Published :

Updated :

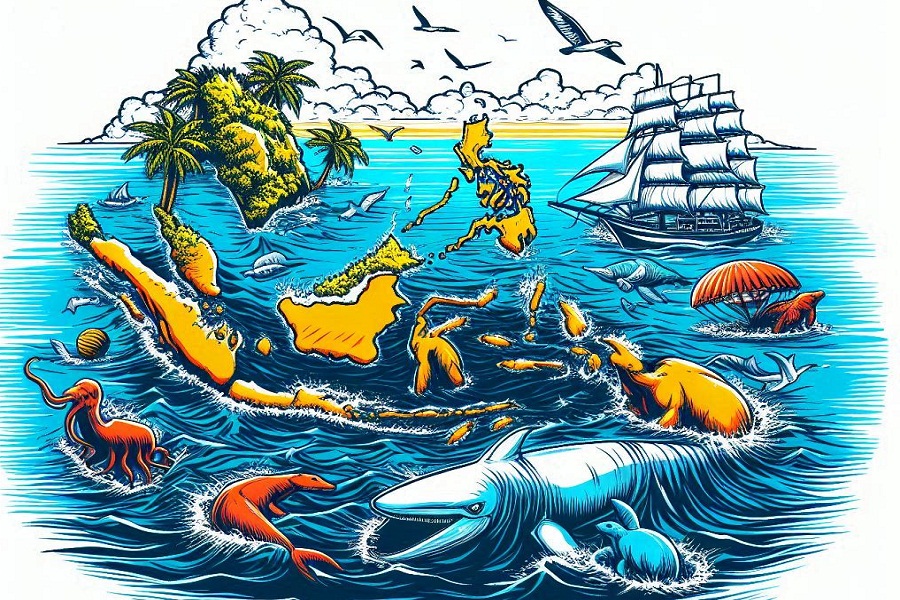

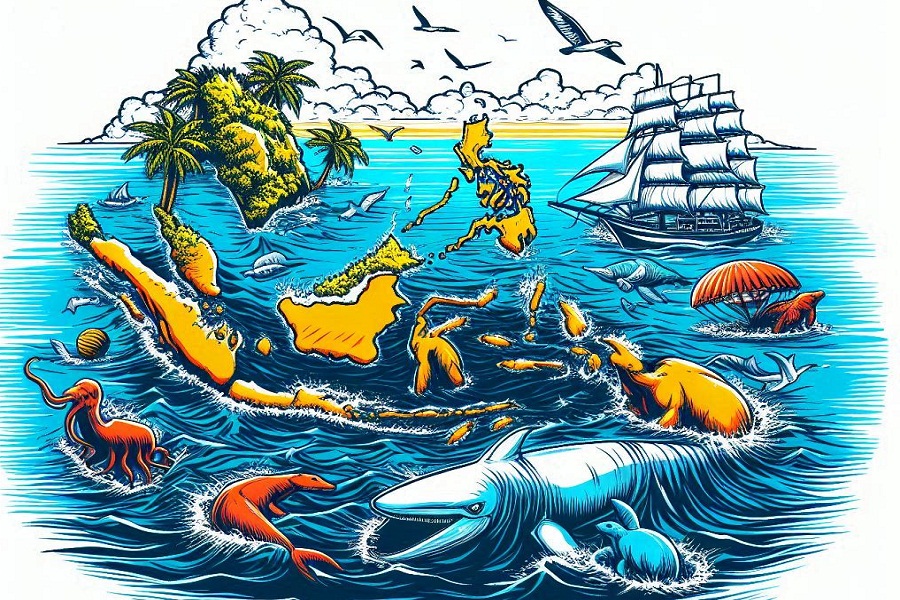

There is a mysterious line between the two islands of Indonesia, both tangible and intangible. It's a paradox-you can't see it, yet it's undeniably there. Imagine standing on the coast of Bali, gazing east to the shores of Lombok. You're peering directly at the line's narrowest point, a seemingly unremarkable 32 km stretch of water. This enigmatic barrier winds through the entire Malay Archipelago, the world's most extensive collection of islands. On the western side of the line, the animal kingdom reflects Asia, with its iconic rhinos, elephants, tigers, and woodpeckers. The eastern islands boast a different ecological character, home to unique species such as marsupials, Komodo dragons, cockatoos, and honeyeaters.

Scientists call this a biogeographic boundary, the sharpest and most iconic named 'Wallace line'.

How did this invisible line come to be?

Wallace first sketched the Wallace line in 1859. Alfred Russel Wallace was a British naturalist you might have heard of as the co-discoverer of natural selection.

This concept came to him in a literal fever dream as he lay bedridden with malaria during part of his eight-year trip around the Malay Archipelago. While he ended up being overshadowed by Darwin on that front, the second best idea he had on that trip was the existence of the Wallace line.

This idea helped to establish him as the father of biogeography, the study of the distribution of living things.

He first noticed something intriguing as he moved east from Bali to Lombok. Wallace saw the differences in animal life between the two as even more striking than between England and Japan.

Birds initially caught his attention; certain species plentiful in Java and Bali, like the yellow-headed weaver, coppersmith barbet, and the Javanese three-toed woodpecker, didn't exist in Lombok.

This abrupt shift extended to mammals and even many insects, almost like an invisible barrier separating two worlds.

Wallace realized that the geological past shapes the biological present. He concluded that the Western islands must have once been connected to the Asian mainland, while today they're surrounded by shallow seas; this is only the result of a geologically recent rise in sea levels.

Wallace had a hunch that throughout that change, deeper waters with strong currents between the two regions must have prevented many species from crossing from continent to continent when sea levels were lower, and this is still preventing many species from crossing today when sea levels are higher.

How can the Wallace line be both real and imaginary?

The planet's surface is dynamic. It comprises large sections or plates that move and collide over vast stretches of geologic time. The Malay Archipelago is one of the world's most complex tectonic regions, a meeting point of multiple plates jostling for space.

Today, we know them as the Paleo Continents of Sunda in the west and Sahul in the east, both of which existed during the ice ages when more water was locked up in ice and sea levels were lower.

The Sahul continent on the eastern side of the line encompassed Australia, Tasmania, New Guinea, and the Aru Islands. It only approached the Asian Sunda continental shelf in the west around 20 to 25 million years ago, in the late Oligocene or early Miocene epoch.

This resulted from the Australian Plate slowly drifting north over tens of millions of years after breaking away from Antarctica in the south, bringing its distinctive community of birds, reptiles and marsupials.

Why does it shape the distribution of so many species?

The Wallace Line acted as a barrier to Asian species moving east. For example, Komodo dragons today live on several islands in eastern Indonesia. Their fossils first appeared in mainland Australia more than 3 million years ago.

Wallace's invisible line may not be accurate in a physical sense. Still, it shows how loudly ancient geological events can echo through time and how they shape the diversity and distribution of life in strange and contrasting ways. And while Darwin might get virtually all the credit as the guy who figured out how species came to be, Wallace is still recognized as a pioneer in figuring out how species came to be where they are.

nidrisanan7314@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.