Published :

Updated :

Despite humans seldom learning from history although it invariably repeats itself, the rise and fall of empires and civilisations as well as their causes and consequences have always attracted the attention of historians and laymen alike. Treading on this same path, the Swedish scholar cum historian of ideas Johan Norberg has dwelt on the ascension and eventual decline of seven great civilisations (the last one is still in vogue), viz. the Classical Greek, the Roman Empire, Abbasid Caliphate, China’s Song Dynasty, Italy’s Renaissance, the Dutch Republic, and the ongoing Anglosphere. Titled Peak Human: What We Can Learn from the Rise and Fall of Golden Ages, the book has been included by The Economist in the list of best ones published during 2025.

Norberg has also been the author of previous best-selling volumes like Progress: Ten Reasons to Look Forward to the Future (2016), and The Capitalist Manifesto: Why the Global Free Market Will Save the World.

The author explains in this book how the golden agesrise orfallby adding fresh details with provocative arguments. He claims that the common thread that enabled societies to consistently flourish had been their embrace of openness to trade, ideas, and people; but it was their inward withdrawal from the external world that proved to be a decisive factor in their ultimate decline. Openness to ideas and trade made nations strong that propelled spectacular cultural, scientific, and economic advancement. But this growth-path was hindered and decline set in when civilisations lost their outward-looking self-confidence and restricted freedom cum openness, especially in trade and commerce. As Norberg elaborates, “Protectionism might seem like a shield, but it easily becomes a cage. It’s a way of cutting a nation off from the world’s brains and skills, forfeiting not just wealth, but the energy and constant renewal that make civilizations shine”.

Explaining the reasons why he picked the seven particular examples of civilisational prosperity, Norberg says, “Each of them exemplifies … a period with a large number of innovations that revolutionized many fields and sectors in a short period of time”. He elucidates, “A golden age is associated with a culture of optimism, which encourages people to explore new knowledge, experiment with new methods and technologies, and exchange the results with others … Its result is a high average standard of living, which is usually the envy of others, often also of their heirs”.

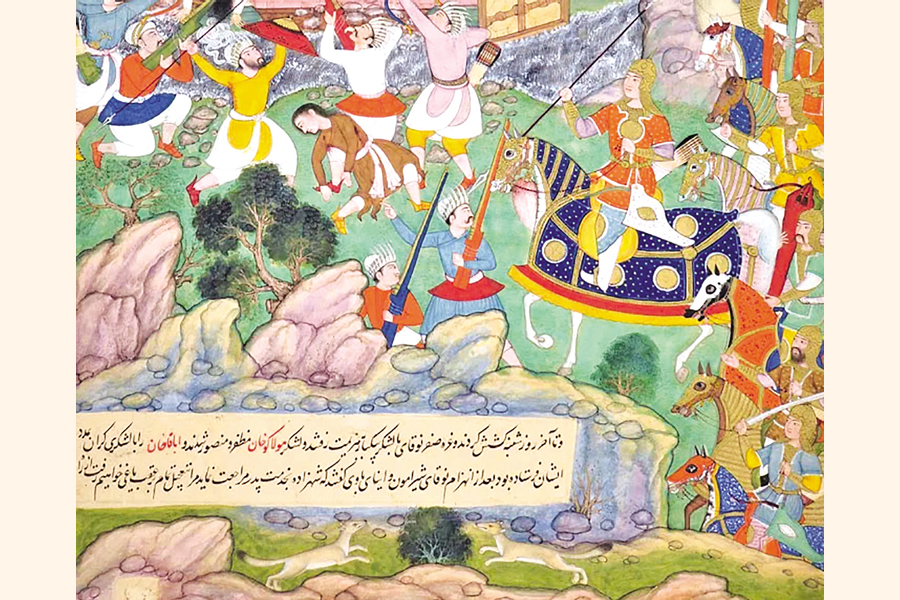

Norberg’s description of the Abbasid golden age sheds some light on the ascendancy of Arab Muslims during the medieval era. Recalling the huge accomplishments of Muslim scholars like Al-Khwarizmi (Algorizmi), Ibne Rushd (Averroes) and Ibne Sina (Avicenna) during the Abbasid Caliphate, he notes that their economy was market-based and the merchants held an exalted position in society. This was exemplified by a trader named ‘Sindbad the Sailor’ whose adventures began when he sailed out of Baghdad in search of commodities and commerce. The bourgeoisie were held in high esteem by the Abbasid society that gave them dignity and freedom. As a consequence, prosperity trickled down from the top layers of society as might be expected in a market-driven economy. The slaves had more rights than those of the American South; and although not free in the modern sense, women had inheritance rights and were allowed to run businesses, or sign contracts.

Norberg attributes the decline of the Abbasid empire during 11th and 12th Centuries CE to the rise of faith-centric ideals that preached ‘the state and religionwere twins’ and rejected the validity of science. This led to the neglect of intellectual and worldly or material pursuits, ultimately leading to the conquest of much of the Islamic empire by the mighty Mongol Army. The economy took a turn towards a feudalistic system that diminished social respect for the merchants and traders. In fact, this pattern or trend has been observed with some variations during the decline of all golden ages discussed in Norberg’s book, with the notable exception of the current one. He, however, sees similar early-warning-signs of a decay in Anglo sphere-centric Western civilisation at the present juncture.

Although the Muslim golden age unfolded in close proximity to the Europeans or the West, the brilliance of China’s Song Dynasty was almost hidden from them until Marco Polo reached China in late-13th century, when the Song Dynasty was approaching its end. As narrated by Norberg, the Song Dynasty (960-1279) could boast of a “… a dizzyingly free market… [with] wine, grain, cookware, medicine, furniture, fabrics and musical instruments. There were doctors, barbers, monks, millers, metalworkers and carpenters. There were multi-storey restaurants … and evenfood delivery drivers. There were actors, jugglers, servants, scholars, monks and fortune-tellers”. In fact, Song China could develop a version of economic freedom similar to the Greek and Roman experiences. The society enjoyed a degree of laissez-faire liberalism that distinguished it from other contemporary societies. It was not based on an elaborate plan from the top; rather the citizens on the ground played a key role in it. For example, the share of farmers who owned land was around 60 to 70 per cent, which was in sharp contrast to the then Europeans.

The recurring theme in Norberg’s assessment of the Song China and Abbasid Caliphate has been that both had a market for ideas, labour, and capital, which brought freedom and prosperity. Inventions and creativity were democratised, which would have otherwise remained in the hands of a few. Progress, therefore, bubbled up from individuals and small groups of citizens – not from the rulers; and cities were fountains of new ideas leading to innovations and wealth-creation. However, the decays and demise of the golden ages were most often triggered by internal – rather than external – factors.

Norberg holds the view that among the golden ages, the best oneholdingthe highest potential for endurance has been the Anglosphere or the English-speaking civilization since the late 18th Century CE. According to him, the most important achievement of the Anglosphere has been to spread its values and attainments outward across the globe. As a consequence, global extreme poverty could decline from a horrific 38 per cent to only 9 per cent. Norberg concludes, “All the rich and free countries of the world are now part of an extended Anglosphere … The countries might not be English-speaking … but they are all inheritors of Anglo-American ideals … If the United States abandoned its commitment to [them], it is most likely that the remaining countries would work desperately to keep the rest of the order intact”.

Norberg also has some words of caution when he says: “Hard times create strong men – and strong men create harder times”. In the end, the Roman, Abbasid, and Chinese rulers all tried to solve social problems by re-feudalising their economies that tied peasants to the land and replaced commercial relationships with commands. A common sign of a state’s decline was spending more than what was collected as revenue. This led to excessive borrowing and debasement of coins, which triggered soaring inflation and financial chaos. Side by side, international trade was abandoned that originally brought wealth and sparked creativity. Sometimes, trading collapsed when wars made roads and sea-lanes unsafe – as in Rome and during the late-Renaissance. Similarly, the banning of foreign trade by China’s Ming dynasty that succeeded the Song rulers, as well as militarisation of the Roman and Abbasid economies destroyed commerce. These orthodoxies choked off the flow of ideas and solutions that might have aided them in managing the crises. Consequently, the spirit of curiosity, learning, innovation and growth that once made them great was gone.

Dr Helal Uddin Ahmed is a retired Additional Secretary and ex-Editor of Bangladesh Quarterly. hahmed1960@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.