Innovation or stagnation

The 2025 Economics Nobel & future of developing economies

Published :

Updated :

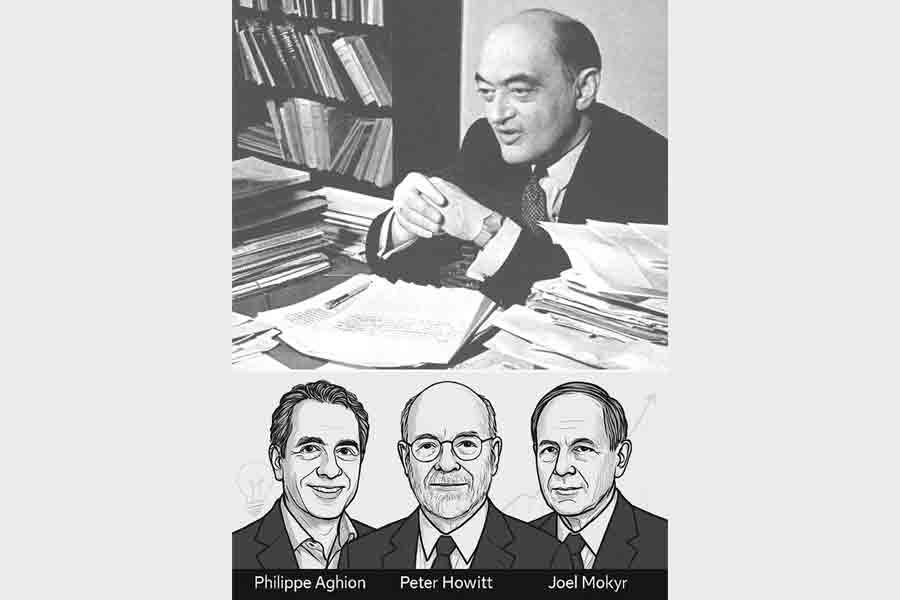

This year’s Nobel Prize in Economics awarded to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt signifies recognition of substantial advancements in the field of innovation-driven economic growth. Their research is anchored in the concept of creative destruction, a theoretical framework first articulated by Joseph Schumpeter, a Harvard professor whose influence persists across generations of economists and scholars.

Schumpeter’s theory of creative destruction says that economic development, capitalist evolution, and technological progress materialise through a perpetual cycle of replacement, whereby emergent technologies, products, institutions, and business models supersede those that are obsolete. Central to this theoretical construct is the entrepreneur, whom Schumpeter identifies as the principal agent of innovation. Entrepreneurs disrupt entrenched structures and reallocate resources toward more productive uses, thereby catalysing economic transformation.

Schumpeter described capitalism as a system driven by constant change, where old industries fade, new ones emerge, and economic methods keep evolving. This process fuels innovation but also brings disruption—causing instability, job losses, and resistance from those who benefit from the old order. Similar patterns can be seen in today’s Bangladeshi economy.

In his seminal work, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, Schumpeter elaborated upon the mechanisms through which capitalism may ultimately undermine itself. He theorised that the socio-psychological underpinnings of capitalism would gradually erode, culminating in the system’s eventual dissolution—a perspective that exhibits conceptual resonance with Karl Marx,. Specifically, Schumpeter contended that institutional inertia, bureaucratic expansion, and entrenched interests hinder adaptive change, and predicted that bureaucratisation would supplant entrepreneurial vigour, thereby diminishing innovation. He further anticipated that pronounced inequality would incite public resistance, engendering expanded state intervention and regulatory frameworks, and thus precipitating the demise of capitalism.

For Schumpeter, the principal challenge lies in sustaining the dynamism of innovation while judiciously managing its destructive externalities. He regarded the eventual decline of capitalism as an inevitable, though undesirable, outcome.

Regarding socialism, Schumpeter did not support Marxian revolutionary communism; instead, he predicted that the instability generated by creative destruction, coupled with democratic and bureaucratic evolution, would facilitate a gradual and peaceful transition to a form of socialism. Nevertheless, he was sceptical about socialism’s capacity for innovation, arguing that the absence of entrepreneurial incentives would impede the system’s creative potential.

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics was conferred in recognition of research elucidating the mechanisms underpinning innovation-driven economic growth. Joel Mokyr identified the prerequisites for sustained technological advancement, demonstrating how creative destruction is contingent upon specific cultural, social, and institutional conditions. Mokyr emphasised the necessity of a knowledge-oriented culture, institutions that promote the free exchange of ideas, and a societal disposition conducive to risk-taking. Absent these factors, innovation is liable to stagnate.

Aghion and Howitt advanced Schumpeterian theory by constructing formal, analytically robust models that explicate how endogenous innovation engenders sustained economic growth. Their framework delineates the displacement of established institutions, the role of competition in stimulating innovation, and the influence of policy, institutional architecture, and market structure on economic dynamism. The central thesis posits that growth is the product of a continuous, self-renewing cycle of innovation and obsolescence.

The Royal Swedish Academy honoured the three economists “for explaining innovation-driven economic growth.” In its statement, the Academy stressed that economic growth is never automatic — it demands constant effort — and warned that “to prevent stagnation, the forces behind creative destruction must be kept alive.” Their collective research shows how new ideas, products, and discoveries can accelerate growth.

To appreciate the full importance of this Nobel-winning work, it must be viewed in relation to Schumpeter’s original theory. Schumpeter’s ideas were largely philosophical and conceptual. Aghion and Howitt transformed them into a formal mathematical model, enabling empirical and quantitative analysis. Mokyr complemented this by providing historical and institutional context, examining the long-term cultural, social, and scientific foundations that sustain innovation and make creative destruction possible.

The recent research deepens our understanding of which policies effectively promote innovation and what trade-offs they entail — such as how to maintain competition, design patent systems, overcome resistance from established firms, and ensure that institutions stay receptive to new ideas. In this respect, their work significantly extends Schumpeter’s original theory.

They also connected Schumpeter’s concepts to modern issues like globalisation, trade, openness, and the risk of economic stagnation. The 2025 Nobel laureates’ contributions shed light on why some economies, even with access to advanced technology, struggle to innovate or experience prolonged stagnation.

The landmark 1992 paper by Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt, “A Model of Growth through Creative Destruction,” marked the foundation of modern Schumpeterian growth theory. It translated Schumpeter’s qualitative insights into a formal theoretical framework, showing that economic growth emerges from a continuous cycle of innovation in which new products and processes replace out dated and inefficient ones.

Earlier exogenous growth models treated technological progress as something that occurred outside the economic system. Aghion and Howitt, however, made it an internal—or endogenous—process, driven by purposeful actions and incentives. Firms invest in research and development to gain temporary monopoly advantages, but as better technologies emerge, older ones are displaced. Growth, therefore, results from on-going competition among innovators — a relentless race in which individual success is fleeting, yet society as a whole advances.

While Aghion and Howitt explained the mechanics of innovation through formal modeling, economic historian Joel Mokyr examined its underlying spirit. In his influential works The Lever of Riches and A Culture of Growth, Mokyr posed two fundamental questions: Why did the Industrial Revolution begin in Europe, and why did it persist? After extensive research, he concluded that the revolution was not merely economic or technological—it was intellectual and cultural.

Mokyr argued that Europe’s transformation was born from a distinct cultural and intellectual climate that celebrated curiosity, experimentation, and rational inquiry. The “Republic of Letters”—a transnational community of scholars, scientists, and inventors—enabled knowledge to circulate freely across borders. This openness fostered what Mokyr terms the “Industrial Enlightenment,” an era in which scientific progress and technological innovation became mutually reinforcing.

For Mokyr, innovation is more than an economic process — it is a cultural institution. Progress thrives when societies value fresh ideas and accept the risks that come with them. But when imitation, censorship, or fear of failure dominate, creativity withers. His work offers a timeless lesson: sustainable growth requires more than capital and labour — it also depends on a vibrant culture of freedom, trust, and intellectual openness.

What lessons should the developing countries like Bangladesh extract from the theories of this year’s Nobel Laureates? Bangladesh’s garment industry has long been the foundation of its industrial success. Yet, to stay competitive, it must increasingly embrace automation, design innovation, and environmentally responsible production. Likewise, the expansion of Bangladesh’s digital economy — from e-commerce to IT services — hinges on empowering young entrepreneurs to think creatively and innovate.

Bangladesh’s growth model, built on low-cost labour and export-led production, has achieved remarkable progress but cannot endure forever. The next phase of development must focus on innovation-driven growth — one that rests not only on physical infrastructure, but also on cultivating an environment where creativity, experimentation, and entrepreneurship can truly thrive.

Dr N N Tarun Chakravorty is a Professor of Economics at Independent University, Bangladesh. Editor-At-Large, South Asia Journal. nntarun@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.