Published :

Updated :

"Reading stamina really is a thing. I used to read entire chapter books within a few days, but after a year-long break from reading, I can barely read for an hour and now finish books in a week or more." This isn't the story of one individual; it reflects the experience of many today. According to a recent survey conducted by CEO magazine, Bangladesh ranks 97th among 102 countries, with a yearly reading hour of only 62, which is significantly lower than Syria, Niger, Cambodia, Zimbabwe, and Myanmar. India is second in the list. Why does this happen? Most important, does Bangladesh even bother about this?

The contemporary learning environment, where PowerPoint presentations often replace chalkboards, is heavily reliant on visual lectures that use bullet points. This convenient delivery method has automatically minimised the need for students to interact closely with books.

At the same time, the internet culture of TL;DR (Too Long; Didn't Read) and AI-based summarisation tools has severely impaired reading comprehension. Why invest time in reading an entire book or even a paragraph when a concise summary offers the essential information?

This constant barrage of instant information is causing the current generation to lose the capacity for deep reading, a concerning development particularly evident in Bangladesh.

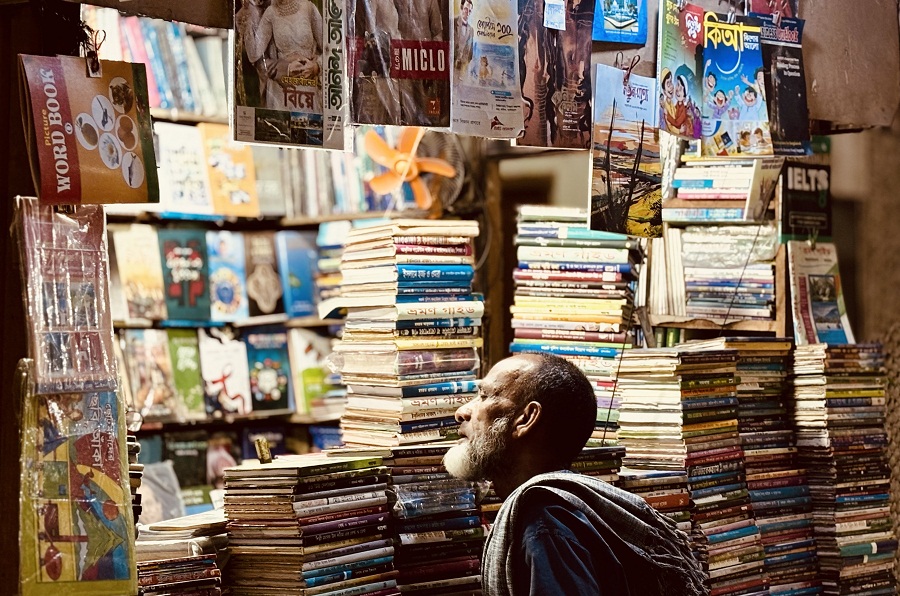

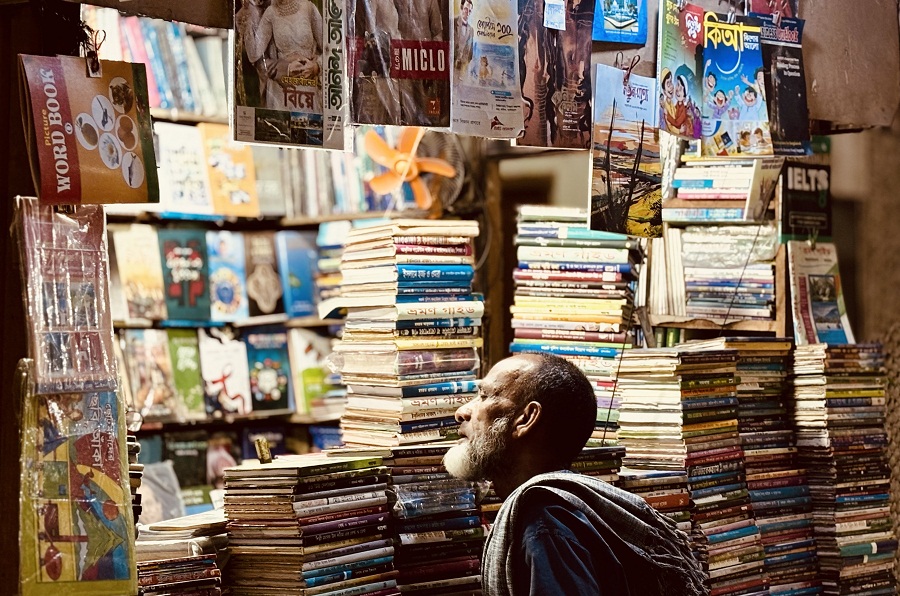

Once home to a proud literary heritage, Bangladesh now struggles to maintain a culture of reading.

With a population of over 170 million, the country boasts a rich literary heritage from the poetic epics of Rabindranath Tagore to the gritty realism of Humayun Ahmed. Access to affordably priced books is limited, compounded by the fact that illiteracy in rural areas remains at approximately 25 per cent; consequently, reading is primarily a privilege enjoyed by urban elites.

For Bangladesh, the numbers sting. A nation that gave the world Rabindranath Tagore's poetic brilliance and Humayun Ahmed's heartfelt novels now sees its youth spending 3.5 hours daily on social media.

At the same time, books gather dust in rural areas. Libraries are a rarity; only 15 per cent of villages have access, and a book can cost 10-20 per cent of a daily wage. Even in cities, the celebrated Ekushey Boi Mela draws crowds, but only 25 per cent of attendees read regularly. The question looms: how did a nation with such a rich literary heritage drift so far from the page?

The issue goes deeper than statistics; it's about what kind of relationship a society builds with books. The educational structure in Bangladesh prioritises rote memorisation over fostering creativity and innovation. Students are driven by the need to pass examinations rather than a desire for genuine exploration and learning. Such a thought process poses a severe threat to the younger generation, given that critical thinking and effective communication, both of which are fostered by regular reading, are indispensable skills for daily living.

According to Save the Children (2024), only about 30 per cent of Bangladeshi primary students read for pleasure, compared to 65 per cent in India. Without early emotional connections to stories, reading can become a task rather than a joy.

Then comes the screen. With over 70 million smartphone users, Bangladesh has entered a digital whirlwind. "Kids scroll for hours but won't spend five minutes with a book unless it's for an exam."

And yet, this isn't an isolated problem; neighbouring nations wrestle with the same tug-of-war between literacy and technology. The difference is that India managed to turn digital tools into allies: vernacular e-books, affordable subscriptions, and storytelling apps have made reading accessible to millions.

The future workforce will live surrounded by synthetic output. What will distinguish great talent is the ability to add something human: imagination, interpretation, and perspective.

Tagore once wrote, "The butterfly counts not months but moments, and has time enough." In a world obsessed with speed, reading is a radical act of slowing down, of savouring moments that spark imagination.

Bangladesh's literary heritage is not a relic to be mourned but a flame to be rekindled. By making books accessible, education engaging, and technology an ally, the nation can reclaim its love for the page and ensure that the next generation doesn't just scroll through life but lives it, one story at a time.

mahdiabzaman@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.