Dormant industry can drive country's export diversification

Animation industry holds $3.0 billion export earnings potential

Entrepreneurs seek policy perks to make it happen

Published :

Updated :

Bangladesh's animation industry, still a niche player on the global stage, holds the potential to fetch as much as US$3.0 billion in annual export if given the right policy support, industry-insiders claim.

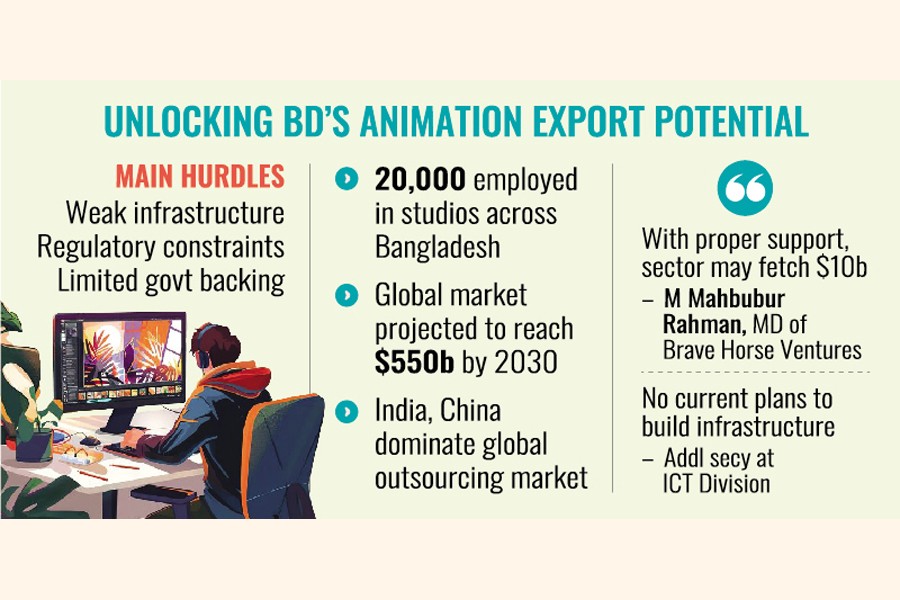

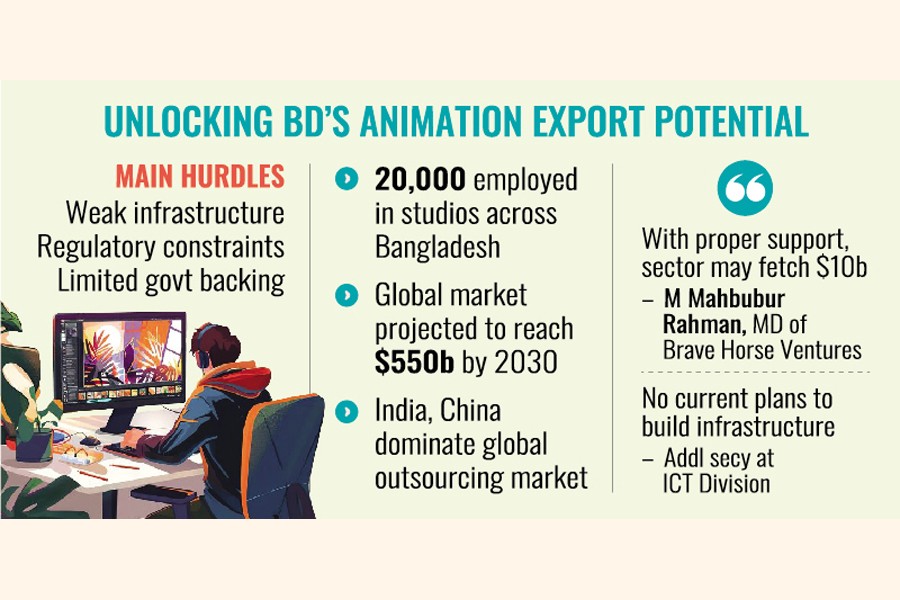

For more than a decade, Bangladeshi animators have quietly been producing high-quality works for global entertainment giants. Yet, despite their brains, the sector has struggled to emerge as a standalone export earner, hampered by weak infrastructure, regulatory constraints and limited government backing.

The timing for expansion could not be more urgent. Globally, the animation market is booming nowadays. Analysts expect it to reach $550bn by 2030, propelled by the rise of streaming platforms, video games and demand for visual content.

Industry advocates believe Bangladesh has a window of opportunity to capture a share of this growth cake in the fastest-growing knowledge economy of digital era.

"With the right steps and policies, Bangladesh can turn animation into another significant export-oriented sector," says M Mahbubur Rahman, managing director of Brave Horse Ventures, which has partnered Malaysia's Vav Productions. "This sector could fetch $10bn in the near future if it gets proper support."

At present, around 20,000 people are employed in animation studios across Bangladesh. With nearly 28 per cent of the country's population under 30, supporters argue the industry could provide badly needed employment and diversify an economy still dominated by the decades-old garment trade.

But the hurdles are considerable. Animators complain of high production costs, particularly the lack of shared rendering houses - the powerful computer hubs essential for animation. Studio owners also face restrictions while hiring foreign experts, a necessity in an industry where international collaboration is often critical.

"At present, paying foreign employees is extremely complicated," says economist Dr Abdur Razzak. "In many countries, entrepreneurs can pay foreign staff directly thanks to convertible capital accounts. In Bangladesh, that is difficult because of the risk of misuse and the fragility of foreign reserves."

The lack of a supportive regulatory framework has meant investment has lagged. Brave Horse's joint venture with a Malaysian production house remains the exception rather than the rule. "With the right system, Bangladesh could attract far more foreign investment," Mahbubur told The Financial Express.

So far, the government response has been muted. An additional secretary at the ICT Division acknowledges that "there are no current plans" to build infrastructure for the industry. Projects may be taken up after the next government is in place, he says.

To industry advocates' mind, this hesitation risks squandering a generational opportunity. "The growth of this sector is being held back by a lack of resources," says IT expert Sohael Reza. "We need infrastructure, advanced tools, training facilities and fewer policy constraints. Otherwise, Bangladesh risks being left behind."

Regional rivals India and China already dominate the global animation-outsourcing market, leveraging scale, policy support and investment. Bangladeshi studios, by contrast, remain underfunded, despite being able to offer animation at lower prices than many competitors.

Still, there are signs of optimism. The rise of digital platforms has given Bangladeshi animators new avenues to showcase their work. "This is a golden opportunity," says Mahbubur.

"We have thousands of young animators ready to work. But without support, they will end up working for overseas companies instead of building our own industry."

Youth unemployment remains high: around two-thirds of graduates are unable to find work each year. Advocates argue that animation, if nurtured, could absorb part of this workforce while showcasing Bangladesh's creative capacity.

The sector is not entirely new to the game. Bangladesh's first animation courses were introduced in the 1980s, and the UNICEF-backed Meena cartoon series, launched in 1993, became a cultural landmark across South Asia. But since then, progress has been slow and fragmented.

Industry leaders say the lesson is clear. "It's not just about producing content," says Dreamer Donkey CEO Mosiur Rahman Choudhury, "It's about building an ecosystem for innovation and collaboration.

If government, private studios and investors can work together, Bangladesh can carve out a niche on the global animation market."

For now, the sector remains stuck between promise and policy inertia. With global demand surging, the question is whether Bangladesh will seize the moment - or once again watch from the sidelines as others lead the way.

mirmostafiz@yahoo.con

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.