Published :

Updated :

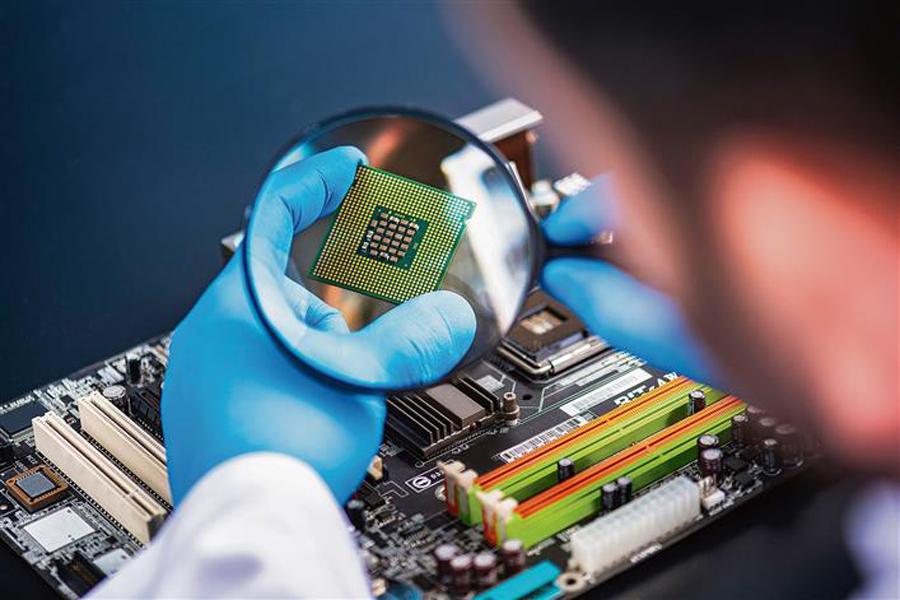

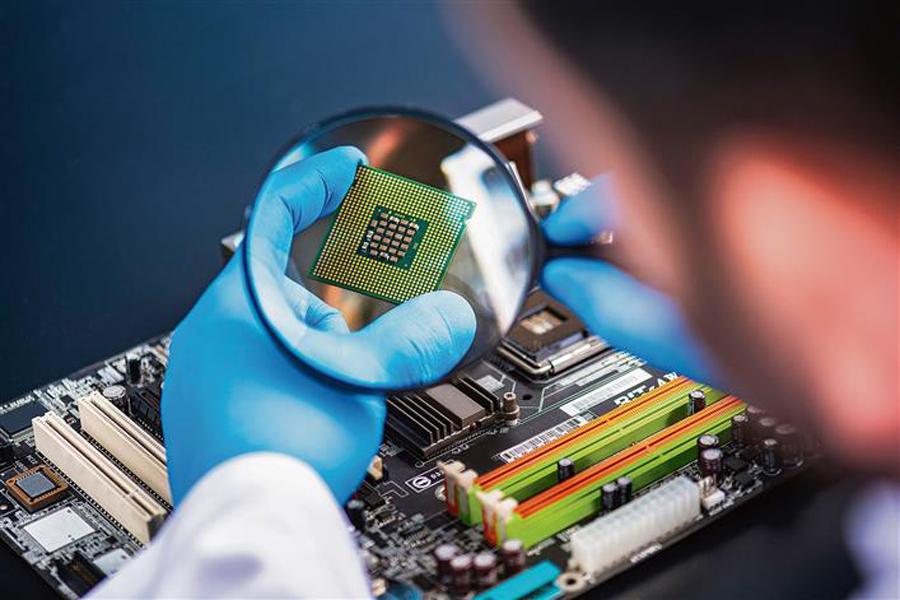

In his book "Chip War: The Fight for the World's Most Critical Technology," noted American economic historian Chris Miller, argues, "Microchips are the new oil. This vital and precious resource has an even more profound impact on people's lives than oil". In the book, which has been named the Financial Times Best Business Book of 2022, he says microchips are "the most complex piece of machinery ever assembled by humans, and there is no other item with a greater influence on globalization and international politics."

To put it simply, the microchip, also known as an integrated circuit (IC), is a small piece of silicon that contains a complex network of electronic circuits. These chips are fundamental building blocks of modern electronic devices for a vast array of functionalities. Their demand is currently exceeding all initial expectations. From guiding complex missiles to heating your morning coffee, microchips are the hidden heroes behind everything from smartphones and televisions to the refrigerators and washing machines that keep our modern lives running smoothly. What's intriguing is their capability to manage numerous tasks, including processing, memory, storage, logic control, digital communication, sensing and detection, and power management. As technological progress marches forward, semiconductors are poised to become even more integral to the majority of devices used by humans in the future.

The global semiconductor market is a trillion-dollar powerhouse in the making, surging at 20 per cent annually. It is no surprise tthat a fierce global race is on. Tech giants like the US, China, South Korea, and Japan are pouring billions into securing their slice of the pie by increasing domestic chip production. Fueled by the US-China tech war and potential disruptions in Taiwan, the race for semiconductor dominance has become a top global priority.

In the USA, the Biden administration's recent allocation for the semiconductor industry includes a $39-billion investment to help companies build more factories and boost domestic production. In 2022, President Joe Biden signed the Chips and Science Act, which provides federal funding, loan guarantees, grants, tax credits, and other support for domestic chip-making investments. Responding to these government incentives, Intel, the American multinational corporation, unveiled its plans to spend $100 billion in four U.S. states to build and expand semiconductor factories.

Meanwhile, China is also redoubling its efforts to dominate advanced technologies of the future by setting up its largest-ever semiconductor state investment fund. Beijing's latest investment, a staggering $47.5 billion, is allocated to semiconductor R&D and manufacturing. Seeking a foothold in this vital industry, India is also accelerating its efforts to become a global hub for semiconductor manufacturing. The Indian government's Semicon India Program, approved by the Union Cabinet, plans to invest approximately $10 billion in developing a semiconductor and display manufacturing ecosystem. This initiative focuses on chip design and display fabrication, aiming to position India as a "premier global location for electronic design and manufacturing."

Amidst this global race of big powers, recent hype about Bangladesh's 'huge potential' in the semiconductor industry is intriguing. Projections suggest that Bangladesh could earn $10 billion from semiconductor manufacturing by 2041 with proper policy support. Bangladesh is a new kid on the block, currently earning around $5 million a year through providing microchip design services. Local companies, however, have not yet ventured into the more advanced stages of chip development, such as fabrication, packaging, assembly, and testing.

Experts believe that a skilled workforce shortage is the primary hurdle Bangladesh must overcome to become a serious player in the semiconductor industry and capitalise on its enormous potential. Despite an annual output of approximately 25,000 graduates in Computer Science and Electrical Engineering, and relevant courses offered by some universities and technology institutes, fresh graduates reportedly lack the technical knowhow required by the industry. Their academic knowledge of semiconductors seems inadequate for professional application, hindering companies' expansion plans.

To cultivate a high-end talent pool for specific roles in the semiconductor industry, experts advocate for a well-coordinated effort between private sector companies, academia, and the government. This strategic partnership requires investment in education and training programmes focused on chip design, microfabrication, and other critical areas. Collaboration with established global technology partners can further strengthen these programmes by incorporating best practices used in leading semiconductor nations. Universities and institutes should introduce relevant subjects like VLSI design, microelectronics, and nanotechnology into their curriculum, equipping students with a comprehensive understanding of IC design, production, packaging, and fabrication from an early stage. In addition, comprehensive and practical training programmes for engineering graduates, potentially through internships or joint research initiatives, can empower them to become competent professionals and address the industry's specific needs.

Looking at international examples, Bangladesh can take a leaf out of China's book. China has strategically shifted its educational focus to produce skilled human resources for the semiconductor industry. This involves establishing dedicated integrated circuit schools within universities, and offering specialised degree programmes in fields like semiconductors, chips, and integrated circuits. These programmes foster a pipeline of highly skilled professionals and emphasise the development of top-level research talent, potentially culminating in master's and PhD degrees. Bangladesh could benefit from adopting a similar approach, focusing on developing a comprehensive educational infrastructure to cultivate talent in this critical and highly profitable sector.

Furthermore, to accelerate the growth of its semiconductor industry, Bangladesh could consider engaging in bilateral dialogues and workshops with experts from leading producers like Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan. This knowledge transfer would be crucial alongside efforts to nurture a business environment conducive to semiconductor manufacturing. This includes streamlining regulations, ensuring access to necessary infrastructure, and providing tax breaks and other incentives. Besides, attracting foreign investment, fostering public-private partnerships and formulating policies that support domestic technology development will be essential for long-term success.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.