Published :

Updated :

Scientific journals have long been central to the advancement of discovery, defining how knowledge is disseminated, scrutinised, and preserved. From 17th-century pamphlets to contemporary digital platforms, journals have transmitted insights across generations. They serve as channels for new findings, forums for debate, and repositories of enduring knowledge.

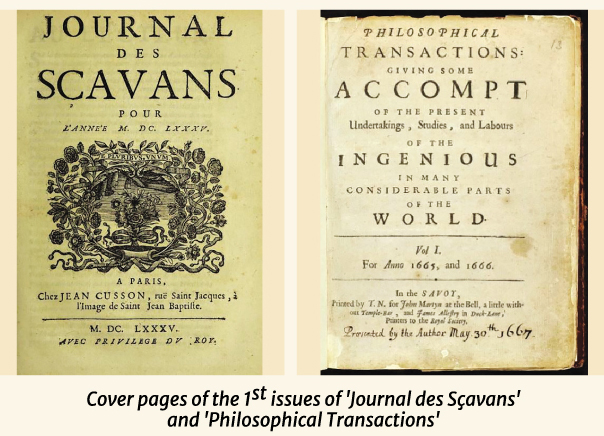

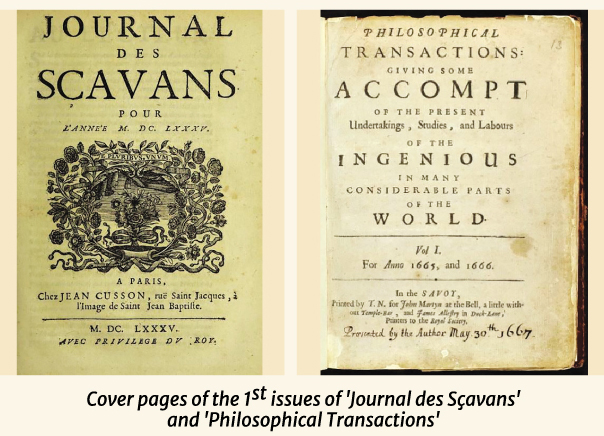

The journey of scientific journals began in 1665, though scholars had long exchanged discoveries through letters and informal networks. On January 5 that year, French scholars released Journal des Sçavans, reviewing developments in science and literature. Just two months later, the Royal Society of London published Philosophical Transactions, now the world’s longest-running scientific journal. At a time when science was only starting to move beyond tradition, these early publications gave discoveries visibility and credibility. Circulation was limited and delivery slow, yet a new era of collective scientific dialogue had begun.

In the 18th century, the hunger for knowledge expanded, and new ways of sharing it emerged. Denis Diderot’s Encyclopédie (1751–1772) tried to assemble all human knowledge into one monumental work. Scientific societies also launched their own journals, such as the Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society (1743) and the Transactions of the Linnean Society of London (1791). These publications made it easier to share discoveries systematically and helped establish fields like chemistry, botany, and natural philosophy.

The 19th century saw rapid growth in scientific publishing, fuelled by industrial progress and expanding knowledge. Professional societies led this expansion, with the Royal Society of Chemistry (1841), the Institute of Physics (1874), the American Chemical Society (1876), and the American Physical Society (1899) publishing journals that emphasised integrity, rigorous peer review, and high standards—principles that still define credible publishing. Building on these efforts, landmark journals such as Nature (1869) and Science (1880) became trusted platforms for researchers and curious readers alike. As scientific fields diversified in the 20th century, new professional organisations emerged to support them. In 1963, the merger of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers and the Institute of Radio Engineers formed the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), highlighting the growing influence of professional organizations in shaping research and publishing.

The 20th century also transformed scientific publishing through new technologies. Digital printing, photocopying, and eventually the internet revolutionised how articles were produced and shared, making journals that once arrived slowly by post instantly accessible worldwide. Databases like PubMed and Google Scholar allowed researchers to locate articles in seconds, while peer review became faster and more organised. At the same time, publishing became a global industry. Companies such as Elsevier, founded in 1947, expanded rapidly, often raising subscription costs and limiting access for smaller institutions, particularly in developing countries.

As traditional publishing became increasingly commercialised, the 1990s and 2000s saw the rise of open-access publishing, making scientific articles freely available online. Authors or their institutions paid publication fees, aiming to broaden access to knowledge. Early examples included Postmodern Culture (1990) and the Public Library of Science (PLOS, 2003). MDPI, founded in Switzerland in 1996, also pioneered open-access journals. This model helped democratise knowledge, but it also introduced commercialisation. High publication fees could strain researchers’ budgets, and some publishers began prioritising profit over quality.

However, the commercialisation of publishing and the rise of open-access models also introduced new challenges for researchers. Commercial pressures fuelled the rise of predatory journals—outlets that cut corners to maximise revenue. These journals often skip peer review, use aggressive marketing, and appear in unreliable indexes. Publishing in such outlets can damage a researcher’s reputation and pollute the scientific record. Poorly vetted studies may be cited, mislead future research, or even influence policy and public understanding. For early-career scientists, the risks are especially high.

Spotting predatory journals is not always easy. Lists and databases often fall short, and a global study by the InterAcademy Partnership concluded that classifying journals as simply predatory or not is often imprecise. Researchers must stay vigilant, assess journals carefully, and exercise informed judgment before submitting work.

The challenges of predatory publishing and commercialisation highlight the need for integrity more than ever. Issues around peer review, open access, data sharing, and research ethics will continue to shape the future of scientific publishing. Tools like indexing databases, evaluation checklists, and community-driven resources can help. Yet the most reliable defence remains thoughtful human judgment—guided by integrity, accuracy, and a commitment to truth.

From the first pamphlets of 1665 to today’s digital platforms, scientific journals have been crucially instrumental in the advancement of discovery. They share breakthroughs, spark debate, and preserve knowledge for future generations, ensuring that science remains trustworthy despite numerous challenges. As discoveries continue, journals—whether in print or online—will remain guiding lights in the pursuit of understanding, upholding knowledge as both a human achievement and a shared responsibility.

Dr. Mohammed Abdul Basith, Professor of Physics at BUET,. is the Founder and Principal Investigator of the Nanotechnology Research Laboratory. m.basith75@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.