From catalytic capital to catalytic capability A new policy-led strategy for Bangladesh

Published :

Updated :

As shrinking concessional capital exacerbates a long-standing credibility gap, Bangladesh must pair a robust, enforced Impact Measurement & Management (IMM) architecture with a strategic government role as a first-loss catalyst to unlock significant private commercial investment.

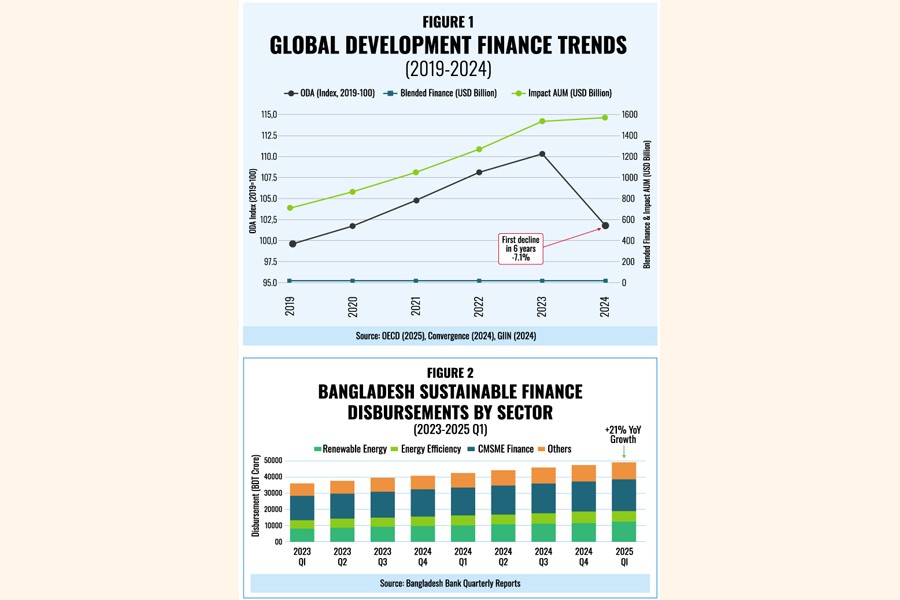

For decades, the architecture of development finance rested on a reliable cornerstone: a steady flow of official development assistance (ODA) from wealthy nations. This public money often played a catalytic role, absorbing the initial risks of investing in frontier markets and thereby ‘crowding in’ more cautious private capital. But that cornerstone is cracking. In 2024, for the first time in six years, global ODA fell in real terms, dropping by a sharp 7.1 per cent. This is not merely a funding crunch; it is a structural reset, with donor nations increasingly redirecting funds toward domestic interests and defense priorities with stronger bipartisan support at home. For countries like Bangladesh, this trend exacerbates a long-standing challenge: a lack of standardised and trusted impact data. While building a robust Impact Measurement and Management (IMM) system is a critical foundation, it is not a silver bullet. To truly unlock the next wave of private investment, Bangladesh must adopt a two-pronged strategy: pairing a credible, enforced data architecture with a new, proactive role for the government itself as a catalytic investor.

The New, More Discerning World of Capital

The decline in ODA is more than a headline figure; it reflects a profound shift in global priorities. As traditional donor governments look inward to bolster their own economies and communities, the pool of readily available, high-risk concessional capital is shrinking. This scarcity makes the remaining capital more selective. The blended finance market, which strategically combines public and commercial funds, held steady in 2024 with US$18 billion in deals, but the terms are hardening. Investors demand stronger evidence of impact and additionality before committing.

Simultaneously, the private impact investing market has swelled to an estimated US$1.57 trillion, according to the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN). This capital is not necessarily seeking subsidy, but it is starved for credible, verifiable data. The challenge of weak standardisation and comparability in impact reporting is not new, but the retreat of donor-funded de-risking has brought it into sharp relief. Without a trusted intermediary to absorb risk, private investors are left to price it themselves – a task made nearly impossible by fragmented and unverified impact claims.

Figure 1: Global Development Finance Trends (2019-2024)

Figure 1: Global Development Finance Trends (2019-2024)

Source: OECD (2025), Convergence (2024), GIIN (2024)

Bangladesh’s Pipeline vs. The Enforcement Gap

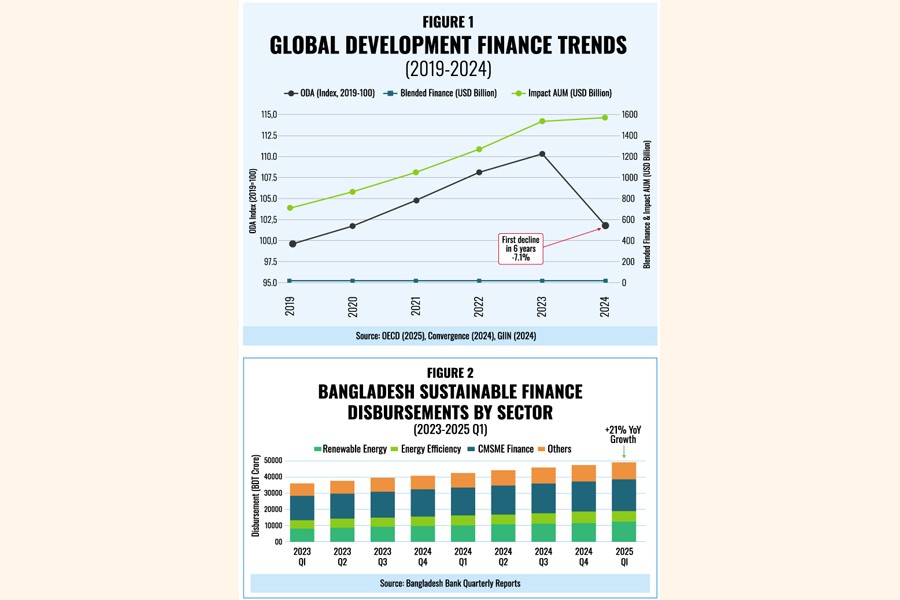

Bangladesh is not short on ambition or opportunity. The government’s Integrated Energy and Power Master Plan (IEPMP) targets 40 per cent clean energy by 2041, and a 2025 mandate for rooftop solar on public buildings creates a vast pipeline of bankable projects. The domestic financial sector is also mobilising, with sustainable finance disbursements growing 21 per cent year-on-year in early 2025, spurred by enabling policies from Bangladesh Bank and the Bangladesh Securities and Exchange Commission (BSEC).

Figure 2: Bangladesh Sustainable Finance Disbursements by Sector (2023-2025 Q1)

Source: Bangladesh Bank Quarterly Reports

However, this progress is hampered by a critical flaw: the absence of a powerful regulatory authority to enforce standards. While new rules for sustainable bonds and green lending are welcome, they are insufficient without a body that has the teeth to make foreign limited partners (LPs) and commercial investors feel secure. Market development, training and standardised IMM practices are essential, but without robust enforcement, they fail to build the deep, institutional trust required to attract capital at scale. This is not a credibility gap, but an enforcement gap.

Figure 3: Bangladesh Sustainable Finance Regulatory Timeline

Source: Bangladesh Bank, BSEC, Switch-Asia

A Two-Pronged Solution: State as Catalyst, Regulator as Gatekeeper and Enforcer

To navigate this new reality, Bangladesh must move beyond simply developing standards and actively build an architecture of trust backed by state power. This requires a dual strategy.

1. Building an Enforceable Impact Architecture

First, the country must establish a world-class IMM system with enforcement at its core. This involves creating a national IMM taxonomy aligned with global standards (IRIS+), fostering a local market for independent verifiers, and integrating mandatory, standardised impact reporting into all financial disclosures. Critically, this cannot be a voluntary exercise. A regulatory authority – whether a strengthened BSEC or a new, dedicated body – must be empowered to audit claims, penalise misreporting, and provide a level of oversight that gives foreign investors confidence. Without enforcement, standards are merely suggestions.

Figure 4: Impact Measurement & Management Funnel

Source: GIIN IRIS+ framework, adapted for Bangladesh context

2. The Government as a Catalytic Investor

Second, and more radically, the Government of Bangladesh should step into the role previously held by DFIs and donors: the provider of catalytic, first-loss capital. By creating a state-backed fund to absorb the initial risk tranche in key blended finance deals, the government can send the most powerful signal possible to the market. Knowing the sovereign has skin in the game and will absorb the first hit would dramatically de-risk projects for foreign commercial investors.

In high-income markets, governments pioneered catalytic “first-loss” tools—EU budget guarantees under EFSI/InvestEU and U.S. state loan-loss reserves—so private investors could take senior positions with de-risked exposure. That template is now migrating to middle-income countries: Indonesia’s SDG Indonesia One (via PT SMI) blends concessional first-loss with private debt; Nigeria’s InfraCredit uses sovereign-linked guarantees to mobilise pensions; Chile’s CORFO has long acted as a catalytic LP with downside protection in VC funds. For countries graduating from LDC status, this shift is essential: as grants and soft loans taper, a state-backed junior tranche signals policy commitment, lowers the cost of capital, crowds in foreign and domestic institutional money, and accelerates the SDG-aligned infrastructure and industrial upgrades needed for a durable, post-LDC growth path.

In high-income markets, governments pioneered catalytic “first-loss” tools—EU budget guarantees under EFSI/InvestEU and U.S. state loan-loss reserves—so private investors could take senior positions with de-risked exposure. That template is now migrating to middle-income countries: Indonesia’s SDG Indonesia One (via PT SMI) blends concessional first-loss with private debt; Nigeria’s InfraCredit uses sovereign-linked guarantees to mobilise pensions; Chile’s CORFO has long acted as a catalytic LP with downside protection in VC funds. For countries graduating from LDC status, this shift is essential: as grants and soft loans taper, a state-backed junior tranche signals policy commitment, lowers the cost of capital, crowds in foreign and domestic institutional money, and accelerates the SDG-aligned infrastructure and industrial upgrades needed for a durable, post-LDC growth path.

The leverage of this model is immense. The SDG Loan Fund, for example, saw a US$25 million first-loss tranche from the MacArthur Foundation unlock over US$1 billion in commercial capital from giants like Allianz and FMO—a 40x multiplier. For a new administration in Bangladesh, establishing a similar national catalytic fund would be a low-cost, high-impact ‘low-hanging win,’ immediately making its renewable energy and infrastructure pipelines vastly more attractive to global investors.

Figure 5: Capital Stack Comparison - Catalytic Tranche vs. IMM Assurance

Note: In the revised model (Stack A), the orange catalytic tranche would be provided by the Government of Bangladesh.

Source: Convergence blended finance definitions (conceptual)

Call to Action: A New Partnership for Growth

For Bangladesh, the path to a sustainable and self-reliant development model is clear. It involves a fundamental shift in how it engages with global capital—moving from a passive recipient of aid to an active, strategic co-investor. By pairing a rigorously enforced impact data regime with a state-led catalytic fund, the country can create a uniquely powerful value proposition.

While a state-backed first-loss fund could catalyse private investment, it also carries significant risks if poorly governed. Without strict safeguards, such facilities can become vehicles for politically motivated or failing projects – mirroring past inefficiencies seen in instruments like the IDEA Fund or Startup Bangladesh. Mispricing risk, opaque selection, or weak oversight could distort markets, burden the treasury, and erode investor confidence. To prevent this, Bangladesh must establish a robust Impact Measurement and Management (IMM) ecosystem – anchored in standardised metrics, independent verification, and transparent disclosure – to ensure that public capital truly drives measurable, sustainable outcomes. Done right, a catalytic fund can signal Bangladesh’s readiness to graduate from LDC status; done wrong, it risks becoming a fiscal liability disguised as development finance.

This new model replaces uncertain donor generosity with sovereign commitment. It tells the world that Bangladesh not only measures its impact but stands behind it. This is a task for the entire financial ecosystem, but it must be led by a government willing to use its balance sheet to catalyse growth and its regulatory power to guarantee trust. If concessional capital was yesterday’s catalyst, a strategic state is tomorrow’s. By making that pivot, Bangladesh can secure its sustainable development for decades to come.

The writer is a Partner at Inspira Advisory and Consulting Limited. He can be reached at salman@inspira-bd.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.