Published :

Updated :

"There goes the Meghna Express power," says Anik Bal, pointing at the blue-yellow locomotive slowly moving away.

Standing at a safe distance from the tracks, I notice the locomotive number - 2938. Built by South Korea's Hyundai Rotem, it is a 1,500-horsepower engine with a top speed of 107 kilometres per hour. In its early years, it pulled major intercity trains, including Subarna Express and Lalmoni Express.

"The locomotive faced several accidents, including a fatal one that killed an assistant locomotive master (ALM) named Nur Alam Sharif in 2017. It underwent repairs at the Central Locomotive Workshop in Parbatipur, but could not regain its glory," says Anik.

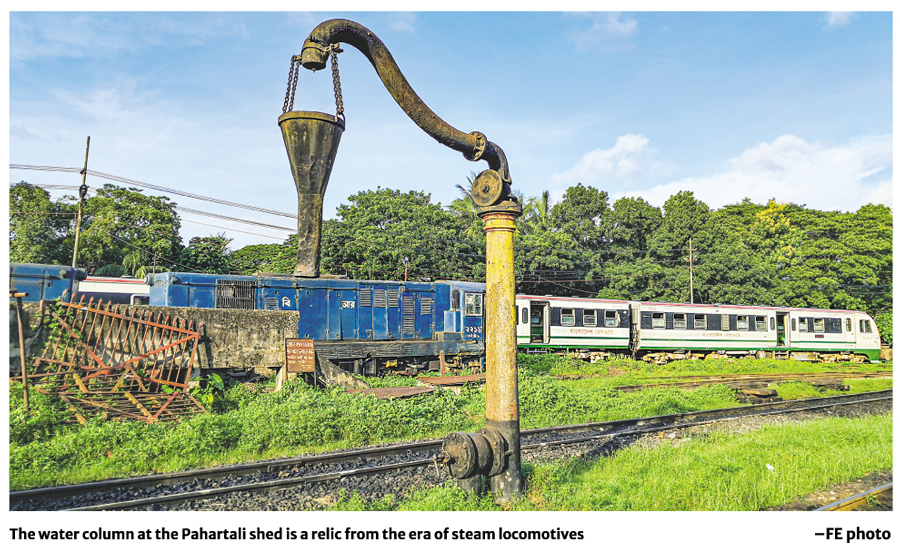

It is a warm and humid July afternoon, and we are at the Pahartali locomotive shed in Chattogram. Located across the Pahartali railway station, behind a weathered red wall with dark patches, it is partially visible to train passengers. Built during the British era, it houses locomotives, as well as handles small repairs and regular maintenance.

"Simply put, a locomotive shed is the home of engines. Before and after a journey, a locomotive stays in the shed. It does not always remain attached to the rake," explains Anik, an ALM under the Pahartali shed, while giving me a tour of the crucial facility in Bangladesh Railway's east zone.

The Pahartali station's rusty red footbridge offers a wide view of the shed. Standing under the bridge, I see multiple sets of tracks that create a network of internal lines and lead to the main shed. A group of boys hang out on the tracks, and two others lean down to pick up ballast.

Nearby, discarded wooden sleepers are piled up on the grassy ground. Next to some yellow wagons, a relief train with bright red carriages and silver windows stands ready to be called in. A small tin-roofed room beside the relief train looks like an isolated cabin in the large open area.

Further ahead, next to an unused diesel electric multiple unit (DEMU) train, old locomotives, including 2204, 2221, and 2025, stand idle. Their weathered, faded blue bodies give them a vintage look and also bear signs of neglect. I touch the 2025 locomotive and try to feel a connection to the bygone era when it ruled the tracks.

"Built by Canada's General Motors Diesel, the 2025 locomotive arrived in 1954. Even after 70 years, the 1,125-horsepower engine sometimes hauls freight cars, though it powered important passenger trains like Ulka Express and Mahanagar Express in its prime. Due to old age and lack of maintenance, it often breaks down," Anik says.

A pungent smell of oil and machinery fills the air as we step into the massive shed after walking past a water treatment plant. Supported by tall, rectangular columns in the middle, the sloped ceiling is made of corrugated tin sheets and meets a groundscraper on each side. Translucent panels at regular intervals allow natural light inside.

Several modern blue-yellow locomotives, mostly of class 3000, are parked on parallel tracks separated by ramps, which are coated with grime. The tracks run above inspection pits that allow workers to access the underside of locomotives. We take a narrow, earthen path to reach the other side of the shed.

Oil drums, mostly red, and fire extinguishers lie on the path, which runs along the beige wall of one of the groundscrapers. Rectangular nameplates, including that of the sub-assistant engineer of the loco running office, are attached to the wall. Green, Z-bracing wooden doors provide access to several facilities, including the general store, the general tool room, and the consumable oil store.

"Nearly 150-200 people work at the shed, which is open round the clock. The divisional mechanical engineer (loco), Chattogram, is the chief," says Anik, who hails from Chattogram and has a bachelor's degree in electrical and electronics engineering from the University of Science and Technology Chittagong.

Big trees with dense foliage, along with grass and small plants, dominate the backyard, where I find more locomotives with rusty exteriors and broken parts, including 2202. One of them is heavily deformed and decayed, with the skeletal frame exposed. Sunlight peers through the foliage, casting a soft light on the silent engines and the green surroundings.

Flanked by disused DEMU trains on both sides, a thick-trunked tree, possibly a sacred fig, stands prominently, its fallen leaves scattered on the ground. Squeezing through the semi-open door, I enter a DEMU carriage and see the sorry state inside. Thick layers of dust cover the faded green benches and the grey floor, which is littered with rubbish, including dead leaves and torn cardboard boxes, while cobwebs hang here and there on the discoloured walls and window edges.

DEMU trains were once part of a plan to introduce smarter daily commuting, but now they decay at the shed. Behind them, tracks continue under dense canopies towards a gated area, with green vegetation visible till the furthest point. I take a picture, where the horizon looks like the gateway to a forest.

With several railway buildings on both sides, including an oil control laboratory, we retrace our steps to the shed and walk up a ramp to get a close-up view of a diesel locomotive that stands on an inspection pit. Several of its access doors are open, revealing an array of components, including starter motors and filters. Evenly spaced rectangular columns support the tracks on the pit, while the ground is stained by dark, oily patches.

The shed usually hums with the sounds of sophisticated tools, roaring locomotives, and regular upkeep, but is now rather quiet as no major work is underway. Anik briefly chats with a person, who appears to be working inside the 3006 locomotive. Stained pillars and walls display various warnings: "Smoking prohibited", "Save yourself", and "Do not litter the shed floor".

"Locomotives undergo extensive checks in the shed before and after every trip. Before a journey, a locomotive is checked twice. The first is an overall check, which includes examining oil and water levels, components, and undergear. In the undergear, the condition of traction motors and carbon brushes is checked, among others," says Anik.

"The locomotive master and the ALM, who will drive the train, carry out the second inspection to make sure the engine is ready to roll. If they detect any trouble, they inform the shedman and the maintenance team. The team then fixes it," he adds.

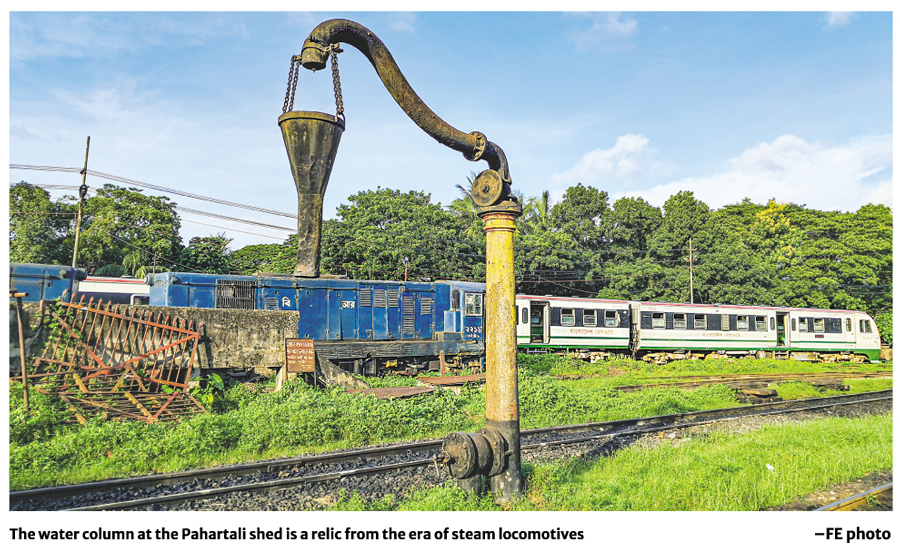

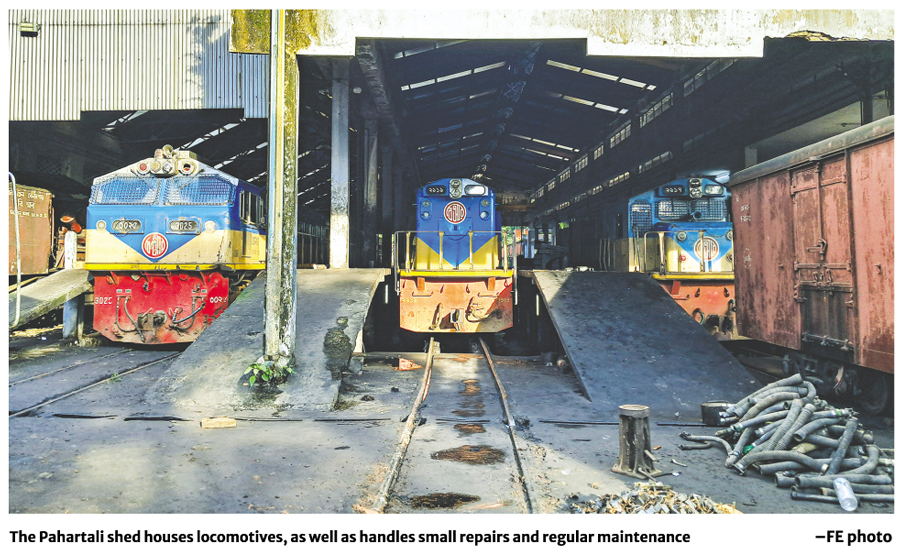

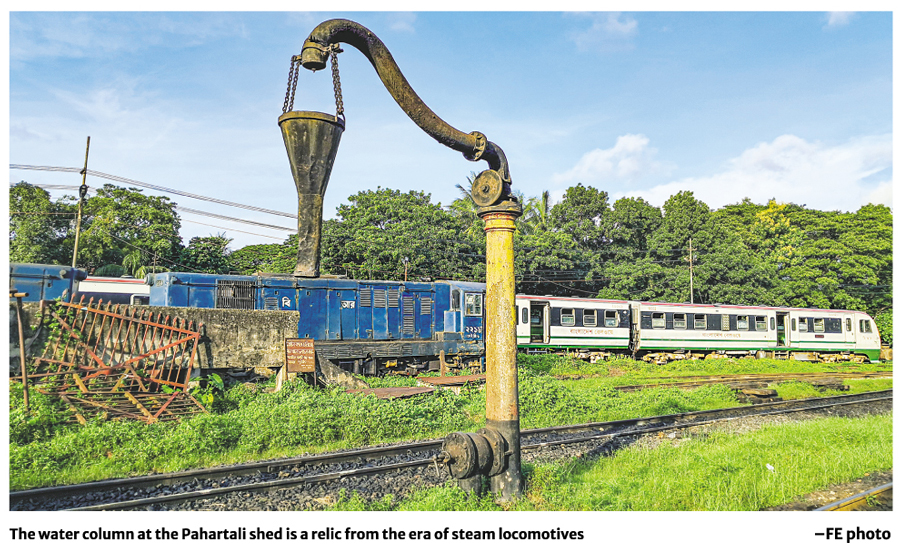

Going back to the front area, I see a steam-era water column, which has a faded yellow cylindrical base, a curved delivery pipe, and a large funnel. It was used to deliver large volumes of water into the tanks of steam engines. The water was essential for generating the steam that powered the locomotive.

Strolling down the driveway that leads to the shed's main entrance, I see some more locomotives, including 2721, 2712, and 2224. Just when the parade of these old iron giants is about to become monotonous, a vast and circular void on the ground near the entrance grabs my attention. I get closer and the grand turntable reveals itself, bathed in the yellow afternoon light under the blue sky.

A turntable is a specialised piece of equipment to rotate locomotives and was essential during the era of steam locomotives, which were not configured to run in both directions. It consists of a circular pit with a rotating bridge in the centre. The locomotive that needs to be turned is driven onto the bridge, which is then rotated using hand levers.

"ALMs, including me, operate the turntable. Moving the levers is of course tough, especially for those who are weak and sick. It gets tougher if the locomotive is not correctly placed on the bridge," says Anik.

Stepping outside the main entrance, I see a warning on the iron gate that says access to the area is limited. But the warning is symbolic only as people freely cross the unmanned gate. The central office of the Bangladesh Railway Running Staff and Sramik Karmachari Union is right next to the gate, and young boys play cricket in the forecourt.

Small tin-roofed stores, mostly selling snacks, line both sides of the uneven street that leads out of the shed and goes towards the historic Pritilata Square. Anik, who also plays the guitar and sings as a hobby, and I have some light refreshments at one of the shops. He is dressed in a white crew neck t-shirt with orange sleeves, blue jeans, and white sandals.

"How many locomotive sheds are there on the Dhaka-Chattogram route?" I ask.

"Four. Dhaka, Akhaura, Laksam, and Pahartali. I have been to all of them."

"Which one is your favourite?"

"Of course, Pahartali. I love this place."

r2000.gp@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.