Published :

Updated :

The warning signs are unmistakable, and the consequences are no longer abstract. The growing presence of harmful chemicals in the Bangladeshi food chain now poses a direct threat to every family in the country -- a slow-moving public health emergency unfolding in plain sight. Rising levels of toxic substances in everyday food have triggered deep concern among ordinary citizens, scientists, and policymakers alike. Yet concern alone is no antidote. What Bangladesh needs, urgently and unequivocally, is coordinated national action.

At a high-level meeting chaired recently by Chief Adviser Professor Muhammad Yunus, public health experts, regulatory chiefs and senior administrators laid out what many have long feared but never publicly acknowledged with such clarity: Bangladesh's food is increasingly contaminated, and the country is running out of time to respond.

"We are aware of the contamination, but we must now decide how to confront it," Yunus said. "Our children, parents, and loved ones are all affected. In our own interest, we must work together. Some actions must begin immediately." The statement was calm in tone but seismic in implication -- a reminder that food safety is not merely a technical challenge, but a moral one. When children sit down to eat, their parents expect nutrition, not neurological damage.

What we know so far is alarming. According to the World Health Organization, one in ten children globally suffers from foodborne illness annually, and a third of these cases result in death. Bangladesh -- heavily populated, climate-stressed, and agriculturally intensive -- sits precariously within this global picture. The meeting was informed that the country records nearly 30 million child infections every year. Each one is a preventable tragedy. Each one represents a system that is failing both consumers and those future citizens whose bodies are still forming.

The data emerging from laboratories confirms what many had suspected but few could quantify. In a recent round of testing, excessive lead or lead chromate was detected in 22 out of 180 food samples. Over the last fiscal year, 1,713 samples were analysed; this year, the figure has already reached 814 -- a sign of growing institutional attention, but also proof of how far we remain from comprehensive oversight.

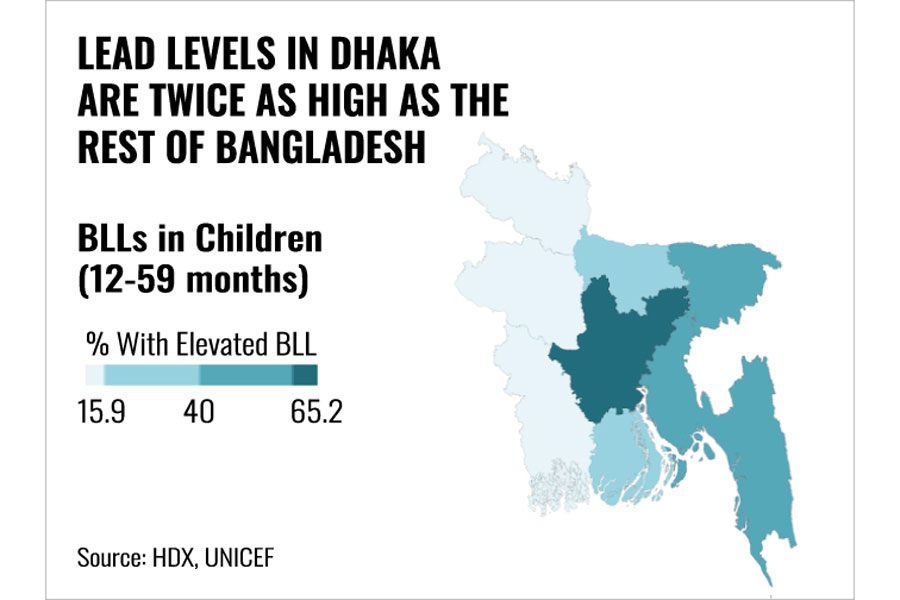

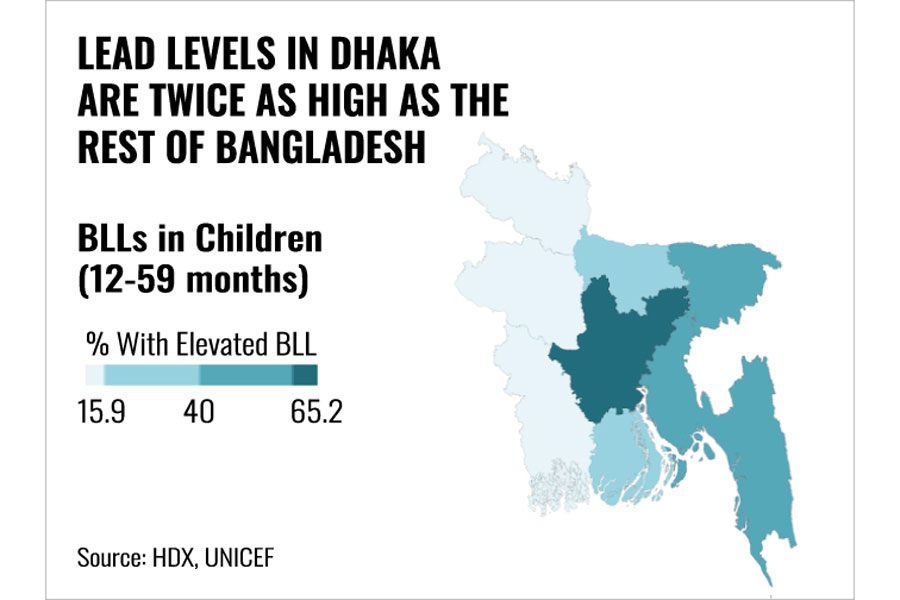

Lead is not a benign contaminant. It accumulates silently in the body -- in the brain, liver, kidneys, bones, and teeth. In children, whose bones are softer and blood-brain barriers more permeable, its damage is often irreversible. "Lead accumulates in the brain," officials warned, "damaging cognitive development." UNICEF data referenced during the session indicated that 35 million Bangladeshi children may already be exposed. Another study found traces in around 5 per cent of pregnant women. One might reasonably ask: if this is what we know, what remain the unknowns?

Equally concerning is the creeping spread of pharmaceutical and industrial residues in food and water systems. A joint study conducted by Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University, Bangladesh Agricultural University, and UMEA University in Sweden detected more than 300 pharmaceutical chemicals, 200 pesticide compounds and 16 types of PFAS -- the so-called "forever chemicals" -- in fish and water samples across several regions. These compounds do not simply wash away. They bioaccumulate, moving from river to fish, from fish to plate, from plate to bloodstream, ultimately becoming part of the nation's biology.

The story is no better in the poultry sector. Antibiotics -- often administered liberally to promote rapid growth or prevent infection -- can remain in chickens for seven to 28 days. But the market rarely waits that long. Poultry is often sold mere days after treatment, residues intact, resistance-building microbes alive. Large commercial producers generally follow safety protocols, but countless smaller, unlicensed operators do not. They operate outside regulation, outside accountability, and outside public health interest. Their profit comes at the cost of the nation's immune system.

This rising tide of contamination is not merely a failure of industry. It is also a failure of governance. Ministries responsible for agriculture, health, fisheries, and commerce frequently operate in silos, while regulatory bodies -- including BSTI, the Consumer Rights Directorate, the Bangladesh Food Safety Authority (BFSA) and the Atomic Energy Commission -- lack a unified national enforcement backbone. Fragmented oversight breeds loopholes, and loopholes breed contamination.

That is why the call emerging from the recent consultation must not be ignored: Bangladesh needs an integrated national plan, one that brings ministries, regulators, scientists, universities, and local governments under a single operational agenda. Food safety is not an agricultural issue alone; it is a national security concern, an economic concern, an educational concern. A sick nation cannot work, cannot learn, cannot grow.

Priority actions are within reach. Every public university in Bangladesh has laboratory capacity to conduct contamination testing -- a profoundly underutilized national asset. A coordinated testing network could dramatically accelerate detection, enabling real-time public reporting and rapid regulatory response. Cutting illegal pesticide imports, expanding farm and market inspections, establishing traceability systems, and increasing penalties for violators are not novel ideas. They are overdue obligations.

At the production level, the race to maximise yield must stop overriding the obligation to ensure safety. Bangladesh has rightly taken pride over the decades in its strides toward food sufficiency, but sufficiency without safety is a hollow achievement. A plate full of poison is not a mark of progress.

Climate vulnerability, population pressure, and industrial expansion make this task harder each year. And yet the country also possesses tools that could turn the tide: scientific talent, a network of universities, a growing consumer voice, and administrative machinery that -- if mobilised -- can still execute large-scale policy. The missing ingredient is collective resolve.

Change, however, cannot be driven from government alone. Public awareness is essential. Food safety must be understood not as a distant regulatory term, but as a daily survival concern. Media must report not only on contamination scandals but on solutions, accountability, and research. Schools must teach food safety alongside nutrition. Children should grow up knowing not just how to eat, but how to question what they eat.

As one expert noted during the meeting, "Ensuring enough food sometimes means we forget whether what we eat is safe." This forgetting is a luxury no country can afford.

Bangladesh stands today at a critical threshold. It can ignore the warning signs -- burying evidence beneath bureaucratic delay -- or it can take decisive action to safeguard the next generation. The choice is stark: act now, or accept a future in which illness becomes normal, economic productivity declines, and the health of children becomes collateral damage in the pursuit of output.

Urgent action is not merely desirable. It is non-negotiable.

Contamination is creeping into our rice, our fish, our poultry, our vegetables, our soil, and even the water that sustains us. A nation cannot be strong if its children are chemically weakened. A population cannot thrive if its contaminated food slowly poisons it. The gap between alarm and action must now close -- fast, firmly, and with scientific precision.

This is Bangladesh's warning bell.

The question that remains is whether the country will answer it.

mirmostafiz@yahoo.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.