Published :

Updated :

The partition of the Indian Subcontinent 70 years ago, when the British rule ended in August 1947, has generated much interest in the American and British press and television recently. Surprisingly, there has not been any significant discussion on the matter in Bangladesh.

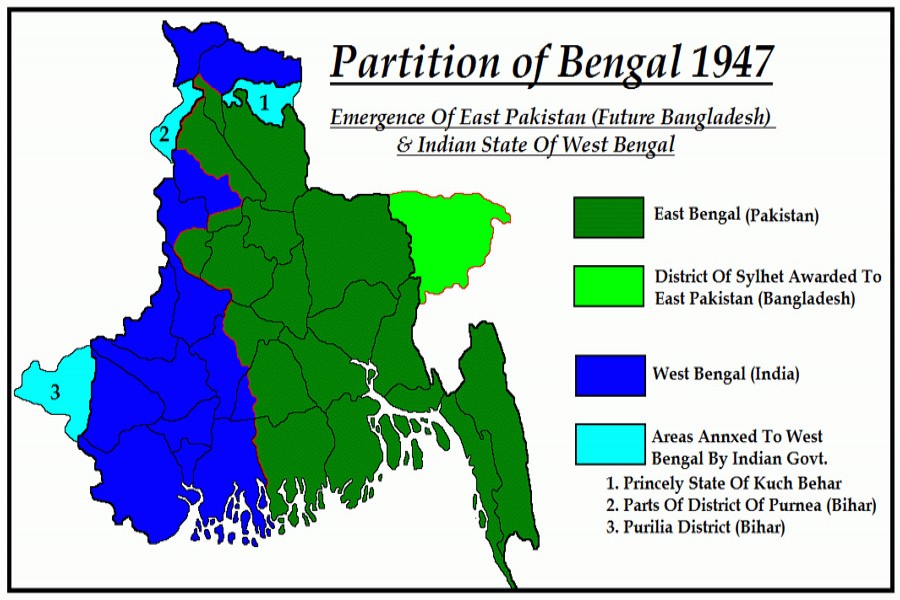

The partition was based on two-nation theory that Muslims and Hindus are two distinct nations. It was the August 1946 Calcutta Hindu-Muslim communal riots I was a witness to as a boy of 12 years of age. The partition also marked a watershed in changing for the better landscape in the life of Muslims in East Bengal, now Bangladesh.

The life sketch of my late father born in a poor impoverished cultivator's family vividly illustrates the condition of Muslims in pre-partition Muslim majority East Bengal. The Muslims then were mostly cultivators' class deprived of opportunities like education, jobs, health care, hygiene and housing. Whatever social opportunities were available were confined to the Hindus nourished and patronised by the British who believed in 'divide and rule'. They constituted what was known as Hindu bhadralok community of lawyers, doctors, teachers, writers, businessmen and government officials. The Muslims suffering from neglect, destitution, exclusion and perpetual pain of debt burden were literally the hewers of wood and drawers of water for the Hindu landed gentry.

In our village, my father was the first Muslim who had completed his graduate studies with distinction by sheer determination and tenacity of purpose overcoming daunting circumstances, mostly of financial distress. He walked 10 miles each day back and forth from his home to his school and college. He defrayed the expense of his education by engaging in private tuition of boys and girls. Pressed by poverty, he abandoned hope of higher studies and in order to be able to support grandpa's family of nine children he looked for a job. But in those days it was not easy for Muslims to find a job without influence. Muslims then were virtually in a state of social segregation and apartheid.

Forlorn and depressed, he one day showed up at a recruiting centre in police lines in district town of Comilla. He was offered the job of literate constable, the lowest rung in the police department. He had no choice. Starvation was staring in the face of his family. He accepted the job. That was in 1927 and he languished for 20 years in subordinate positions as assistant sub-inspector of police, sub-inspector of police and police inspector until partition in August 1947 when he was promoted as deputy superintendent of police and moved from Calcutta to Dhaka, the provincial capital of then East Bengal.

Even after partition Dhaka witnessed in 1947 intermittent communal riots between Hindus and Muslims. Concerned about our security, my father sent me and my elder brother to Brahmanbaria, our sub-divisional home town, for admission in Annada High School, reputed for academic excellence. The tough and taciturn-looking headmaster Binod Behari Dev with a pugnacious moustache said in a gruff voice that there was no seat vacant in his school and advised us to seek admission to George High School or Edward High School. Later we discovered that the school was exclusively for Hindus. My father was adamant. We were finally admitted due to his insistent personal interest and intervention of local authorities. In the evening when I moved about in the town, I noticed that there was no sign of significant Muslim presence in the society.

I had the same experience in 1951 when I moved for my college education to Faridpur, a district town where my father was posted. In Rajendra College, with the solitary exception of one who taught Urdu and Arabic, there was no Muslim professor in faculties. The names of all doctors, lawyers and shops in the town bore distinctly Hindu names. As a child, I imagined in my naivete that Hindus were a superior race and Muslims lacked merit and talent. Hence they were left out of the loop of privileges. It was only later when I grew up I realised that the causes of backwardness of Muslims were discrimination and lack of economic opportunities to them.

Years later in 1980 when I was serving as a first secretary in our diplomatic mission in Calcutta, I went to see Annada Shankar Roy, a noted Bengali writer and a former officer of the Indian civil service (ICS), the administrative arm of the British Raj. He looked at my visiting card with a murmuring demur. He said that it was unfortunate for him to remain alive to see a Bengali introducing himself as a diplomat of a foreign country. I could not help retorting that the blame for partition was generally attributed to exploitation of Muslims by the Hindus who treated Muslims most unfairly, as untouchable underlings like Harijans and scheduled castes. He looked at me with a grimace on his face. It was clear he was not prepared for such a blunt unpleasant truth.

During the remaining nine years of his career after partition, my father received two promotions as Additional Superintendent of Police and Superintendent of Police in quick succession. After retirement, he built a house at Dhanmondi, a posh residential area in Dhaka. He raised his children with the best education opportunities he could afford. Four of his sons received higher education in the USA and England and held important positions in academic careers and government jobs. One of his sons is a renowned spine surgeon in England. All his three daughters are college graduates happily settled in life.

Thus we were no longer a downtrodden class of poor peasants steeped in the stranglehold of grinding poverty, deprivation and ignorance. Now we climbed the social ladder of much vaunted educated, professional rarified middle class. The social transformation of our lives from rural folks to urban elite in course of less than 15 years of partition, even within the limits of disparity and discrimination under Pakistan colonial rule, was nothing short of a miracle. It was apparent the partition helped social mobility of Muslims of East Bengal.

The success story of my father and our family, typical of rise of many more similar Muslim families, would have remained a far cry, a distant mirage without partition of the Subcontinent and Bengal. It is true the aftermath of partition left in its trail an enduring sad and deep scar of dispossession, displacement and bloodletting of both the communities. But it is equally true that it ushered in unprecedented opportunities for Muslims in East Bengal free from the Hindu upper class domination. This is often the missing narrative to many in the new generation in Bangladesh, unfolding the gains of partition for Muslims in East Bengal.

The writer is a columnist and former diplomat.

hannanabd@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.