COURTS CROWDED WITH LITIGANTS!

Apex court heaving under logjam of half-million cases

Nearly 4.3m cases pile up in all courts till 2023

Published :

Updated :

A decade of steady case disposal falls short of a pace warranted to deal with a logjam of cases Bangladesh's apex court faces amid a rush of litigants in courts across the country, sources say.

A predominant feature in the piling up of pending cases is numerous cases implicating several hundred accused each--some standing high-profile persons in the dock.

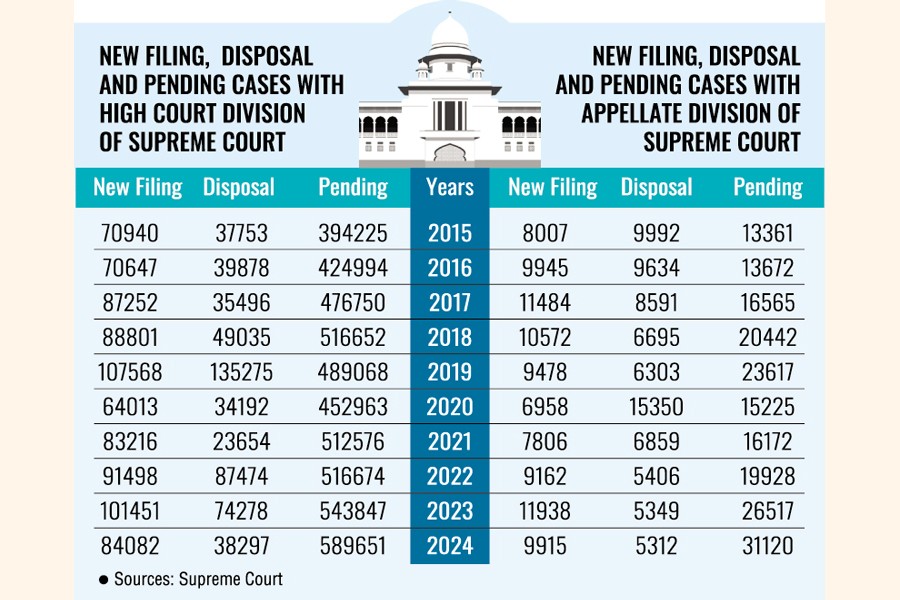

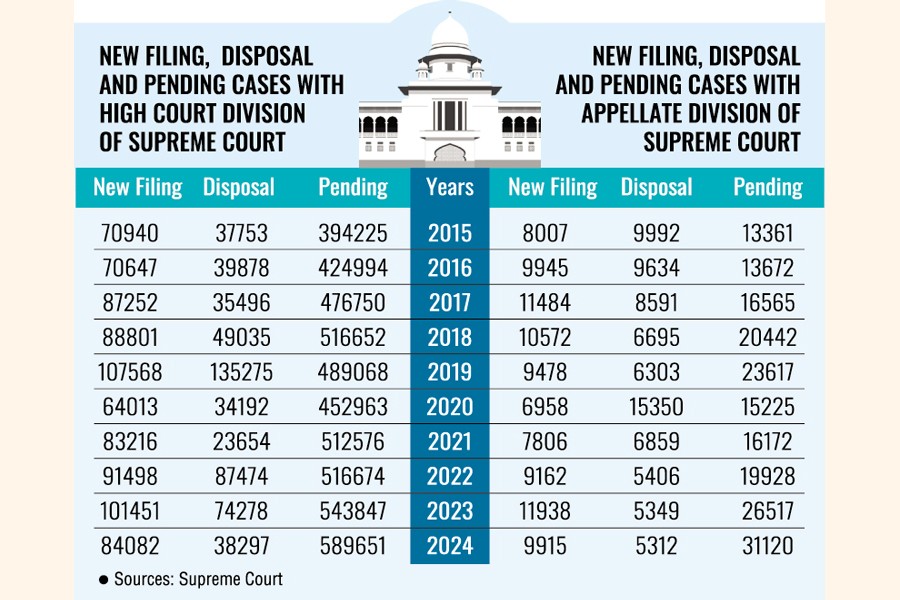

Between 2015 and 2024, more than 849,000 cases were filed in the High Court Division and over 95,000 in the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court, while the number of disposals fell short to cope with the pressure, leaving hundreds of thousands of cases pending for years.

By the end of 2023, nearly 4.3 million cases had remained pending across all courts, with the bulk in district-level courts, according to sources close to the judiciary.

Of the total, 26,517 cases were pending with the Appellate Division, 543,847 with the High Court Division, and 3,729,235 in the district-level courts.

The arithmetic of litigation mirrors amply the depths of pressure on justice-delivery system in the country.

In 2023, a total of 2,003 judges were actively serving in the country's subordinate courts, collectively disposing of 1,337,123 cases during the year. On average, each judge handled and settled around 668 cases, covering both civil and criminal matters.

Since 2015 till 2024, a total of 95,265 cases had been filed with the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court, while 79,491 were settled during the period. Until 2024, the Appellate Division had 8 judges, compared to 101 judges in the High Court Division.

As of last year, the Appellate Division had 3,386 appeals pending, including civil, criminal, and jail appeals, along with 6,833 miscellaneous petitions such as civil and criminal miscellaneous, and contempt petitions. In addition, 20,901 petitions-civil, criminal, review, and jail petitions-remained pending during the period.

In the High Court Division, the volume of cases is significantly higher. Between 2015 and 2024, as many as 849,468 new cases were filed, while 555,332 were disposed of, leaving 589,651 pending by the end of 2024. As of 2024, the pending cases included 354,981 criminal cases, 115,212 writ petitions, 98,619 civil cases, and 20,839 original cases.

Following last year's July Revolution, the interim government established a series of reform commissions - among them, a Judicial Reform Commission tasked with overhauling the justice system.

The eight-member Judiciary Reform Commission was formed on October 3 last year with former Appellate Division judge Justice Shah Abu Nayeem Mominur Rahman as its chief.

The panel observed that to reduce the existing backlog and prevent future case congestion, the judiciary would require both long-term and short-term structural reforms. It put forward 15 long-term and 4 short-term proposals aimed at improving efficiency, capacity, and overall management of the justice-delivery system.

Among the long-term recommendations, several measures suggest ensuring the institutional independence of the Supreme Court, setting up a commission to promote transparency, merit, and credibility in the appointment of Supreme Court judges, overhauling the existing system for recruitment, promotion, transfer, and discipline of subordinate -court judges, and creating a permanent attorney service to bring greater efficiency and dynamism in the judicial process.

The commission also has recommended gradually increasing the number of judges in the lower courts to around 6,000, strengthening institutional independence, and deploying retired judges on a contractual basis in high-burden districts.

It has observed that "considering the number of cases and the country's population, it would not be possible to bring the case backlog to a tolerable level unless the number of judges in Bangladesh is at least doubled".

Recruiting 4,000 additional judges at once would be time-consuming, and newly appointed judges would lack sufficient experience. Therefore, the export panel suggests a gradual increase in the number of judges, maintaining a ratio of one judge for every 1,000 cases.

As part of its short-term recommendations, the Commission suggests appointing honest, competent, and physically fit retired District Judges on a contractual basis for two to three years in districts burdened with a high volume of pending cases-particularly criminal and civil appeals and revisions.

Such contractual judges should be deployed in districts where at least 1,000 appeals or revisions are awaiting disposal, to dilute the backlog and ease pressure on the existing judicial workforce.

And alongside increasing the number of judges, the government "must urgently ensure the necessary infrastructure, manpower, and logistical support to make the justice-delivery system more efficient".

Chief Justice Syed Refaat Ahmed, in the annual report 2024, said, "We have also taken care to provide a statistical overview of our work. The data on case disposals, pendency, and procedural innovations offer a transparent picture of our strengths and continuing challenges."

He added, "But these numbers do not end in themselves. Rather, they are vital tools of accountability and barometers of procedural justice. They speak of the efficiency of our courts, the workload of our judges, and our responsiveness to the justice -seekers."

Also, said the Chief Justice, "As a part of the reform initiative, we have pursued the institutionalisation of judicial independence through structural and policy measures."

The impact of case delays is felt deeply by ordinary litigants who have to roam around court premises and spend a price, too, in some instances of what pass for 'harassment cades'.

Abu Bakar Siddique, a businessman from far-flung northern Panchagarh district, filed a civil revision with the High Court in 2012 seeking the cancellation of a deed. Yet, after more than 13 years having elapsed, the case remains stuck in the hearing stage. It first appeared on the court's cause list in 2017, but no hearing did take place so far. Siddique, visibly disheartened, says, "I have been waiting for justice for over a decade, but it feels like my hopes have been crushed. I am completely fed up and have lost all faith in the system."

His lawyer, Barrister Mahmud Al Mamun Himu, who also practises in the Supreme Court, expressed deep frustration at the slow pace of the judiciary. "It has become almost impossible to bring the case to a conclusion," he told The Financial Express writer.

Himu added that he had filed other cases with the High Court back in 2003, which, like this one, are still pending. The prolonged delays, he laments, highlight the agonizing wait that countless litigants endure in pursuit of justice. Quazi Mahfujul Hoque Supan, Associate Professor at the Department of Law of a university and a former member of the Judicial Reform Commission, says judicial reform is a "long and extensive process" that cannot be achieved overnight.

sajibur@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.