Published :

Updated :

Across South Asia and beyond, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are often celebrated as the engines of economic growth. In neighbouring countries, this recognition has translated into real policy action, institutional support, and financial commitment.

Unfortunately, in Bangladesh, the story is more complicated-and far less inspiring.

Take India, for example. The country has a dedicated Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises, which not only protects but actively nurtures small businesses.

Since 1990, the Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI) has operated as a commercial bank, providing focused financial services to the sector.

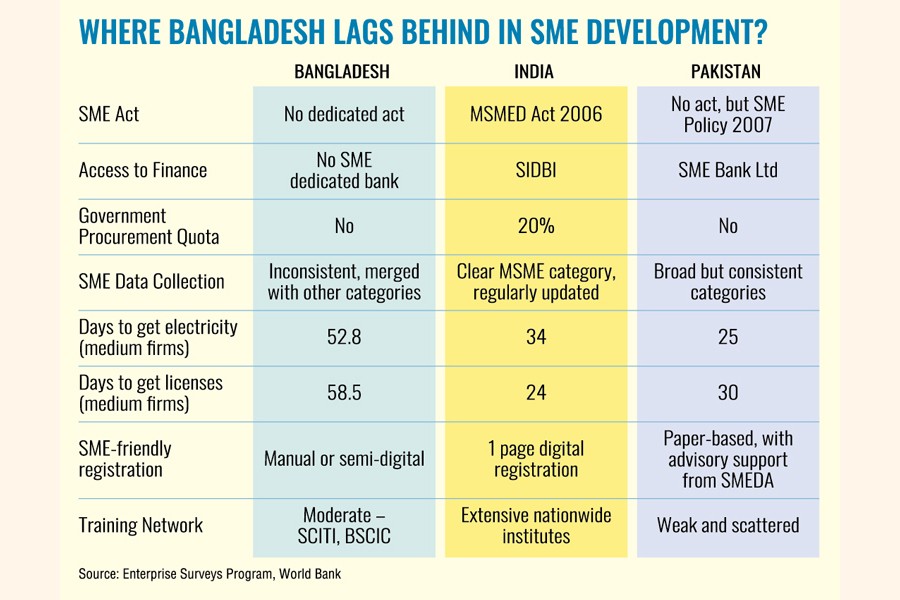

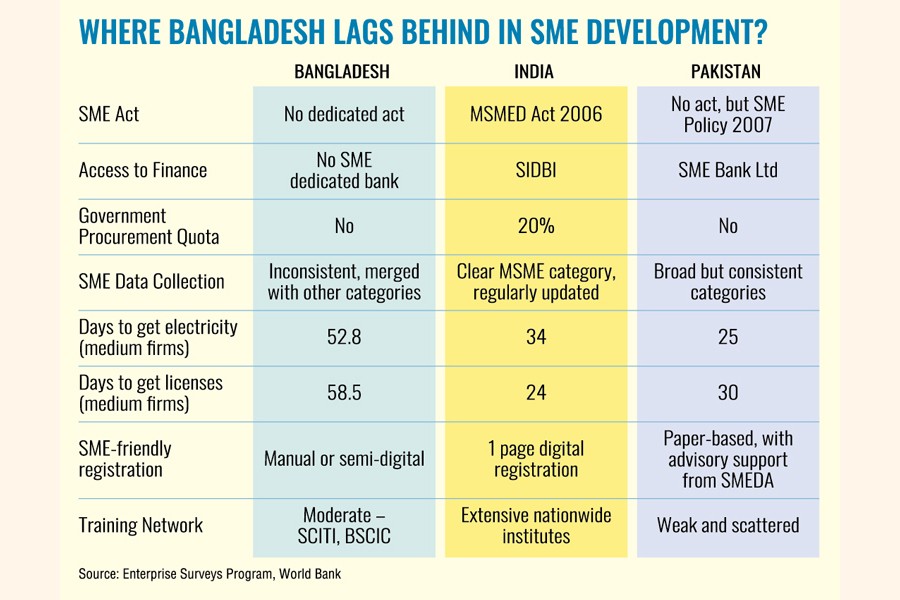

Even Pakistan, despite grappling with many economic challenges, has done more. It runs a dedicated SME Bank and benefits from the work of an independent body -- the Small and Medium Enterprise Development Authority (SMEDA) -- which supports small businesses, even in the absence of a full-fledged ministry.

Bangladesh, in contrast, depends on the SME Foundation (SMEF), a non-profit organisation housed under the Ministry of Industries. It lacks the legal mandate, the resources, and the institutional muscle to support a sector that forms the backbone of the country's industrial employment.

With limited staffing, no banking authority, and virtually no budgetary independence, the SMEF has been left to do much with very little. And the consequences are showing.

Despite SMEs making up roughly 90 per cent of employment in Bangladesh's industrial sector, their contribution to GDP remains disproportionately low.

While India sees its SME sector contributing 45 per cent of GDP, and Pakistan reports about 40 per cent, Bangladesh hovers around 27 to 30 per cent -- and even that figure is uncertain.

That's because the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) doesn't compile SME-specific data when calculating GDP, making it difficult to measure the sector's true impact.

Compare that to global peers: in Vietnam, a key competitor in the global export market, SMEs account for about 45 per cent of GDP.

In Malaysia, it is just over 39 per cent. The figures are even more impressive in powerhouse economies -- 60 per cent in China, 50 per cent in Japan, and 46.9 per cent in South Korea. Even within the European Union, SMEs contribute about 40 per cent to total GDP

Clearly, something is missing in Bangladesh.

Part of the problem is policy inertia. While other countries have passed comprehensive laws or drafted master plans to support SME growth, like India's MSMED Act of 2006, or South Korea's long-standing support via KOSME (Korea SMEs & Startups Agency), Bangladesh is still operating under the SME Policy 2019, which has expired in 2024. And even that policy has remained mostly on paper.

Although the policy announced an ambitious budget of Tk 105.12 billion over five years, the government did not allocate a single taka.

Out of 30 scheduled meetings mandated under the policy -- 10 for a high-level committee led by the Minister of Industries, and 20 for an implementation committee headed by the Industries Secretary -- only nine were held in total. The message is SMEs are not a political or economic priority.

"We are facing serious challenges in financing, skills training, marketing, and diversification," said Anwar Hossain Chowdhury, Managing Director of the SME Foundation.

Speaking to The Financial Express, he acknowledged that the sector's limited contribution to GDP mirrors its lack of support. "We are trying our best," he added, "through training programmes, policy advocacy, and organising SME fairs to promote local products."

But the Foundation is running on fumes. It currently operates with only 80 active staff members, less than half of its approved positions. Most of its funding comes from interest earnings on a Tk 2.0 billion seed fund, and a one-time Tk 3.0 billion Covid-19 stimulus package -- not nearly enough for nationwide impact.

Mr Chowdhury believes that to boost the sector, Bangladesh must go beyond token support.

He recommends establishing a dedicated SME bank to improve access to credit, significantly increasing funds for skills development, and introducing a separate concessional tax regime for small businesses to help them compete with larger firms.

He also advocates for reserving 20 per cent of public procurement for SMEs, mirroring India's affirmative procurement policy.

His concerns are echoed by Dr Mustafa K. Mujeri, former Director General of the Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies (BIDS). "We need a comprehensive master plan," he stressed, proposing a roadmap similar to KOSME's approach in South Korea.

Dr Mujeri also called for a centralised online SME database, linked to unique business IDs, to enable evidence-based policymaking.

He suggested forming a specialised SME finance wing to manage collateral-free loans and credit guarantees, freeing small businesses from the high-risk stigma attached by commercial banks.

For long-term growth, he said, the country should invest in business incubators, in partnership with universities and the private sector, to help startups survive and scale.

He also criticised Dhaka-centric SME programmes, calling for district-level SME zones, based on the super cluster models successfully implemented in China and India.

Perhaps most crucially, Dr Mujeri urged Bangladesh to actively pursue technology transfer and skills partnerships with countries like South Korea and Germany, where SMEs play a dominant role in high-value manufacturing and innovation.

Both experts agree: the SME sector in Bangladesh has enormous potential. It can drive employment, boost exports, and contribute significantly to GDP -- if the right infrastructure, financing, and policy support are put in place.

The question is no longer whether SMEs matter -- they clearly do. The question is whether Bangladesh's policymakers are ready to give them the tools, trust, and institutional support they need to thrive.

Until then, SMEs in Bangladesh will remain underpowered engines of growth -- running hard, but going nowhere fast.

jahid.rn@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.