Published :

Updated :

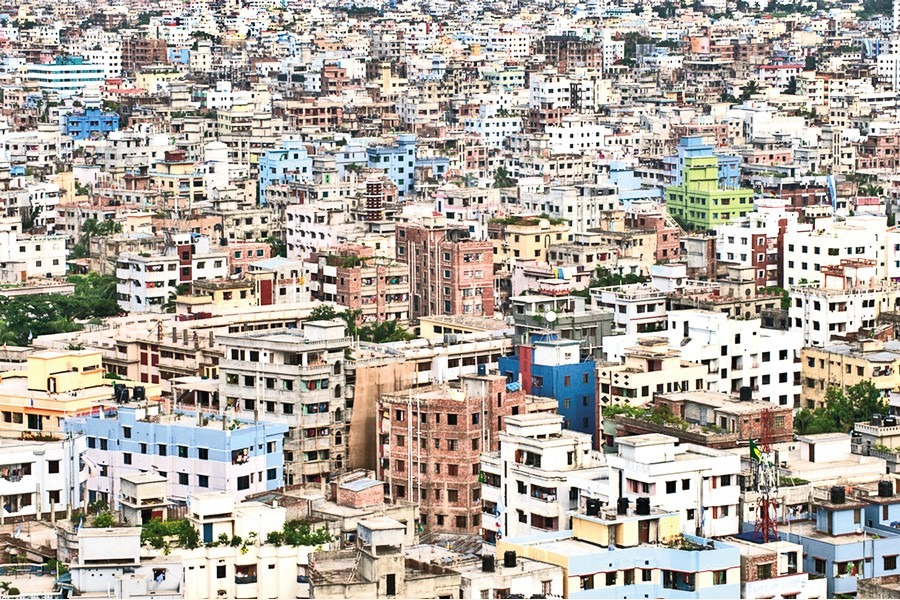

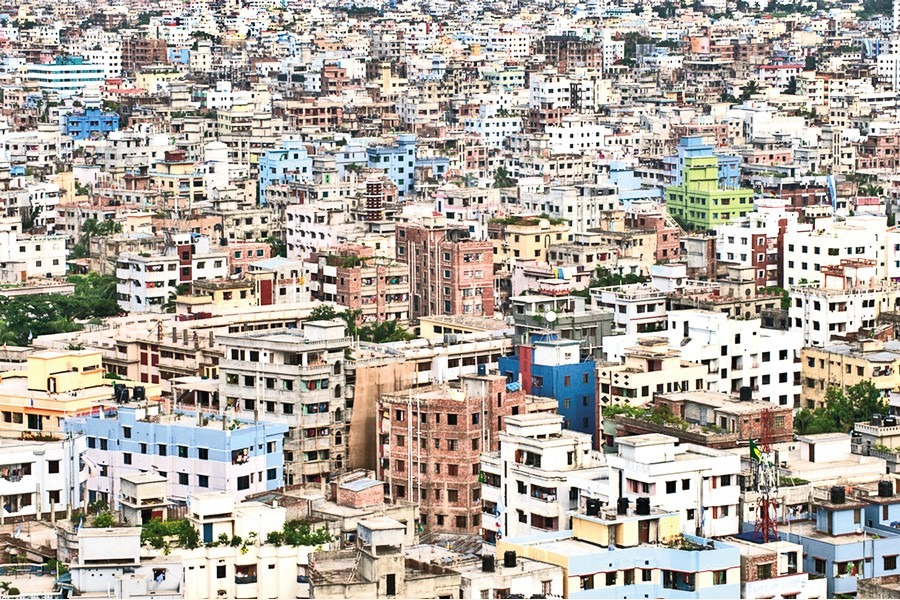

The long awaited national election, held 17 years after the last genuinely contested vote, has brought with it a wave of public expectation. For many residents of Dhaka, some of those expectations are surprisingly simple, though no less reasonable for it. People in the megacity want a clean and orderly place to live where essential civic services actually work the way they're supposed to, which really should not be too much to ask. When Dhaka City Corporation was split into two administrative units in 2012, the idea was to make management easier and services more efficient. The plan seemed practical and promising at the time. Managing a smaller area was expected to be simpler, and citizens were supposed to see improvements in services and coordination. Nearly two decades later, the outcome has not matched what was intended. Yet nearly two decades later, the lived reality suggests that it has not delivered the intended outcome. Instead of the orderly and well-maintained look that is common in many capital cities, Dhaka often seems stretched to its limits, struggling to meet even the most fundamental standards of urban management.

The most obvious sign of this failure is the persistent problem of waste. Roads, lanes and public spaces frequently remain littered with garbage, creating not only an unpleasant environment but also a serious public health concern. Part of the problem comes from limited infrastructure, as the lack of convenient waste disposal points leaves many residents and businesses with little choice but to leave trash on the streets. At the same time, irregular collection schedules and weak monitoring allow waste to accumulate, sometimes covering portions of the road. The consequences go beyond aesthetics. Accumulated garbage contributes to clogged drains and waterlogging, making daily life in the city even harder. However, it would be unfair to blame the city authorities alone. Public behaviour plays a significant role, as many people continue to dispose of everyday items carelessly, turning freshly cleaned streets into dumps within hours. Without a change in civic habits, even the most efficient system will struggle to maintain cleanliness.

Urban disorder in Dhaka is further compounded by the widespread occupation of footpaths by hawkers and informal vendors. In many parts of the city, footpaths have turned into extensions of informal markets where goods are displayed, sales take place and semi-permanent stalls are set up. This adds to congestion and often pushes pedestrians onto busy roads. It is widely understood that such occupation does not occur by chance but is often sustained by informal payments and tacit approval from segments of enforcement agencies. At the same time, the economic side of the issue cannot be ignored. For many small traders, vending on footpaths is one of the few affordable ways to participate in the city's economy. Any attempt at removal that fails to consider this dimension risks being both ineffective and socially disruptive.

The new government faces a clear test of its will when it comes to problems like footpath encroachment and basic cleanliness. Waste management needs to be strengthened through better infrastructure, regular collection and stricter penalties for people who dump rubbish just anywhere. At the same time, there has to be sustained public awareness so that people understand their own role in keeping the city clean. As for the footpaths, the solution has to be balanced. Pedestrian space must be protected, but there should also be designated areas where small traders can operate in an organised way. If the government wants to deliver on its promise of better urban life, focusing on cleanliness, order and discipline must be among its top priorities.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.