Published :

Updated :

Trains move on, but some journeys remain unfinished in the mind. In candid conversations with The Financial Express, four veteran locomotive masters of Bangladesh Railway recall moments of fear, bravery, and responsibility on the rails that still haunt them

One night in 2015, I was driving the Dhumketu Express from Rajshahi to Dhaka. It was around 3am, and the train was moving smoothly. Then, in the beam of the headlight, I saw a big stationary truck on the tracks.

It was somewhere between the Ibrahimabad [then Bangabandhu Bridge (East)] and Tangail stations, with trees and LC gates on both sides but no houses. I hit the brakes as soon as I noticed the truck, but it did not help because the vehicle was too close.

The train ploughed into it with a thud, hitting it right in the middle and smashing it into two parts.

The truck was loaded with Sylhet sand (reddish sand from Sylhet used in construction), which spilled all over the cab and the locomotive. The ALM and I did not get injured, but we were covered in sand. The train screeched to a halt a short distance away.

No passengers came out, probably because they were all asleep. Looking around, I did not see the trucker or anyone else. After informing the railway control office, I inspected the locomotive for damage, which was minor. A pipe broke, and the air reserve tank was slightly displaced, causing leakage.

Some 20 minutes later, I resumed the journey. It was not easy to sit in the cab and drive because of the sand, but I persevered and reached Joydebpur. The locomotive was changed there, and another LM drove the train to Dhaka. It was the only vehicular collision in my 41 years of service.

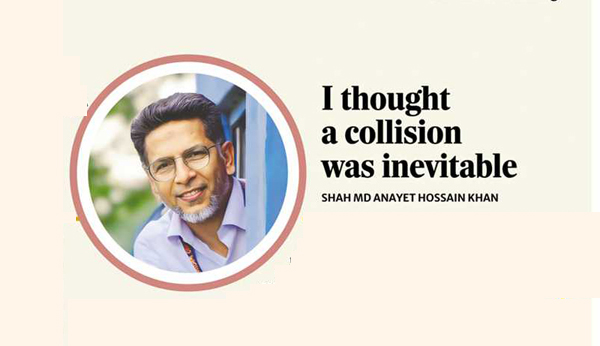

On February 21, 2025, I was at the controls of the Mymensingh Express, heading to Akhaura from Mymensingh. Shortly after the Jummah prayers, we passed Brahmanbaria. I was approaching an unmanned LC gate before the Titas Railway Bridge.

From about 300 yards away, I saw an autorickshaw crossing the LC gate. Its rear wheels suddenly jammed on the tracks. I throttled down and sounded the whistle continuously. One of the autorickshaw passengers got off and looked in the opposite direction, mistakenly thinking the train was coming from that side. Before I throttled down, the train was running at 50 kilometres per hour. As the distance between us narrowed to around 50 yards, the speed reduced to 35 kilometres per hour. But the autorickshaw was still stuck, and passengers were still inside.

That was when I applied full brakes. Both the ALM and I were yelling, desperately trying to get the attention of the passengers. But there was no response from them, while the driver kept trying to get the vehicle moving. For a moment, I thought a collision was inevitable. But with the blessing of the Almighty, it was a near miss. The train hissed to a halt within inches of the autorickshaw. All the passengers, except for one, had jumped off seconds before the train stopped. I saw the autorickshaw driver standing there, frozen and in tears, while others pushed the vehicle off the tracks.

It was sometime around 2016-17. I had just become an LM (grade 2) and was assigned to the second link (mail and local train routes). One winter afternoon, I was driving the Karnaphuli Express from Akhaura to Chattogram. The Dhaka-Chattogram route had not yet been upgraded to double lines.

Shortly after gliding out of Akhaura Junction, I spotted some children playing on the tracks ahead. They scattered at the sound of the whistle. But one little boy, probably two or three years old, stood still. He just stared at the oncoming train, perhaps thinking it would stop.

I hit the brakes when I realised he would not move, but it was too late already. The train ran over him and stopped. I hurriedly got out of the cab and pulled him out from underneath the train with the help of others. His small hands were partially severed, and the forehead was fractured. I wrapped his bleeding hands with my handkerchief. His parents arrived soon after and rushed him to a hospital.

A week later, I went back to the spot, which was in Debagram. Without revealing my identity, I asked around for information about the boy. Locals said he had survived, but his hands had to be amputated.

I felt a deep sense of relief. My wife had endured two miscarriages by then, and we were longing for a child, which was why the incident left an indelible mark on my mind. I still remember his face.

It was a November night in 2023.

I drove the Tangail Commuter train from Dhaka to Tangail, reaching there at 12:05am. While resting in the running room (a facility for train crew to rest at stations between duty shifts), I received a call from the station master at 2:50am. He urged me to come fast because a fire had broken out on the train. ALM Shiplo Kumar Roy and I rushed to the platform.

The fire, burning in the middle of the first carriage, right next to the locomotive, was spreading in both directions. Our first priority was to save the locomotive.

Thick smoke had already engulfed the scene, making it impossible to see the locomotive coupling clearly. Shiplo braved the smoke to search for the coupling, found it, and managed to detach the locomotive when it was about to catch fire.

I quickly drove the locomotive forward to a safe distance. Meanwhile, the fire was spreading in the opposite direction where the power car (a railway vehicle that supplies electricity to the entire train) was in the fourth position. I reversed the locomotive and drove it to the other side of the train.

Shiplo decoupled the power car from the third carriage and then coupled the last coach with the locomotive, enabling me to haul that set away. By the time the fire service arrived, two carriages had been burned.

I acted not only out of bravery but also my responsibility as a railwayman to protect the railway’s assets. I could have been burned if I had not acted right away. Had the locomotive caught fire, there could have been explosions with disastrous consequences.

r2000.gp@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.