Published :

Updated :

The conspirators were so sure that Mushtaque would agree to be on board that no effort was made to contact him until a few days before the coup attempt. Khondakar Mushtaque and Khondakar Rashid shared the same family name. Khondakars are descendants of peers, that is, holy men and they came from neighbouring villages in Comilla. There was an advantage in approaching Mushtaque at such a late hour. The smaller the number of conspirators at the planning stage, the better are the chances of preventing any leak. The intelligence services in Dhaka, both civil and military, continued to remain in the dark.

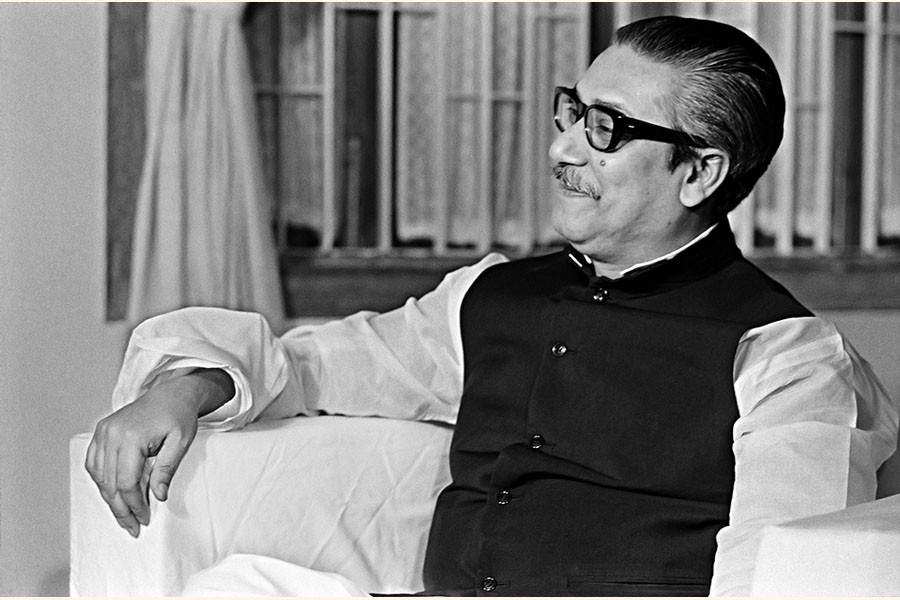

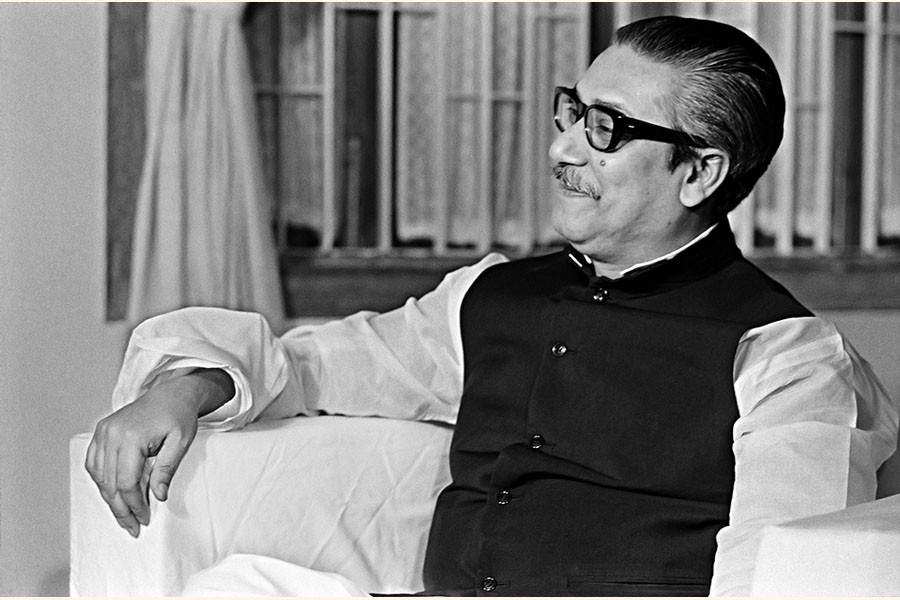

Meanwhile there was no doubt in Indira Gandhi's mind that conspirators were busy planning the overthrow of Mujib; it was merely a question of who exactly they were and when they would strike. In late April 1975 when both she and Mujib were in Kingston, Jamaica, for the Commonwealth Conference, she informed Mujib that "something was happening in Bangladesh." Mujib said: "What is your proof ?" "I (Indira Gandhi) could only say; please be careful. I think something terrible is going to happen." "No, no," he said. "They're all my children."

Despite Mujib's first impulse to reject any suggestion that any Bengali would raise his hand to strike him down, he appears to have had a delayed reaction. About a fortnight later, on Wednesday 14 May, Rahim made this entry in his diary: "Yesterday as soon as Bangabandhu stepped into his office he complained rather angrily about laxity of arrangements for his personal security and in Bangabhaban. Everything must be done to improve the situation in this respect." And Rahim added his own comment: "Actually there are many faults in the security arrangements. The main reason is that it is impossible to make comprehensive security arrangements in his present house. He refuses to go to reside in Bangabhaban or Gonobhaban."

In the following days several meetings were held to consider various ways of beefing up security for Mujib, but without any sense of urgency.

The two brothers-in-law Farook and Rashid concluded that the most convenient time and date for carrying out the coup d'etat would be in the early hours of 15 August. The armoured and artillery units under their commands would then be carrying out joint night exercise, routinely held every fortnight in a relatively deserted area north of the capital at Balurghat, the site of the present-day Zia International Airport. All they had to do was to convert their military exercise into actual operation by moving in the dead of night into the government quarters of the capital.

The time had now come for a face-to-face meeting with Mushtaque to win him over to their conspiracy. At 7 p.m. on 2 August Rashid went to see Mushtaque at his house. He had to be careful. Dressed in civilian clothes so as not to be easily recognised he took the precaution of carrying with him an application for a permit to buy a motor cycle to provide an excuse for meeting the Commerce Minister. Their meeting lasted almost two hours. Rashid had to find out how strongly Mushtaque felt about the current political situation. When it was clear that Mushtaque did not expect "progress under Mujib's leadership," Rashid felt bold enough to ask a direct question: "Will there be a justification at this stage if somebody takes a decision to remove Mujib by force?" Mushtaque answered: "Well, probably for the country's interest it is a good thing."

Now that Mushtaque was inclined in principle to support the objectives of the conspirators, further meetings were held between the two on the 11th, 13th and 14th. At these meetings they discussed how Mujib was "to be removed by force from the power and [that] it may lead to a killing of Sheikh Mujib," in Rashid's words. The actual date of the coup was not revealed to Mushtaque. So they were reassured to learn from Mushtaque that he had no plans to go outside Dhaka in the immediate future. He would be sorely needed to form a government after the coup.

It was also Rashid's idea to recruit ex-Army officers who had been forced to retire after the Dalim incident of the previous year. Dalim was contacted on the 13th. He was willing to join the plot. Dalim, on his part, brought in two retired Majors to the side of conspirators -- Noor and Shahriar.

These three retired majors were asked to come to the exercise ground at 10:30 p.m. on the evening of Thursday, 14 August to be briefed for the operation due to commence that very night. They arrived half an hour late but they brought with them two new initiates: Retired Major Pasha and Major Huda, a serving officer who happened to be a friend of Dalim.

Rashid took them to the tank garage where Farook, bent over a table-top, was examining a tourist map of Dhaka and its environs. Farook explained to them broad features of the operation and asked them whether they would volunteer to join. Unanimously, they replied in the affirmative.

The conspirators, all of them holding grudge against Mujib for one reason or another, were now like a coiled spring, ready to pounce on their assigned targets: Sheikh Mujib, Serniabat and Sheikh Moni. The most difficult task was the neutralisation of the Rakkhi Bahini in their barracks in Sher-e-Bangla Nagar in Dhaka itself. It was reserved for Farook himself.

At around the same time Sheikh Moni was in Mujib's house where the two of them remained closeted in the bedroom for a long time, with no premonition of the mortal danger they would have to face within hours. We will never know what they talked about. Was it about the "historic and unforgettable" reception that had been planned to honour Mujib in the University of Dhaka the next day? This may well have been the case, for we know that Mujib had been troubled by three grenade explosions shortly before noon that day in the vicinity of the university. No one had been killed or injured but there had been considerable material damage.

Naturally there were suspicions that the purpose of the perpetrators, thought to be leftist extremists, was to mar the celebrations. Mujib was so dissatisfied with the security arrangements of the police that in the afternoon he sent for Colonel (later Major General) Sabihuddin, the acting chief of the Rakkhi Bahini, Nuruzzaman having gone abroad to attend a short course in the United States, only a few days ago. Even Sabihuddin had gone to Bogra.

Security of Mujib's residence at this time was provided by a hotchpotch of three diverse groups. First, within the house itself there were a handful of men under Mujib's long-time personal bodyguard, Mohiuddin, stationed on the ground floor and the veranda. Then there were a few policemen with handguns inside the compound. Finally, there was a third ring of soldiers from the regular army. They were the only guards capable of offering serious resistance against plotters equipped with heavy weapons. Until the 2nd of August this group was manned by Lancers. Then they were replaced by soldiers from the 1st. Field Artillery based in Comilla. Farook had no authority over them. However some of the plotters like Huda had been officers of this unit before being forcibly retired. An accomplice was found among them, one Subedar Major by the name of Abdul Wahab Jowardar. Before midnight he asked them to hand over their ammunition to him in exchange for new ammunition to be issued to them shortly. Accustomed to obeying orders, they complied. Thus they were deprived of the means to protect Mujib and his household when the assault took place shortly thereafter.

Roughly an hour later that night the strike teams proceeded to their appointed target areas. Farook's tank column was in the lead. They had to go past the Cantonment check post, but the sentries failed to ask them why they were moving into the city limits without special permission. Farook's primary task was to neutralise the 3500 Rakkhi Bahini men in their barracks located halfway between the Cantonment and Mujib's residence.

Most of his tanks had dropped out for one reason or the other by the time he arrived at the Rakkhi Bahini garrison. Furthermore, Farook had no ammunition for his tanks. But he was able to bluff the Rakkhi Bahini arrayed in front of their barracks into believing that they were hopelessly outgunned and must submit to his authority. Leaving a tank to guard them, after they agreed to his conditions, he moved ahead towards Mujib's house.

Other strike forces proceeded by way of Mohakhali to their destinations: Serniabat's house on Minto Road and the Radio station close by. The first house to be attacked was that of Serniabat. He managed to telephone Mujib to warn him that armed miscreants were attacking his house. Realising the gravity of the situation Mujib hurriedly telephoned the duty officers downstairs to put him in touch with the Police Superintendent Mahboob in charge of the Special Police Force, numbering 600 men. Because of the lateness of the hour, the call was made to his residence. The telephone was in the room, while he was downstairs in the drawing room, discussing arrangements of the forthcoming marriage of his niece, with some relatives. So the call remained unanswered. Impatiently Mujib came down to enquire. It was at this point that the first shots were fired in the direction of the house. Some windows were shattered and one bullet hit the security officer standing beside Mujib. He tried to give him first-aid but when he saw that the wound was not serious he rushed back to his bedroom to telephone Shafiullah and some others on the direct line to ask for help. Shafiullah and the Dhaka Brigade Commander Colonel Shafat Jamil had been trying to piece together over the telephone fragmentary reports about the movements of some units without authorisation out of the cantonment just before Mujib's call came through. Shafiullah said, "We are doing something" and begged Mujib to get out of the house if he could.

Meanwhile Kamal, having heard the gunfire, got dressed up in a hurry and came downstairs. By this time security guards from inside the compound had fired back at the attackers, killing one and severely wounding two others. Enraged attackers, led by Majors Huda, Noor and Mohiuddin then opened up with all their weapons and forced their way into the house. When Kamal saw the black-uniformed Lancers he assumed that they were reinforcements sent from the Army headquarters. As Kamal identified himself and welcomed them, he was gunned down instantly. The killers then went on a rampage and shot dead every member of the family: Mujib and his wife, their three sons, two newly-married daughters-in-law, and his brother Nasser. Mujib himself was killed at the turn of the stairs as he asked them, "What do you want?" The only members of the Mujib family to escape death were Mujib's two daughters -- Hasina and Rehana who happened to be away in Europe.

In Serniabat's house he and several members of the household were killed as well as a house guest. Hasnat, Serniabat's son, managed to escape by hiding in the loft near the roof, while some of his children were killed in the drawing room. At Sheikh Moni's house both he and his wife were shot. They did not die on the spot but were so critically injured that they expired shortly after being taken to the Medical College Hospital. The dead and injured members of the Serniabat household were bought to the hospital around the same time. A little while later injured servants from the residence of Mujib also arrived at the hospital. They told harrowing tales of how each and every member of the Mujib family had been hunted down and killed. The news of the carnage spread rapidly in the neighbourhood.

Thousands of people started to converge on the hospital and demanded that the dead bodies be handed over to them. They wanted to carry them in a procession through the streets of Dhaka as a mark of mourning before their funeral. This may well have led to the turn of the tide against the plotters by creating a surge of sympathy for the Mujib family and revulsion against their brutal killers. But the moment was not seized because none of the front leaders of the ruling party was there to exploit the situation. Where were they? We know something about the movement of at least one leader: Tofael Ahmed. He had shown considerable ability to mobilise a movement for the release of Mujib during 1969. But he was cowering in his home when his skills as an agitator were most needed to turn private grief of thousands of ordinary people into public fury.

Fortune, it is said, only smiles on the brave. On this day it was the young plotters who acted with boldness and determination with less than five hundred men at their disposal. They sent troops to the scene before the number of demonstrators could swell and become unmanageable. Leaderless, the crowd melted away. Corpses could now be safely consigned to the morgue out of sight of the general public.

The service chiefs were then rounded up by Dalim and his men and escorted to meet Mushtaque. He greeted Shafiullah affably with these words: "Congratulations. Your troops have done an excellent job. Now do the rest." Shafiullah asked, "What rest?" and received this answer: "You should know it better."

Identically-worded statements were handed to them, as well as to the acting chief of the Rakkhi Bahini and the Inspector General of Police to announce over the radio their pledge of allegiance to the new government and they did as they were told.

Martial Law had earlier been proclaimed and curfew imposed for an indefinite period. But as the 15th happened to be Friday the curfew had to be lifted for an hour and a half to allow people to go the mosque to offer their Jumma prayers. Many must have prayed for Mujib's soul, for he was personally well-liked even by a large number of those who disagreed with his policies and thought he was no longer the right man to lead the country. Mushtaque and the young rebel officers had been nervous whether this window of opportunity would be used by the party leaders to try to rally the party faithful, but nothing happened. The party hierarchy, or what was left of it, were too confused and demoralised even to consult among themselves as to what should be done. By their inaction, they accepted the fait accompli.

The conspirators took full advantage of the confusion in the leadership and the ranks of the ruling party. As soon as the Jumma prayers were over they sent out jeep-loads of armed men along with an emissary to invite a number of Cabinet Ministers of the Mujib regime to join the new government, excluding of course those who were considered to be the inner circle of Mujib. Some agreed to join out of fear for their lives, some probably because they thought they could bring a moderating influence in the new government. Among them were two Hindus, Monoranjan Dhar and Phani Bhushan Mazumder. No doubt there were some among them who were happy to be able to retain their ministerial jobs in the post-Mujib regime. Mushtaque was thus in a position to announce the names of his Council of Ministers that very afternoon. There were eleven of them, all civilians. The formation of an all-civilian government headed by a very senior Awami Leaguer and containing some of the well-known figures of the previous government gave a false appearance of continuity and made it easier for the people to reconcile themselves to the new regime.

A little while later Mushtaque was sworn in as President of the People's Republic of Bangladesh in a simple ceremony attended by the service chiefs and high military and civil officials. In their first broadcasts the rebel officers had announced a change of the name of the country to Islamic Republic of Bangladesh. Mushtaque disregarded this designation because he was intelligent enough to realise that to take his oath of office under a designation other than the People's Republic of Bangladesh would introduce a jarring note of discontinuity which would not only be internally divisive but make it difficult for the new regime to get speedy recognition by the international community. Within days Mushtaque's government would be recognised by all countries of the world, Pakistan being the first and India the last.

In the evening Mushtaque addressed the nation. He said that he had to take over as President "for the historic need of the country" and praised the "patriotic armed forces [who] have come forward heroically for the success of the step."

As Mushtaque spoke, corpses of Mujib and his family members lay scattered all over the house. Just before dawn of the following day, the 16th, all of the bodies, except one, were collected by a special detachment of the Supply Battalion and transported to the Banani Cemetery for burial in unmarked graves. The exception was that of Mujib's body because the new rulers did not want to take the risk of his burial site becoming a place of pilgrimage. It was therefore decided that he would be buried at his native village of Tungipara in the family graveyard far from the teeming masses of Dhaka.

On the next day at 1 p.m. Brigadier Abdur Rauf, the Director General of Forces Intelligence (DGFI), held a meeting of his officers to brief them about the decision to take Mujib's mortal remains to Tungipara for burial. He asked for a volunteer for this task. No one volunteered. So the DGFI ordered his adjutant, Major Haider Ali, to perform this responsibility. He was told that the local officials had already been alerted. All he would have to do was to hand over the body to an adult male relative and supervise the burial. 14 soldiers would accompany him for security purpose. At the helipad the pilot warned the Major that the job should be completed within two hours since it was dangerous to fly the helicopter after nightfall. When it landed at Tungipara the village had a deserted appearance. There were no males to be seen anywhere. The last time they had seen the military in strength was in the spring of 1971 when Pakistani troops had come on a mission to burn down Mujib's ancestral home and terrorise the local population. Probably they expected a repetition of their 1971 experience and did not want to take a chance. After a short search they found an old man by the name of Mosharraf Hossain who happened to be distantly related to Mujib. After the lid of the coffin was lifted he formally identified the body as that of Mujib and it was officially handed over to him. Meanwhile, a number of people ventured out of their hiding places and appeared on the scene.

The Major was anxious to get over with the burial of Mujib without delay. He asked the local police officer to fetch the imam of the village mosque. When he arrived the Major told him to bury the corpse immediately. The imam of course knew by then whose corpse it was and he asked a simple question: "Is this a corpse of a Muslim? If so, it can only be buried after a purifying bath and janaza (the final funeral rites)" The military officer firmly told him to forget about these niceties and go ahead with the burial. The imam conceded that an exception could be made in the case of a Shahid (Martyr): "Is he then a Shahid?" The military officer understood the significance of the loaded question, for a Shahid is a Muslim who has died fighting for his belief and is buried unwashed so that his wounds should testify to his martyrdom on the Day of Judgment.

The Major therefore relented but insisted that the burial rites be performed expeditiously. So, a bucket from a cow-shed next door had to be used to fetch water from a tubewell for the purifying bath. The only soap that was available for this purpose in the village store was a cheap laundry soap. There was no clean white cloth to be found anywhere in this village. The local police officer suggested that some saris donated by Mujib to a nearby Red Cross hospital could be used for his shroud. "We have no objection. You can bring anything you like. But you are to complete the bloody burial business quickly," the Major answered in military English in which every sentence is liberally sprinkled with the all-purpose word "bloody." Three saris were procured from the hospital. Their red borders were trimmed with a razor blade to make a makeshift white shroud. There was no time to stitch the pieces together. There followed a hurried janaza, in which some 25 people took part. Mujib's body was then lowered to the grave beside that of his father. The Major and his military escort were able to fly out well before dusk so as to arrive safely in Dhaka before nightfall.

Thus ended the life of Sheikh Mujib -- the man who was the Father of the Nation.

The piece is excerpted from the Chapter-57 titled 'The End of the Mijib Regime' in the book named 'Sheikh Mujib: Triumph and Tragedy' written by S A Karim (University Press Limited, Dhaka, 2020)

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.