commercial banks back in 2012 and reinvested all the cash dividends, the investment would have grown tenfold, delivering a CAGR of 18.7 per cent, far higher than any deposit rate offered by the same bank. Both the returns could have been achieved because the underlying business was strong, not by speculation.

The lesson is simple: wealth is not created by reacting to rumours, noise, and short-term fluctuations, but by patiently holding quality assets. Until we shift from a saver's habit of "quick access, low return" to an investor's mindset of "long-term growth and compounding", will our own financial health improve?

India's Blueprint: Convenience and Awareness

Now this may naturally raise the question: If Bangladesh is still stuck at the saver stage, how has India already moved toward becoming an investor-driven country? If we had to simplify the answer, two forces stand out: convenience and awareness.

India's transformation was multi-channel, not a single initiative, but an ecosystem shift. The first layer was digital and financial inclusion. Aadhaar gave citizens a verified digital identity; the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) brought millions of unbanked people into the formal banking system; and the launch of UPI in 2016 revolutionized payments and built everyday familiarity with digital money management. Convenience came first, and with it, comfort.

With the infrastructure in place came the awareness push. In 2017, the Association of Mutual Funds in India (AMFI) launched the now-iconic "Mutual Funds Sahi Hai" campaign, a nationwide initiative aimed at simplifying investing for ordinary households. It did not merely advertise mutual funds; it demystified investing and reframed mutual funds as safe, disciplined, and goal-oriented. India strengthened the investment culture with policies such as differentiated tax treatment for longer-term investments to promote holding investments for more than a year, rather than frequent short-term trading.

The results speak for themselves. India's demat (BO) accounts grew from roughly 20 million (2 crore) in 2014 to more than 190 million (19 crore) by FY2025, a nearly tenfold increase in a decade, reflecting a cultural shift from saving to investing.

The Path Forward: Accountability and Awareness

It is not like Bangladesh is standing still. Bangladesh Securities and Exchange Commission (BSEC) is advancing new rules for Public Offerings of Equity, Margin Rules, and Mutual Fund regulations to emphasize stronger governance and investor protection. BSEC has also taken stricter enforcement actions against capital market intermediaries and market manipulators, issuing fines and penalties for capital market violations like misuse of BO accounts and price manipulation. These actions signal a stronger regulatory stance and a shift toward accountability in the market. When such punitive steps, bans, large fines, and mandatory fund restitution are enforced, investor confidence can begin to rebuild.

Beyond regulation, Bangladesh already has tax incentives to tilt behaviour towards productive investments. Under the Income Tax laws, individuals receive investment tax rebates for eligible investments, though the maximum

allowance is capped and amounts vary. Direct investment in the capital market and investment in a mutual fund up to BDT 500 thousand (5 lac) qualify for a tax rebate. At the same time, capital gain up to BDT 50 lac is tax exempted.

Ultimately, the shift from a nation of savers to a nation of investors requires efforts on both sides. Individual willingness must meet systemic support. Households need to gradually move away from the comfort of short-term parking of money and embrace longer-term wealth-building habits. But the system must also make that journey easier, with transparency, convenience, investor protection, and financial education.

For individuals, this is a uniquely favourable moment. Interest rates are attractive for locking in high-yield fixed-income investments, and the equity market currently offers opportunities to buy well-governed, fundamentally strong businesses at undervalued prices.

If we take inspiration from India's success, the lesson is clear: digital convenience and mass awareness change behaviour. For those who do not have the time or expertise to research and manage portfolios, mutual funds, and professional asset managers exist for that very reason. Wealth compounds only for those who give it time. If we want our savings to truly grow into prosperity, we must learn to let our money work for us: not for just a few months, but for years.

Starting small is never the problem; staying patient is.

Irtifa Raiyan is an Investment Analyst at UCB Asset Management, She can be reached at

irtifa.raiyan@ucbasset.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.