Published :

Updated :

National elections critically influence economic growth and inflation across countries. Studies have examined patterns such as declining growth and rising inflation in election years. As Bangladesh prepares for the 13th parliamentary election on February 12, along with the referendum on the July Charter and related constitutional amendments, it may be worthwhile to explore the inflation-election correlation.

Some interesting observations come from studies on the inflation-election relationship, mostly by economists in developed countries. For example, right-wing incumbent governments usually fight inflation during election years. Left-wing incumbents focus on reducing unemployment instead of inflation and may allow inflation to rise at the start of their term.

Five decades ago, economist William D Nordhaus published ‘The Political Business Cycle’ in The Review of Economic Studies (Volume 42, Issue 2, April 1975, Pages 169–190). The paper pioneered an analytical framework showing that macroeconomic variables are influenced by political considerations. According to Nordhaus, governments are driven by private interest and focus on reelection. They exploit the short-term Phillips curve and benefit from voters’ naïve expectations to achieve this. The theory also states that since voters are generally concerned about unemployment, incumbents improve their reelection chances by increasing inflation so unemployment falls just before the election. After the election, the government faces high inflation and then implements austerity, leading to more unemployment. [Éric Dubois. Political Business Cycles 40 Years after Nordhaus. Public Choice, 2016, 166 (1-2), pp.235-259]. Unemployment and inflation are thus subject to cyclical fluctuations linked to the electoral cycle, called “political business cycles” (PBCs).

Nordhaus was, however, not the first to identify the PBC, as others had discussed the concept for at least two decades before his paper. His work became popular because of its analytical model and the timing of its publication. It appeared during a period of increasing instability in macroeconomic variables, especially inflation. According to economist Eric Dubois, “These fluctuations, when not expected, are sources of uncertainty that penalize investment and undermine growth. Economic scholars were searching for the origins of this instability, and Nordhaus (1975) provided an answer: the volatility of inflation comes from electoral manipulations.”

Since the introduction of the PBC theory in 1975, a large body of literature has emerged over the next five decades examining political business cycles in various contexts. These studies on PBCs argue that economic activities are likely influenced by political elections. For example, governments often adopt expansionary fiscal and, in election years, monetary policies. Fiscal expansion includes tax cuts and spending increases to attract voters. The studies also argue that in an election year, the economy usually improves due to large amounts of spending on political campaigning.

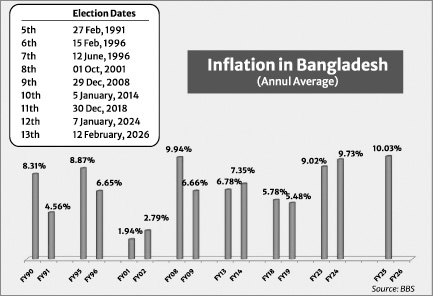

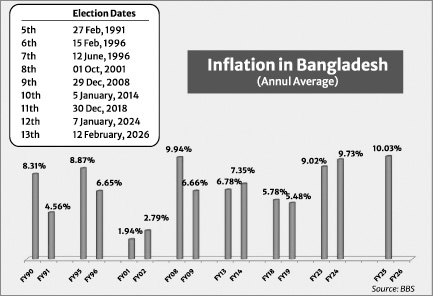

This article briefly reviews annual inflation trends in the election year and the year before the election over the last three and a half decades in Bangladesh. During this period, the country held seven parliamentary elections, from the 5th to the 12th national polls. The 6th and 7th elections, held only four months apart in the same fiscal year, are not considered separately.

It is to be noted that the 6th election was critical to uphold the constitutional obligation. Hasina-led Bangladesh Awami League (BAL) launched a movement pressing for a caretaker government, which turned violent by mid-1995. Khaleda Zia, the then prime minister and leader of BNP, finally agreed to meet the demand as the movement seriously disrupted economic activities. She was, however, adamant to hold the 6th national election under the party in power. So, the election took place on February 15, and BNP won an overwhelming majority as the major opposition parties, namely BAL, Jatiya Party, and Jamat-e-Islami, boycotted the poll. Khaleda took oath for the second time as the PM, and the short-lived parliament passed the 13th amendment to the constitution, which included a provision for a caretaker government to conduct national elections in the country. Following the amendment, Khaleda’s cabinet handed over power to Chief Justice Muhammad Habibur Rahman, who became the chief advisor, or head, of the caretaker government.

Inflation in election years over the last three decades and a half showed a mixed pattern: it increased after elections four times and declined three times. For example, the annual average inflation rate was 8.31 per cent in FY90, the year before the election, and dropped to 4.56 per cent at the end of FY91. The fifth national parliamentary election was held on February 27, 1991. Annual average inflation also rose to 2.79 per cent in FY02 from 1.94 per cent in FY01, with the eighth parliamentary election on October 1, 2001.

Various factors may influence inflation after the polls, such as the new government’s immediate steps to contain price pressures. The expectation of post-election socio-economic stability also plays a key role. The money supply, which was presumed to increase before the polls, moderated, easing inflationary pressure. Once elected or reelected, the government may not focus on inflation and instead spend heavily on development activities. As a result, the money supply increases, pushing inflation higher.

The time gap between election days and the end of fiscal years is also important, though no consistent trends appear. For example, inflation rose to 7.35 per cent at the end of FY14, with the election on January 5, 2024. Inflation declined to 5.48 per cent in FY19 from 5.78 per cent in FY18, following the December 30, 2018, election. In both cases, there was a 6-month gap between the election and the fiscal year-end.

The inflation trend during election periods suggests the PBC has a weak presence in Bangladesh. The PBC theory relies on the unemployment-inflation link, which is largely absent in Bangladesh because of limited labor data. However, fluctuations in economic growth during election years also deserve review, as voters like growth and dislike inflation and unemployment. The election-growth correlation is also important in identifying the presence of PBC, and this column will try to focus on the issue in another article before the national election.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.