Published :

Updated :

It has long been argued by critics that social enterprises are exploiters, owners of which pay less than poor craftsmen or milk producers and women deserve but pocket hefty profits by selling products in the market.

But a case study on Aarong for example, tends to show how they impart immense social and economic impacts on the poor households in rural Bangladesh. The social enterprise theory espoused by many suggest that, as opposed to philanthropic philosophy, the poor could be made entrepreneurs themselves given that the mismatch between endowments and opportunities - called binding constraints -- were removed or eased. And in recent years, there is an increasing urgency among developing economies to promote market-based initiatives that offer sustainable business and consumer solutions to disadvantaged groups.

We reckon that a new perspective on the phenomena of chronic poverty, offered by eminent economist S.R. Osmani of Ulster University, could be relevant in the context of social enterprise and poverty reduction in Bangladesh. Osmani's theory is based on the notion of a mismatch between the structure of endowments possessed by the poor and the structure of opportunities open to them. It is a certain departure from the traditional view of 'poverty trap' that adduces poverty mainly to the lack of endowment of assets rather than to the composition and structure of those assets. In other words, as Osmani opines, what matters for poverty reduction is the pattern of growth rather than the growth itself.

Aarong Dairy (AD) is a case in point. It was born to connect farmers with markets, possibly to match endowments of the poor with opportunities available in the market. Started in 1978 with the motto of linking artisans with the market, AD expanded with the passage of time taking up dairy development in the country and thus helping the poor. The economics is quite clear. On an average, a household owns a cow in rural areas. For many households, it is the only non-land asset in possession. But due to the lack of a market link or shortage of knowledge about how to turn it into a stream of income, the output of the cow (say milk), can do no good to the poor household.

AD is reported to account for about one-fifth of the Bangladesh's total dairy market share. Milk is being collected from poor households, 101 chilling stations keep the milk fresh and strict method of maintaining quality is ensured. Unlike private enterprise's hunger for profit only, the cattle development fund of AD provided, in 2015, subsidised artificial insemination services to 6,500 farmers, vaccinated 25,600 heads of cattle, delivered 8,000 kg of free fodder seed and trained 2,000 farmers on animal husbandry methods. In 2015, Aarong collected over 16 Olympic-sized swimming pools or 42 million litre milk through the extensive network of rural dairy farmers. The social enterprise processes the milk to produce a wide range of dairy products which are sold through retail and modern trade channels across Bangladesh. Reportedly, 50,000 dairy farmers produce best quality outputs. AD, one of the largest social enterprises, employs about 1,500 people and famers produce over 250,000 litre milk a day. Any surplus goes to sustainability of projects and the creation of new opportunities. We reckon that during the last four years, faster development had taken place.

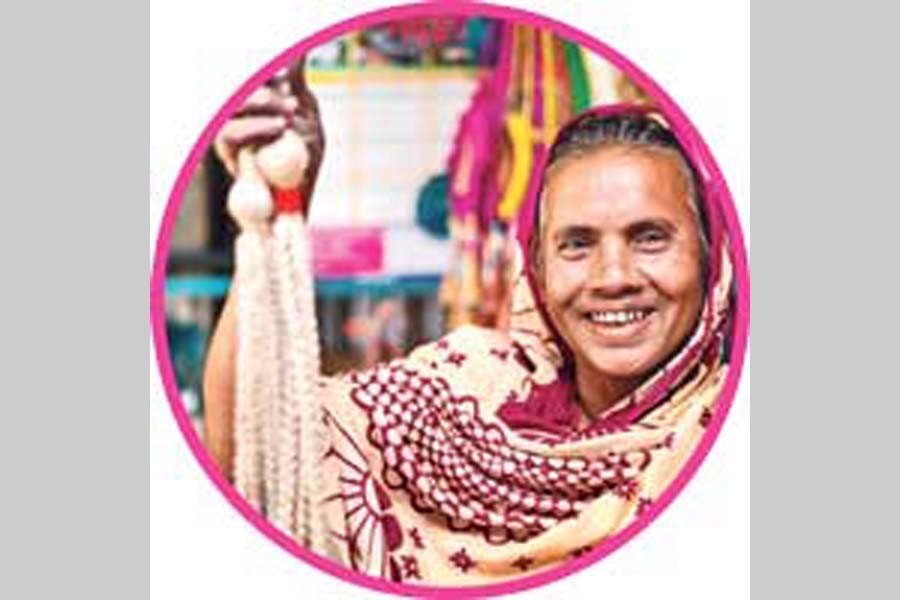

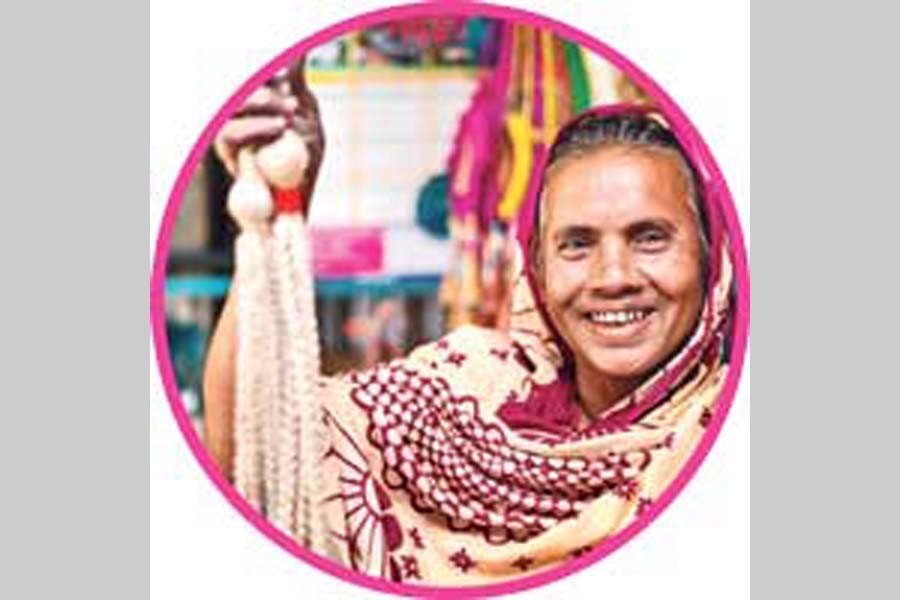

Take the case of yogurt made from milk. Bangladesh has been witnessing rising per capita income over time and, with that, an increase in the demand for income-elastic goods and services. While people grow urban they still remain rural in the sense that even highly income-elastic product such as yogurt comes from rural areas. Seeping through the cup of yogurt the urban consumer hardly realizes that the yogurt cup has changed the landscape of livelihoods of the rural hard-core poor. Yogurt that a mother in an urban area buys each day for her child is the reason why another mother in rural Pabna, is able to send her children to school. As a life history review shows, the Pabna mother's life was unpredictable for many years. Very low income of her husband - an irregular mason worker -- and the need for next meal for family members or for children's education-- used to keep her in a quagmire. Desperate, she borrowed money to buy a calf and start a dairy farm. Initially she had to rely on local milk buyers who forced on her feeble profit, but later partnered with AD to be on an even keel.

The lesson is simple. First, with dwindling flow of aid and grants, philanthropic philosophy should pave ways to self-reliance mode where social enterprises can play a pivotal role in helping the poor live a dignified life. Second, to prepare the poor for the market, endowments must be aligned with market demand. As in the case of AD, a team of veterinarians guide cattle farmers in initial stages, providing with animal husbandry training, basic animal health care and artificial insemination services.

As the farms grow farmers continue to get support for cattle rearing and management. Following the Pabna mother, 15 other households in her village as well as from nearby villages started their own farms. She became a 'consultant' to her poor comrades in and around the villages. All of them now have the most productive homestead dairy farms in Pabna. Her own small farm now boasts five cows and 11 bullocks. She saves every month and purchases one cow every year by the savings. Thus, poor she entered, solvent she survives.

Abdul Bayes is a former Professor of Economics at JahangirnaagrUniversity and currently an Adjunct Faculty of East West University.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.