To defer or to leap, that is the question

Bangladesh's graduation from LDC category

Published :

Updated :

In 2026, Bangladesh is expected to graduate from the United Nations (UN)’s list of Least Developed Countries (LDCs). Some view this as a triumph, while others see it as a threat. The truth lies in between: graduation is neither a silver medal of development, nor a sentence of economic hardship. It is a transition—one that Bangladesh must manage carefully.

Graduation is a badge of honor, reflecting decades of progress in growth, poverty reduction, and human development. Yet it also provokes anxiety: the loss of duty-free trade preferences, concessional loans, and intellectual property flexibilities that have long cushioned Bangladesh’s rise. The real debate is not about whether graduation is desirable, but about timing and preparedness. Deferment is possible, as history shows, but even if it does not occur, graduation need not be a catastrophe. With foresight and reform, it can be managed as an adjustment—not a downfall.

Deferring graduation is neither automatic nor politically costless. A formal request must be made—either to the Chair of the UN Committee for Development Policy (CDP) or directly to the UN Secretary-General. In both cases, the applicant must demonstrate that unforeseen and extraordinary events beyond its control have derailed development progress. In the past, civil conflict, natural disasters, and sharp economic shocks such as collapsing commodity prices have been accepted as grounds.

To succeed, such a request must be carefully argued, supported by evidence, and reinforced by diplomatic effort. It also requires approval by a simple majority at the UN General Assembly. Bangladesh’s international standing makes this feasible, but the backing of influential member states would be helpful. Moreover, under the Enhanced Monitoring Mechanism (EMM), graduating countries are subject to ongoing oversight and annual reporting, underscoring that deferment is neither trivial nor automatic, but rather a laborious exercise in diplomacy and persuasion.

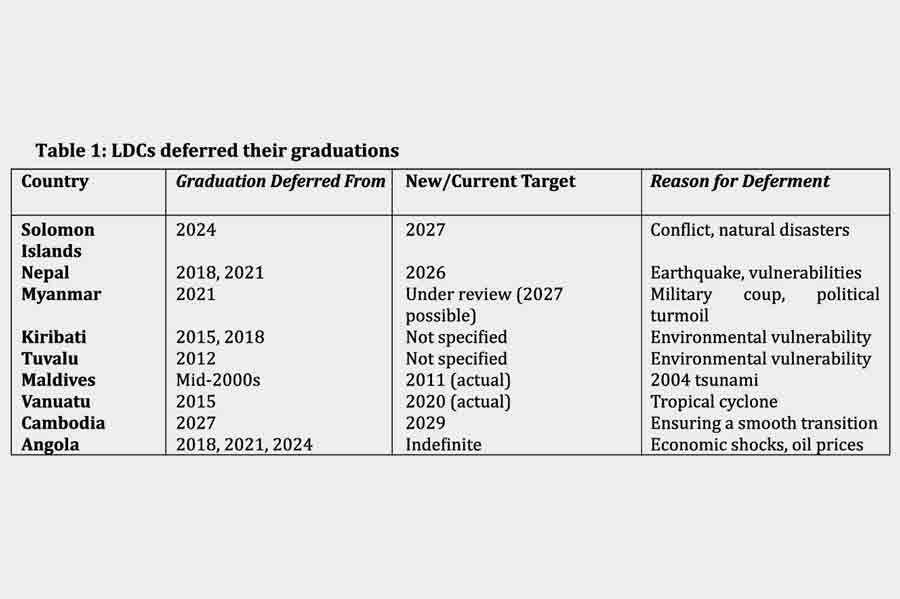

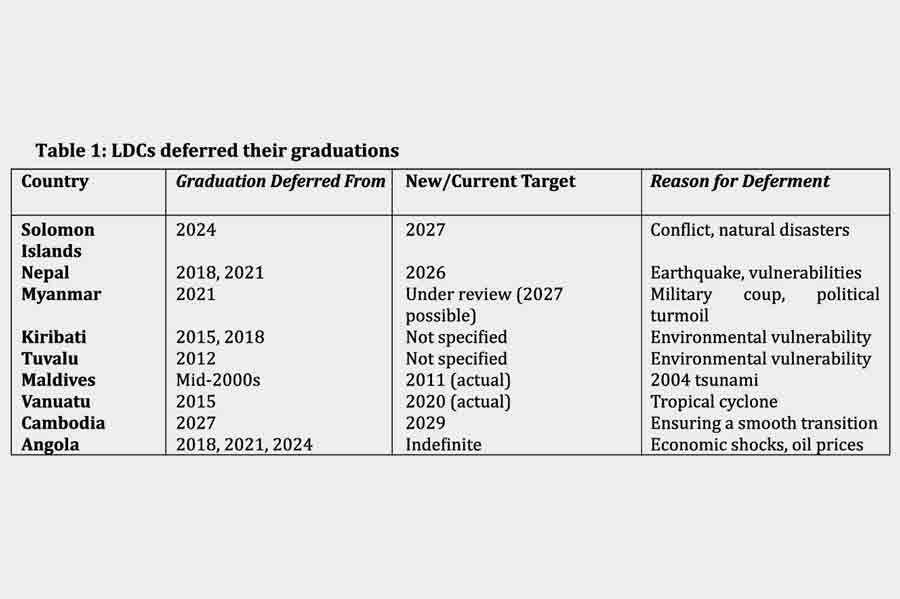

History shows that deferment is not unusual (see the table below). Several countries have adjusted their graduation timelines in response to shocks or vulnerabilities. Nepal has postponed graduation twice due to earthquakes and other vulnerabilities. The Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, the Maldives, and others have also delayed their graduations in response to crises. Tuvalu, with a higher per capita income than Bangladesh, has deferred indefinitely. With a well-prepared case and diplomatic support, Bangladesh could do the same. Without it, the country must brace for the consequences of graduation.

Trade Impacts – The Loss of Duty-Free Privileges: After November 2026, automatic duty-free quota-free (DFQF) privileges will expire in most major markets. However, Bangladesh will continue to enjoy a guaranteed three-year transition period until 2029 in the European Union (EU) and the United Kingdom (UK), during which current duty-free benefits remain in place. This cushion gives exporters some breathing space, but it is temporary. Beyond 2029, Bangladesh will need to qualify for stricter regimes such as the EU’s GSP-plus, which requires compliance with tough labor, environmental, and governance standards. Meeting these conditions will demand reforms that could strain industries already under pressure. China has also signaled that it may maintain DFQF access for a transitional period, though this, too, is temporary.

A paradox underscores Bangladesh’s resilience: the United States, its single largest export destination, provides no LDC-specific trade privileges. Despite facing normal tariffs, Bangladesh has established a thriving market presence in the country, primarily due to its garment industry. This indicates that while the loss of DFQF access in some markets will be a setback, Bangladesh can still compete in non-preferential markets—provided it strengthens its domestic competitiveness.

Foreign Assistance – No Direct Link to LDC Graduation: Unlike trade, foreign assistance is not tied directly to LDC status. Concessionality primarily depends on per capita income, rather than UN classification. As Bangladesh’s income has risen, the World Bank and Asian Development Bank have already reduced the “soft” element of their lending, shifting to harder terms with fewer grants.

Other institutions, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), were never concessional to begin with. Similarly, the Islamic Development Bank (IsDB) and other Islamic finance sources base their terms on project viability, creditworthiness, and income levels, rather than LDC status.

Crucially, Bangladesh continues to qualify for concessional support from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Eligibility for the IMF’s low-income facilities depends not only on income but also on debt vulnerabilities and market access. According to IMF Executive Board documents (2025), Bangladesh remains eligible for the Extended Credit Facility (ECF), Extended Fund Facility (EFF), and Resilience and Sustainability Facility (RSF). These programs remain concessional because, despite higher incomes, Bangladesh continues to face structural vulnerabilities and lacks full access to international capital markets.

Thus, graduation from LDC status will not sharply alter aid or concessional finance. The true determinants remain income growth, debt sustainability, and market access.

Foreign Investment – Opportunities with Risks: In theory, graduation could signal stability and progress to global investors. Yet the reality is more nuanced. If the loss of trade preferences weakens exports, Bangladesh could become less attractive for export-oriented foreign direct investment (FDI).

Private investors, however, pay little attention to LDC status. They base their decisions on fundamentals, including per capita income, creditworthiness, governance, political stability, and market potential. Bangladesh’s ability to attract FDI will depend more on how it manages these fundamentals than on its UN classification.

By contrast, government-backed finance—such as loans under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—often carries some concessional elements and is relatively insensitive to LDC graduation. Unless Bangladesh’s income rises significantly, the concessionality of these flows is unlikely to be affected.

Intellectual Property Rights – A Transition, Not a Shock: Bangladesh’s graduation from LDC status in 2026 will not immediately overturn its intellectual property regime, but the broad exemptions it currently enjoys will begin to narrow. Currently, as an LDC, Bangladesh is exempt from enforcing key provisions of the WTO’s TRIPS agreement—especially those related to pharmaceuticals—under a special waiver that remains in effect until 2034. However, this waiver only applies to countries that remain LDCs. Once Bangladesh graduates, it will lose that blanket exemption and must begin aligning its laws with global standards.

The oft-cited “three-year transition until 2029” does not apply to patents or intellectual property. On IPR, Bangladesh will face an earlier adjustment: after 2026, it will need to start phasing in TRIPS obligations. That said, as a developing country, it will still retain important flexibilities—such as compulsory licensing (TRIPS Article 31) and parallel imports—which, while narrower than the broad LDC waiver, can help soften the impact.

The real task is to use the remaining years before 2026 to strengthen legal and institutional capacity, prepare the pharmaceutical sector for stricter rules, and diversify into industries less vulnerable to patent restrictions. [Note: The discussion of WTO/TRIPS provisions in this article reflects the author’s understanding as an economist. It should not be taken as legal advice; readers are encouraged to consult specialised legal sources for authoritative interpretation.]

Conclusion – A Question of Choice: To defer or to leap—that remains Bangladesh’s central question. Precedent shows deferment is possible when shocks strike. But even if deferment proves elusive, graduation is not a Shakespearean tragedy. It is a matter of reform and adjustment.

Yes, there will be bumps—tariffs here, tougher standards there, and eventually stricter patent rules. Yet, Bangladesh has already demonstrated its ability to thrive in demanding markets, including the United States (US), without special preferences. Concessional finance will not disappear; it will simply become less soft as incomes rise. And while Bangladesh will retain three years of trade preferences until 2029, this cushion does not extend to intellectual property. Regarding patents, TRIPS obligations will take effect immediately after graduation, although developing-country flexibilities provide room for adaptation.

In the end, LDC graduation is less a question of to be or not to be than of how to be—how to reform, compete, and adapt. With foresight and pragmatism, Bangladesh can turn graduation from a cliffhanger into the next chapter of its growth story.

Dr MG Quibria is an economist with extensive experience in international development and academia, having held senior roles at the Asian Development Bank and the Asian Development Bank Institute. He has been a professor and visiting scholar at institutions across three continents. mgquibria.morgan@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.