Published :

Updated :

Air pollution in Dhaka has reached such an alarming level that it is now being dubbed a silent killer. The city's air is heavily polluted with fine particulate matter (PM2.5), contributing to a wide range of health issues, including respiratory problems, lung cancer, and heart disease. It has become routine for the Air Quality Index (AQI) to classify Dhaka's air as hazardous, severely polluted, or unhealthy-consistently placing it among the most polluted cities in the world. Clean air has become such a rarity that, according to a study by the Center for Atmospheric Pollution Studies (CAPS), Dhaka experienced clean air on only 31 days over the past nine years. These alarming statistics underline the need for urgent, effective interventions. Yet, rather than addressing the root causes, the city authorities continue to pursue superficial solutions-the latest being a plan to install air purifiers in open public spaces.

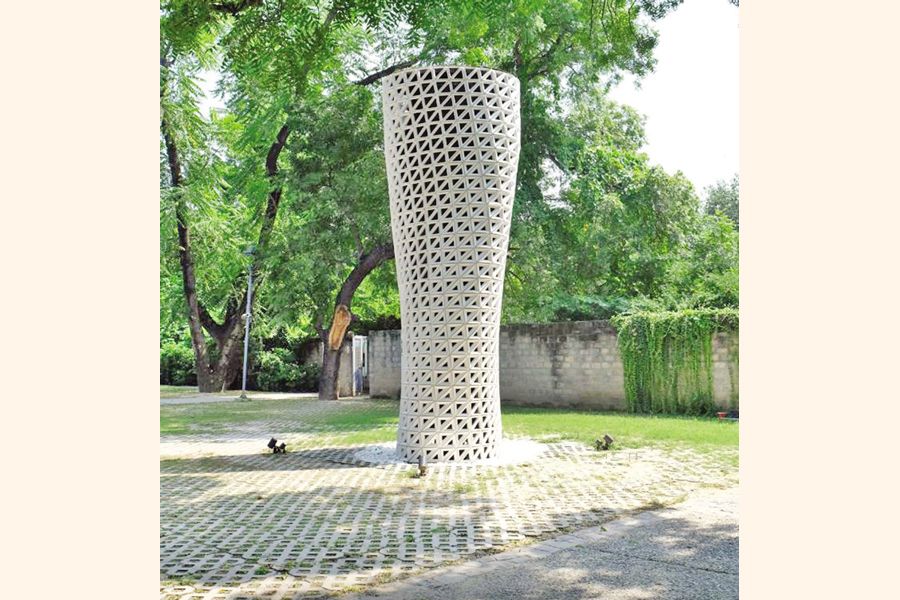

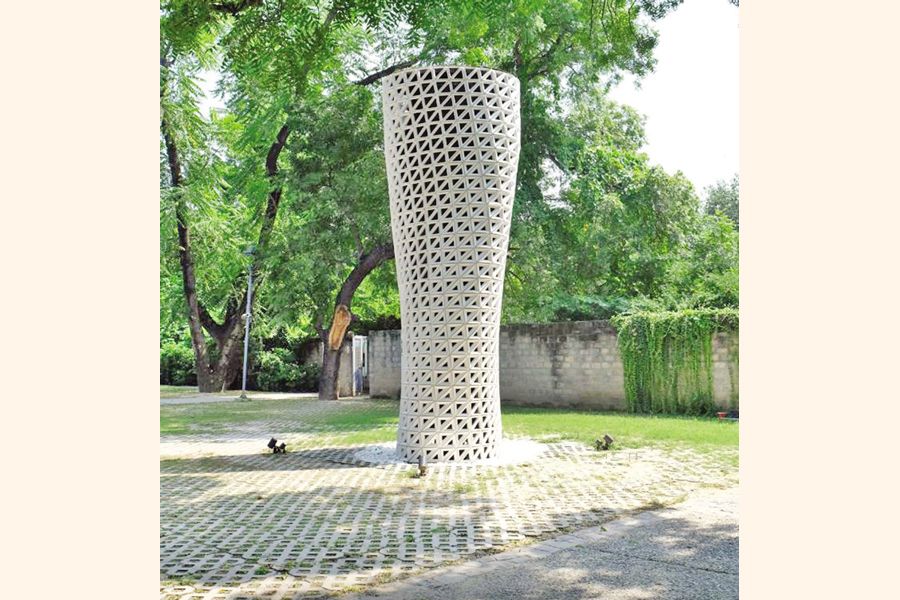

The Dhaka North City Corporation (DNCC) has proposed installing 50 industrial-grade air purifiers in various locations as a quick-fix solution to the crisis. Officials have claimed that each device would clean and cool the air much like 100 trees. But if that is the case, one must ask-why not plant 5,000 trees instead? Trees purify air over a wide area and offer ecological, psychological, and climatic benefits-advantages that mechanical purifiers simply cannot replicate.

Each purifier is expected to cost between Tk 5 to 6 million, not including substantial electricity and maintenance costs. While the DNCC administrator has expressed confidence that the initial costs will be met through Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) funding, the city corporation will remain responsible for ongoing expenses, including frequent filter replacements. According to one estimate, the annual electricity cost for operating these high-voltage machines could be more than enough to cover the expense of planting 5,000 trees.

Moreover, the effectiveness of these devices in open spaces remains highly questionable. Air purifiers are typically used in enclosed environments such as hospitals, shopping malls, and office buildings. In open spaces, their efficiency plummets due to the constant movement of air. The DNCC claims each purifier can clean up to 30,000 cubic feet of air per minute and remove 90 per cent of fine particles. However, experts point out that even a light breeze-just 2 metres per second-is enough to quickly replace purified air with polluted air, rendering the effort largely ineffective.

Experience from other countries lends further weight to this skepticism. Delhi's 24-metre smog tower, once touted as a groundbreaking solution, was ultimately declared ineffective by the Delhi Pollution Control Committee. A 2019 test by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) found the impact of such purifiers to be "very small to non-existent." The Rs 20 crore ($2.4 million) tower, which had promised to reduce pollution by 50 per cent within a 1-kilometre radius, failed to show any meaningful improvement within a year. In practice, the benefits of such installations dissipate within a few hundred metres.

Many, therefore, believe that although the DNCC's initiative may be well-intentioned, it risks wasting time and public resources while creating an illusion of progress. Worse still, it could divert attention from the more pressing task of addressing the root causes of air pollution. There are also concerns about equity and inclusiveness. When many parts of the city still lack essential services such as proper housing, sanitation, and access to clean water, projects focused on installing expensive air purifiers in affluent areas will be both extravagant and discriminatory.

The sources of Dhaka's air pollution are no secret. A 2023 study by the Department of Environment (DoE) and the World Bank found that 58 per cent of PM2.5 emissions come from brick kilns, 18 per cent from vehicles, 10 per cent from construction dust, and 14 per cent from open waste burning and industry. Effective mitigation efforts must, therefore, target these sectors through stricter regulation, cleaner technologies, and better urban planning.

Meanwhile, Kolkata offers a model worth studying. Compared to other Indian megacities like Delhi and Mumbai, where AQI levels remain poor, Kolkata has made measurable progress in improving air quality. And no, it did not rely on air purifiers to do so.

One of Kolkata's key strategies has been the promotion of greener public transportation. The city has invested heavily in electric buses and ferries, aiming to deploy 5,000 electric buses and a fully electrified ferry fleet on the Ganges River by 2030. This shift is expected to significantly reduce carbon emissions and operational costs. Since 2008, the West Bengal government has also been phasing out buses older than 15 years.

To combat dust pollution, the Kolkata Municipal Corporation (KMC) has introduced mandatory guidelines for construction sites, requiring them to cover exposed areas, keep soil damp, and recycle construction and demolition waste into building materials like tiles.

The city has also embraced extensive tree plantation as a core strategy. KMC, in collaboration with NGOs and community groups, has launched urban forestry initiatives to increase green cover. Native species such as Neem, Banyan, Peepal, and Gulmohar-known for their high pollution-absorbing capacity-are prioritised. These efforts have helped reduce urban heat, improve biodiversity, and enhance the overall quality of life.

Kolkata's multi-pronged approach to tackling air pollution offers a pragmatic and evidence-based framework that Dhaka would do well to emulate. Planting trees, modernising transport, regulating construction sites and industrial emissions, closing down illegal brick kilns -these are not quick fixes, but they are sustainable. Real progress will require strong political will, strategic planning, and active public participation. Only then can the city's residents hope to breathe clean air.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.