Published :

Updated :

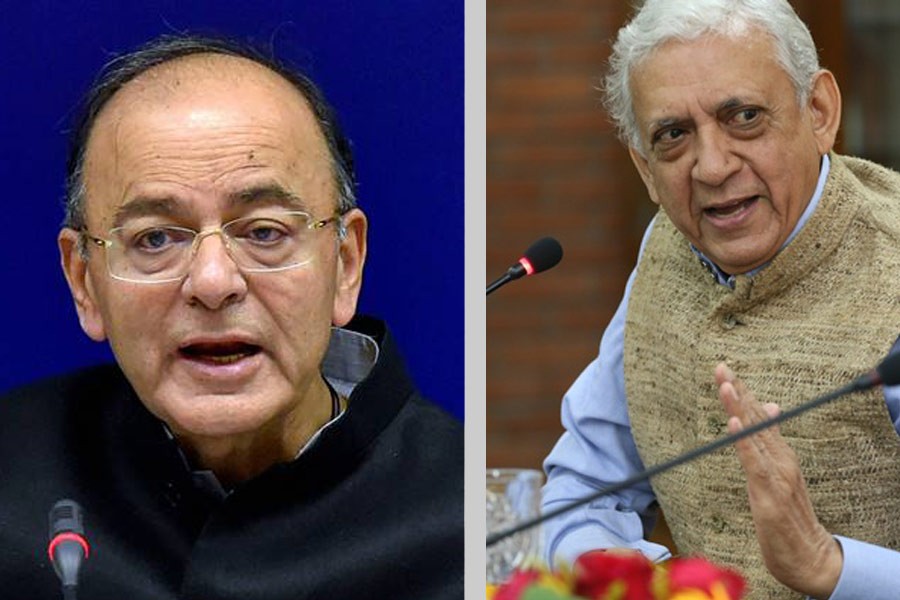

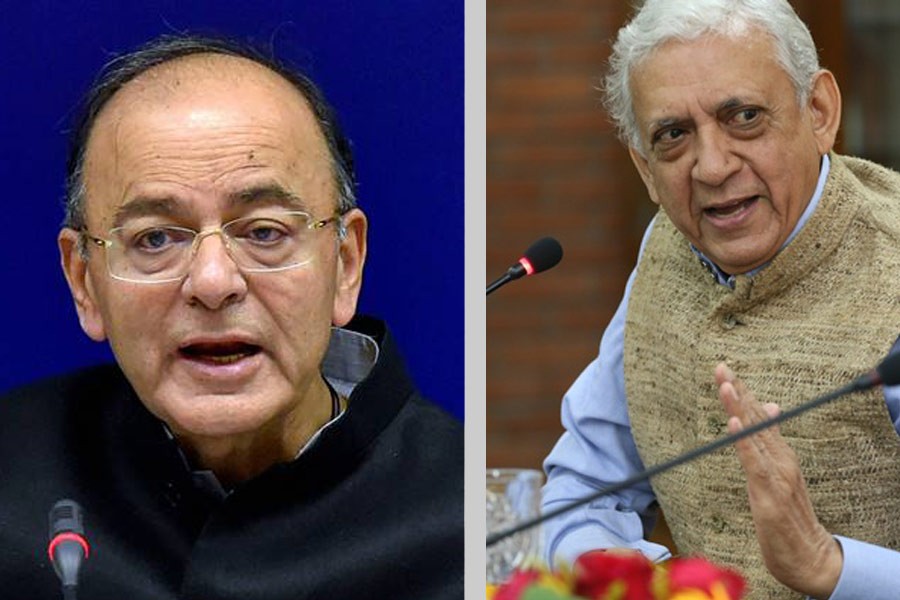

No free political marketplace can always be expected to uphold unity and like-mindedness among participating actors. In a tumultuous October of 2017, this observation seems to be particularly true on India's eastern front. On the one hand, India's Finance Minister Arun Jaitley came to sign a US$4.5 billion loan for Bangladesh, carrying a nominal 1.0 per cent interest rate and a 20-year repayment play. On the other, were Gowher Rizvi's observations, as Bangladesh Prime Minister's Adviser, at the "Eighth Bangladesh-India Security Dialogue" on October 10, sponsored by the Bangladesh Enterprise Institute (BEI) and New Delhi's Observer Research Foundation (ORF). Behind the strategic importance of strong Bangladesh-India relations, he could not help but note such wrinkles as Indian loans being too lethargically released to make the necessary dent; Teesta talks thwarting trust; even more emphatically, indicating the many more Rohingya developments behind the scenes than up-front, as if alluding to an ever-bloating suspense balloon approaching a bursting point without expeditious resolution.

On the positive side, Rizvi applauded that India remains the largest aid-supplier for resettling incoming Rohingyas; while Jaitley went overboard to inform his well-heeled audience that this was not only the largest loan India has given any country, but also the largest Bangladesh has ever received from anywhere. Both Bangladesh and India, it seems, cannot but be a vital part of each other's national interest. Yet the growing puzzle is if that interest reflects a convergent or suddenly diverging viewpoint.

India's stance towards Bangladesh may be more light-shedding than Bangladesh's towards India, more so in Dhaka than New Delhi: after all, as headquarter of resolving the Rohingya crisis, Dhaka is more hands-on than New Delhi, in addition to being the locus of India's Act East policy-approach, and more single-minded over Teesta than anywhere else in India, except perhaps Mamata Banerjee's Kolkata. It has also steadily become the most accessible large market of India among India's neighbouring countries.

Jaitley spent more time and attention in Sonargaon Hotel presentation on India's cash-less revolution under Narendra Modi's financial inclusion programme (the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana, for example) than the loan itself. Meant to augment costs of 17 crucial Bangladeshi infrastructural projects, like the Padma Bridge, it carried a strong 'connectivity' message with India. Yet, and this may soon become the crux, the loan accentuates a one-way flow favourable largely to India: it targets Bangladesh more as a consumer of India's goods and services than as a producer of consumer goods and services within India. For a start, there is the yawning trade imbalance that Bangladesh just cannot even begin reducing given the constraints: protectionist measures stifle many Bangladeshi exports from even entering India, particularly from the ready-made garment (RMG) sector. Then structural inequality riddles every other exchange: Tata trucks dominate our highways, white-collar Indian employees remit a sizable chunk of our precious foreign-exchange earnings, and an increasingly formidable frontier-blockade only deepens a suspicious mindset on both sides. If, against this, India's 'cash-less' experiment is now to be re-enacted across the Gangetic plains, then the playing field asymmetry may speak louder than postulated benefits. More disturbingly, the chances of some groups within the country fanning Islamic flames may grow unnecessarily, chipping an active sine qua non bilateral relationship between Bangladesh and India and a potential one between Bangladesh and Myanmar. India will ironically have cultivated the same Islamist forces within Bangladesh that it is fearing will spread to Bangladesh from Rakhine.

Shifting to those refugees, Modi's September identity with Aung Sang Suu Kyi, the author of the UN-dubbed Rakhine ethnic-cleansing, raised more than eyebrows. True, lower-level Indian officials have seriously and sincerely sought to smoothen ruffled Bangladeshi feathers ever since, but perceptions of the ceremonious Jaitley visit diverting attention from the graver Rohingya and Teesta issues cannot easily be discounted.

At stake may be the causal Rakhine factors; and increasing global attention rivets upon China's and India's roles within this context. For example, India's plan to build a port in Sittwe, smack middle in Rakhine territory, as the crown jewel of a highway into India's northeastern states, obviously requires the eviction of at least a handful of Rohingya communities. The same is true of China's more advanced Myanmar plans, of which building a US$7.3 billion oil/gas pipeline from a new deep-sea port, Kyaukpya, to Yunnan Province, also necessitates land eviction. Lee Jones of Queen Mary University of Politics and International Relations and Saskia Sassen of Columbia University in the United States argued even before the current Rohingya influx how 'business interests' and 'land-grab' may be far more accurate explanations than religious/ethnic differences. If these sparked the ethnic cleansing, China and India must be held responsible by the world community instead of being allowed to camouflage their human rights violations with attributions to Islamic extremists. Though intelligence officials acknowledge how the Arakanese Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) is being led by a handful of Pakistani Islamicists, to go from there to ethnic cleansing may be a bridge too far for even Taliban in Afghanistan or Islamic State in Syria/Iraq. Erecting an unnecessary Trojan Horse only complicates a negotiated outcome and corrodes the trust Bangladesh places in bilateral relations. Bangladesh has turned to both China and India to mediate the refugee invasion only in the hope of giving them the chance to rectify the wrong wrought, not to further thicken the plot.

These cannot alone explain India's broader eastern woes. Without the Sittwe port, the 1,350km Trilateral Highway from Moreh, Manipur in India to Mae Sot in Thailand (itself an extension of the 2001 Indian-Myanmar Friendship Highway), cannot be brought out of the freezer where it has been ever since it was proposed in 2002, especially as China makes more strides with its own gas/oil pipeline project in Myanmar. Both those heavyweight countries just went through the embarrassing Doklam stand-off adjacent Bhutan; and the stalemated outcome left India too much on the back foot to fit Modi's invincibility aura. In other words, reasserting Indian interests in other theaters of the crucial contestation space between South Asia and Southeast Asia is gaining greater salience than the Act East policy approach originally envisioned.

Earlier Bhutan pulled out of the much vaunted Bangladesh-Bhutan-India-Nepal (BBIN) highway, largely out of an environmental concern. Bangladesh itself labours at the short-end of dealings with India. While using Bangladesh as an assumed bridge to bring its northeastern states into the mainstream, India may be taking too much for granted and all too unilaterally. If both of the major South Asian players do not pause to blink, the toll taken on their envious economic performances may become too heavy for even iron-fisted political heavyweights to bear. Already India's own 2017 projected growth-rate is falling behind schedule, in part due to the uncertainties caused by the cash-less shift; while the World Bank is projecting, for the first time, how Bangladesh's 2017 growth-rate will cross the 7.0 per cent mark. Imbalances have a habit of hurting. Both countries have shown enough maturity to avoid that pathetic outcome.

Dr. Imtiaz A. Hussain is Professor & Head of the newly-built Department of Global Studies & Governance at Independent University, Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.