Published :

Updated :

Intermittent mild earthquakes shaking parts of Chattogram and Dhaka about one-and-half decades ago must be fresh in the memory of many. Bangladesh, the eastern part of Bengal, hasn't experienced any major earthquake in the last one-and-half centuries. It's said that a major earthquake strikes a vulnerable swathe every one hundred years. The last temblor to hit parts of Bangladesh comprised tremors from domino effect of the Great Assam Earthquake of 1897. One hundred and twenty-four years have passed from that catastrophic quake, measuring 8+ on the Richter scale. It means the greater Bengal, especially the northeastern part of Bangladesh, has been long overdue for a brush with a major regional earthquake or its aftershocks. This time, it may not be the ripples coming from a great earthquake. Who can say for sure that the mostly unpredictable natural calamity of the future in Bangladesh won't be a disastrous one?

The repeated tremors that jolted the Sylhet city in the recent days have been termed countdowns to a great calamity. Seismologists have long singled out the Sylhet region as being a quake-vulnerable zone. The northeastern district, bordering Assam, has been experiencing occasional tremors in the last couple of decades. Those jolts have prompted the seismologists to reach the alarming conclusion: the Sylhet district, sitting on the active Dauki Fault, might be in for a major earthquake.

The mild tremors and their aftershocks which shook the Sylhet city saw a number of multi-storey buildings tilt sideways. A total of six seemingly vulnerable shopping complexes have been identified in the city by the Sylhet City Corporation as risk-prone. They have been declared shut for 10 days from May 31 to June 9. Sometime back, residents living in over 20 buildings had been asked to vacate the structures immediately. They have yet to comply with the authorities' directive. After the last week's repeated tremors, panic has evidently gripped many of the city's residents. Young volunteers have for a pretty long time been found engaged in regular earthquake drills. Those were aimed at training people on how to come out of a place where they are trapped; or ways to rush for the emergency exits, remaining far from tall walls or buildings. Most importantly, people would be reminded again and again of the imperative of switching off their electrical and gas lines before leaving their places.

All this is a laudable step. To the dismay of the cautious segments of the Sylhet city's residents, these drill organisers nowadays are seen lacking their earlier enthusiasm. Perhaps they have lately started believing that there is no imminent threat of an earthquake in the city and the suburbs.

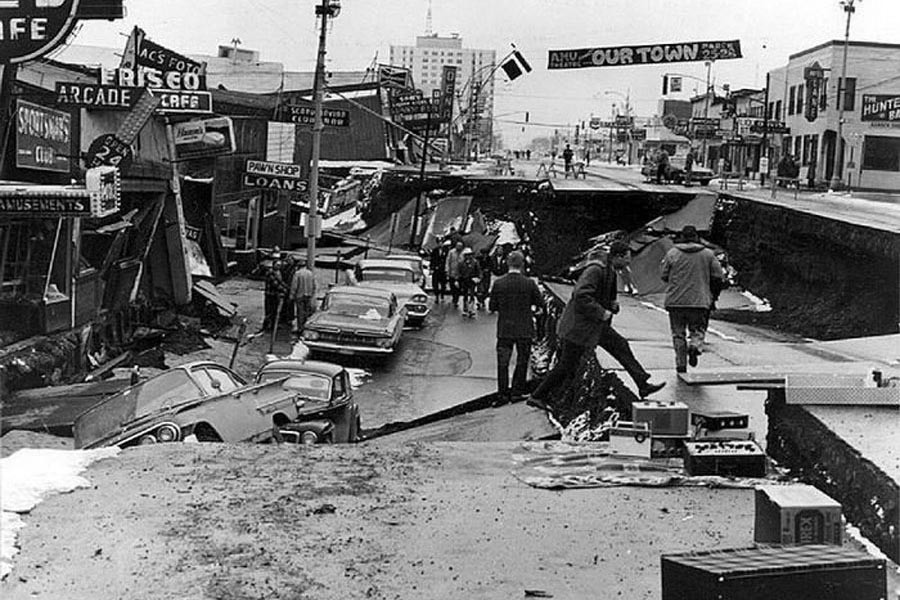

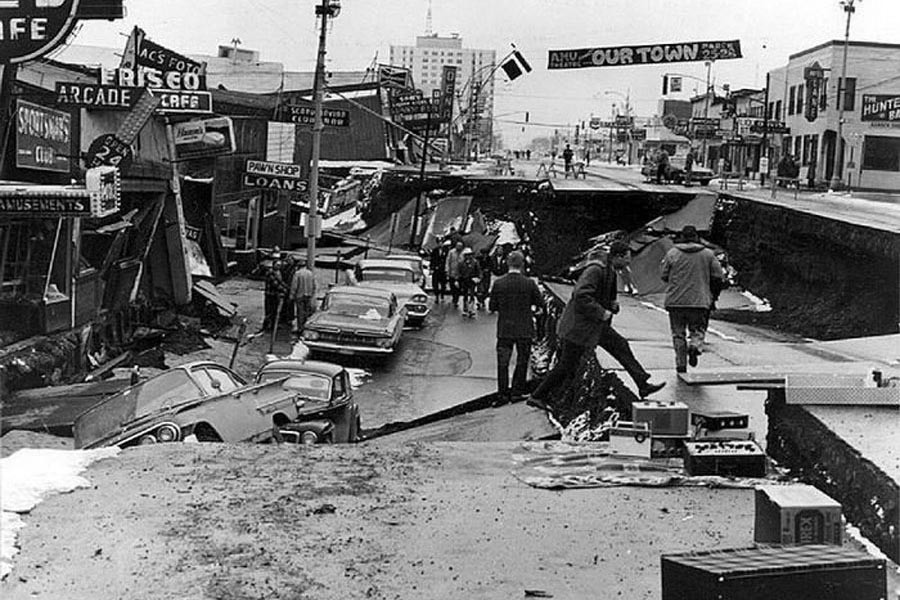

To repeat, earthquakes are the most unpredictable of the natural calamities. Before their final strikes, they have little signs. The continuous mild tremors on most of the occasions emerge as false alarms. Before the final strike at any time of the day or night, there might be few or no signals. In most cases, calamitous quakes have caught vast localities unawares. This results in greater volumes of destruction and fatalities than seen in cyclones and volcanic eruptions. The disasters of cyclone let their approach known by mid-sea depressions, turbulent seas, high winds that may continue for days. Before a volcanic mountain begins eruption, rumbling sounds underground and spewing out of light to dark smoke through the crevices of a mountain function as forecasts of the coming danger. Earthquakes in general show none of these warnings. This absence of warnings does, in no way, belittle the need for preparedness.

In a place plagued by dearth of infrastructural supports and populated by ignorant people, the preparedness remains lackadaisical. It later proves suicidal. To speak in brief, a foolproof preparedness and the skill in coping with emergencies can save lives and properties manifold compared to a state filled with bewilderment and confusions.

The situation in the Bangladesh cities --- Sylhet, Chattogram and Dhaka in particular, is dismal. Apart from the one in Tangail, not far from Dhaka, the Bangladesh capital sits on a fault line called the Sagain Fault. It is one of the major active faults in Myanmar. Chattogram lies within the range of the Mizoram-Tripura-Chittagong Folded Belt. Both the cities of Dhaka and Chattogram are vulnerable to major earthquakes. Sylhet sits on the Dauki Fault Line. It stretches from south of the Shillong Plateau, the highland region in eastern Meghalaya state of northeastern India, to the northern border of Mymensingh and Sylhet divisions. Dauki Fault has a length of 300 kilometres. Bangladesh is considered one of the most tectonically active regions in the world. It is situated where three tectonic plates meet. They are the Indian Plate, the Eurasian Plate and the Burmese Plate. The Indian Plate continues to move northeast, slowly colliding with the Eurasian Plate. The latest major earthquake jolting the vast tectonically active zone is the one that ravaged Nepal in April, 2015. It recorded 7.8 on Richter scale. The overall calamitous impact was, however, preceded by Gujarat's 7.7 Bhuj Earthquake in January, 2001. Four years later, a 7.6-magnitude temblor shook the Pakistani-administered Kashmir in October, 2005.

Coming to Sylhet in Bangladesh, except the distant impacts of the 1897 Great Assam Earthquake, the northeastern Srihotto, earlier name of the region, hasn't experienced any earthquake in the preceding centuries. But the recurring tremors over the couple of decades prompt a section of seismologists to keep in mind a vital fact. They believe the tectonic plates keep changing courses, prompting a 'new zone' to go through an earthquake. Other schools, however, do not subscribe to this theory. Notwithstanding the conflicting theories, many do not want to exclude Sylhet from the quake-prone regions in Bangladesh.

Sylhet is no longer a hillock-filled, lush green tranquil town of the past. It's now a divisional headquarters filled with multi-storey office buildings, apartments, shopping complexes, hotels etc. The city's population is on continued rise. Parts of the present Sylhet can be compared with some areas of the capital Dhaka. What's most distressing, even weeks back Sylhet used to be considered among the worst corona afflicted cities in Bangladesh. The cities also included Dhaka and Chattogram. With the spike in Covid-19 caseload and fatalities this year, few could be a worse time for an earthquake to strike this city.

If a high-intensity quake does strike the Sylhet city, the trail of devastation would be almost similar to that of Dhaka. Because of the capital's large and fast-expanding size, the stiflingly dense population, unplanned and ill-planned growth, weak utility infrastructure, lack of coordination among different service agencies etc, the spectacle of a post-earthquake Dhaka sends shudders down the spine. The horror and dreadfulness of the scenarios in big cities like Dhaka and Chattogram is set to be compounded by the invasion of the ongoing pandemic.

As the country is prone to natural disasters like cyclones and flood, it boasts of its vast disaster preparedness programme. It is alleged to be hamstrung by inadequacy of resources like skilled manpower, and proper planning and mechanism. This results in the lengthening of the avoidable sufferings of the disaster victims. As earthquakes cannot be predicted accurately, a large segment of the preparedness should be transformed into alleviating sufferings and miseries the nation may have to face up to. The country, apparently, can ill afford to deal with the double whammy of an earthquake and the raging pandemic. The need of the hour is coordination between different agencies like those dealing with disasters, public health, emergency supplies and law and order.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.