Draft renewable energy policy 2025 falls short of means to attain targets

Published :

Updated :

Bangladesh's draft renewable energy policy 2025 has come under heavy scrutiny from energy and climate experts who say it lacks a clear roadmap and coherent direction to meet renewable energy targets.

The policy, which took more than four years for drafting, was made available for public consultation for just 21 days through February 24 this year.

Civil society groups, analysts, and sector stakeholders, who were largely left out of the formulation process, say the draft policy, without critical revision, may fail to steer the country towards clean energy goals as the previous policies did.

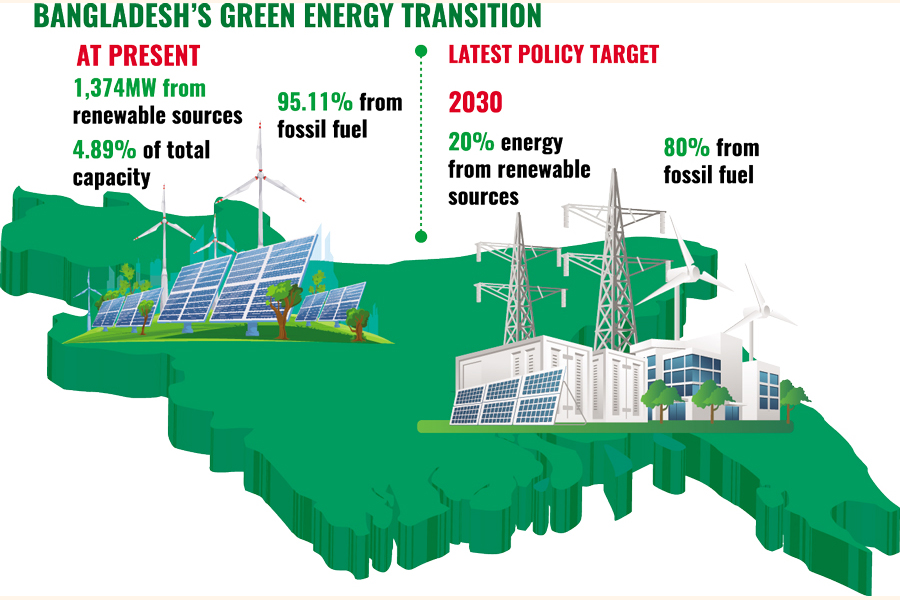

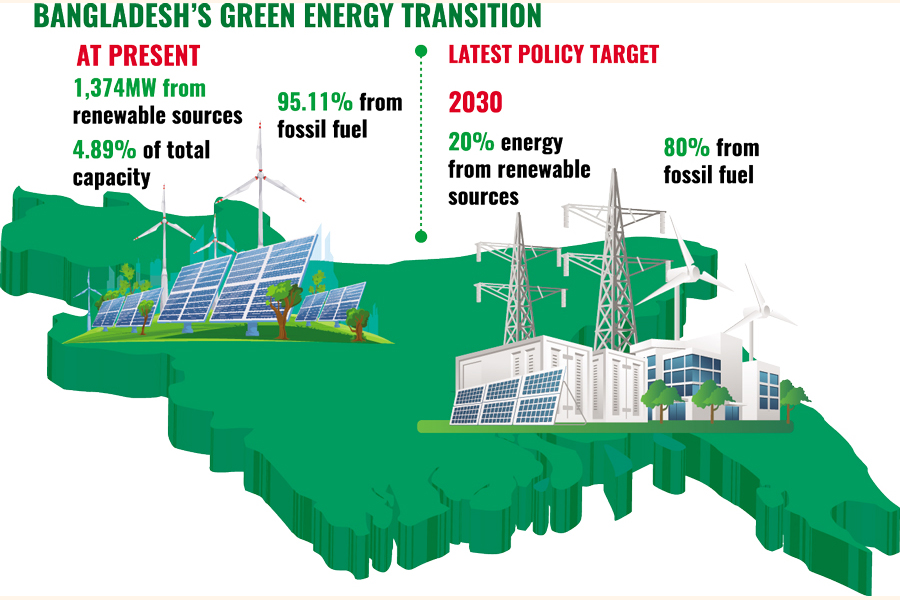

The draft policy sets new renewable energy targets -- 6,145 MW, 20 per cent of the country's total power generation capacity, by 2030; and 17,470 MW, 30 per cent of the capacity, by 2041.

The targets are less ambitious than earlier pledges, but they are based on installed capacity, not actual power generation, raising concerns about the effectiveness of the 2025 policy in driving a real energy transition.

"Installed capacity doesn't reflect the actual contribution of renewables to the grid," said Hasan Mehedi of the Coastal Livelihood and Environmental Action Network (CLEAN).

"We need generation-based targets backed by annual and five-year roadmaps, which the draft policy completely lacks," he said.

Mr Mehedi also questioned how the government could propose a new policy without analysing the repeated failures of the past ones.

For example, under the Mujib Climate Prosperity Plan (2022-2041), presented at COP26, Bangladesh pledged to produce between 6,000MW and 16,000MW of renewable energy by 2030.

However, since the country's first solar plant became operational in 2017, only 1,374.35MW has been added from renewable sources, both on-grid and off-grid, which constitutes only 4.89 per cent of the total power generation capacity.

Solar accounts for 1,080MW, followed by 230MW from hydropower and 62.82MW from other sources, such as wind, biomass, and biogas, according to the National Renewable Energy Database of the Sustainable and Renewable Energy Development Authority (SREDA).

The first renewable energy policy, formulated in 2008, was aimed at achieving 5 per cent renewable energy by 2015 and 10 per cent by 2020. Then the 7th five-year plan was drawn to attain 10 per cent renewable energy by FY21.

Neither of the policies witnessed any success.

Later on, the 8th five-year plan set a target to reach 10 per cent energy generation from renewable sources. That failed too.

The 2025 policy, if finalised, would require Bangladesh to add at least 4,626 MW more renewable energy in five years, a feat experts believe is unachievable without a robust and clearly defined plan.

Experts also worry that the 2025 draft policy is not in alignment with other national and international commitments, including the Bangladesh Delta Plan (BDP), Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC), Mujib Climate Prosperity Plan, and the Integrated Energy and Power Master Plan (IEPMP).

As Bangladesh prepares to submit its updated NDC-3 and review the IEPMP, the 2025 draft policy offers no explanation as to how it will align with these frameworks.

Khondaker Golam Moazzem, of the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD), noted that formulating such a critical policy in isolation, without engaging key stakeholders, creates inconsistencies and undermines its effectiveness.

He also insisted that expanding renewable energy generation targets without any scheme to reduce dependency on energy from fossil fuels is "impractical".

Unequal incentives, financing gaps

The draft policy grants full tax exemption for 10 years and partial exemption for another five years to companies investing in renewable projects. But individual citizens would not receive any financial support. In fact, ordinary users installing rooftop solar systems still pay taxes ranging from 26-56 per cent on solar accessories.

In contrast, countries like India and Cambodia provide up to 30 per cent direct subsidies for rooftop solar adoption. Although a recent circular from the National Board of Revenue (NBR) announced exemptions from import duties on solar components, policy implementation and accessibility remain unclear.

Limited access to finance also continues to hinder progress in achieving renewable energy targets.

Shafiqul Alam, lead analyst for Bangladesh at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), pointed out that while the Bangladesh Bank has increased the scope of green refinancing schemes from Tk 4 billion to Tk 10 billion, a loan for a solar park cannot exceed Tk 0.3 billion, insufficient for even a modest 10MW solar project.

Mr Alam stressed that Bangladesh must explore multilateral funding, green bonds, and private equity while simplifying approval procedures.

"Financing is the backbone of energy transition," he said, "and we're still far from making that accessible."

Tapping into potential of RMG sector

One of the most promising sectors for renewable energy adoption is the Ready-Made Garment (RMG) industry, which accounts for over 80 percent of the country's exports.

The Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) has already signed the UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) Fashion Industry Charter for Climate Action, aiming to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 30 per cent by 2030.

Yet, actual renewable energy use within the sector remains limited.

Ferdous Ara Begum, chief executive officer of Business Initiative Leading Development (BUILD), noted that most factories have only installed systems of 5 KW capacity, often just to meet requirements set by buyers, not to achieve sustainability. She cited several challenges, including land scarcity, inverter costs, access to green finance, and poor policy implementation.

"With better incentives and infrastructure, the RMG sector could lead the renewable energy transition," she said.

The draft 2025 policy includes some positive steps, such as updating SREDA's net metering guidelines to allow up to 100 per cent of a building's sanctioned load to be met via rooftop solar, up from the current 70 per cent. But without addressing fundamental gaps in planning, coordination, and financing, experts fear the policy will fall far short of what is needed.

The country must ensure that its renewable energy policy is not just a document of intent but a roadmap grounded in reality, supported by robust public engagement, and aligned with long-term climate and development goals.

sumi.drm@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.