Published :

Updated :

Journalism is not only a profession; it demands passion, devotion and commitment. It also comes with the responsibility to serve readers, viewers and listeners with unbiased information and perspectives they need to make important decisions in everyday life.

Aspiring journalists may wonder how they can blend all these qualities into their work while playing different roles—as correspondents in local media outlets, local reporters for global media houses, or staff working at various layers of a newsroom.

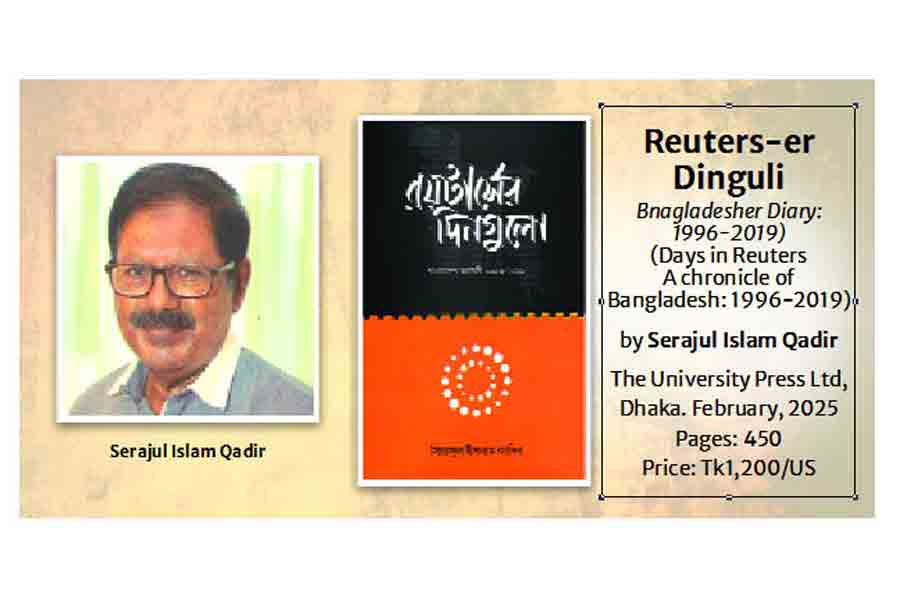

There is no shortage of books guiding journalists, most of them written by Western media veterans in English. However, books that speak of the dynamism of the Bangladeshi media landscape are hard to come by. That void is somewhat filled by the book titled Reuters-er Dinguli (Days in Reuters). It offers a glimpse into the journalistic journey of Serajul Islam Qadir, former bureau chief and chief correspondent of Reuters, across local and global platforms, and shows how he matured as a journalist over time by learning lessons on the job.

The book also provides brief accounts of noteworthy public events between 1996 and 2019, during which Qadir served the globally acclaimed news agency Reuters. Over that period, the portraits of Bangladeshi politics and power changed time and again, yet his sincerity in remaining true to the details of those events—while mindfully excluding personal judgement—is evident.

The book weaves stories of national pride and tragedy into a broader historical narrative. Readers’ faded memories, for instance, of the first-ever visit of a US president to Bangladesh—William Jefferson Clinton in 2000; of the country’s escape from the Asian economic crisis in the 1990s when Thailand, South Korea and Malaysia were severely hit after their currencies depreciated sharply against the dollar; and of garment businesses’ nightmarish struggle to survive after the United States put Bangladesh on a blacklist following the September 11 attacks on the Twin Towers in New York, will be refreshed.

It is often believed that history is told and read not to judge what was right or wrong, but to understand how we arrived at where we stand today and to make sense of our surroundings. In that sense, Reuters-er Dinguli can serve as a reference for the major political and social developments that unfolded during the period.

If readers can connect themselves to those incidents, they may gain a better sense of our collective future as a nation—or prepare themselves for it—however unpredictable it may be.

As Qadir’s reporting career was largely dedicated to covering economic issues, a major portion of the book highlights economic policies that worked, those that failed, and those that remained on paper due to a lack of political will. Global challenges that had domestic repercussions are also linked to the hardships experienced by Bangladeshis.

The tale of Saleha Begum would soften even minds detached from the harsh realities faced by women who toil every day to secure food and shelter for their families. When she lost her job—alongside countless other women—after a sharp decline in garment orders from the United States following the 2001 attacks, she was forced to work as a housemaid. Many of her former colleagues in the readymade garment sector even resorted to prostitution in a desperate search for survival.

While Qadir sheds light on journalistic practices strictly followed on global platforms to ensure neutrality, he also touches upon social, cultural and economic legacies passed down generations that have become obstacles to the emancipation of the people. Vandalism, killings and terrorism stemming from religious bigotry, as well as human rights violations committed to suppress dissent, are among the major issues that continue to erode Bangladesh’s image on the global map.

The writer also shares his experiences of travelling as a journalist. His personal encounters with eminent personalities—including economists, politicians and activists—offer readers the pleasure of a sense of intimacy with them.

As I delve deeper into the book, my expectations rise, but I feel somewhat disappointed to find that Qadir refrains from revealing the deeper cracks within the Bangladeshi media landscape. Journalists often encounter issues they cannot speak or write about—to protect the interests of the organisations they work for, those in power, or corporate interests. At times, unethical practices are imposed on journalists, or they are adopted for personal gain.

The book could have served as an ideal platform for documenting these unpopular and hidden truths—an exercise essential not only for future journalists but also for readers outside the profession. Insights into the darkest corners of the media would help inspire a movement for positive change.

In today’s world, dominated by the internet and social media, external pressure on journalistic integrity has intensified. It has become increasingly difficult to distinguish journalism from activism, views from news, and information from propaganda. Even with the support of modern technologies, mainstream journalists struggle to maintain authenticity and professional integrity amid the strong tide of viral content.

The challenges newsmen faced daily decades ago have largely disappeared, thanks to the widespread use of mobile phones, easier access to information and greater data availability. However, these have been replaced by competition with self-proclaimed newsmen, additional working hours to detect fake news, and the fight against efforts to silence the voices of the marginalised.

Of course, a book cannot paint the entire media tree, showing all the branches that have sprouted out and every predator that is gnawing at its leaves and bark, but bringing out something that has been pushed under the carpet onto the pages is always what readers expect an author to strive to achieve.

devnathbishakha@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.