Published :

Updated :

Kalu Sarder does not exactly know which of his ancestors lived on land. Growing up, he learned from his parents that his forebears were terrestrial inhabitants in the dim and distant past. One of them started living on a boat after losing their house to riverbank erosion, and the descendants followed suit.

"We are boat people. Everything in our lives revolves around our boats. We live on boats day in and day out, rain or shine," Kalu, who lives in the Charmontaz union under Patuakhali's Rangabali upazila, told The Financial Express. Now in his 50s, he remembers spending his childhood on a boat, where his parents also lived. He had this unique upbringing as a Manta child.

Often categorised as Bedes, the Mantas are in fact a floating fishing community mostly living in Bangladesh's southwestern coastal areas, including Barishal, Bhola, and Patuakhali. Their total number is estimated at 0.25-3.0 million. The majority of them have the same story - their forefathers were compelled to adopt the full-fledged boat life after riverbank erosion had devoured whatever land they owned or lived on.

Riverbank erosion is a common phenomenon in Bangladesh, which sits on the world's largest Ganges-Brahmaputra delta and is criss-crossed by around 1,000 rivers. The Centre for Environmental and Geographic Information Services in Dhaka estimates that erosion along the banks of the Jamuna and Padma destroyed 93,965 hectares and 33,585 hectares of land, respectively, between 1973 and 2021. About 3,000 hectares of land erode each year on average, displacing about 25,000 people, according to the National Adaptation Plan of Bangladesh (2023-2050).

Living on a wooden boat is a far cry from doing so on a houseboat. The latter usually offers a range of facilities to ensure comfortable living. But it is more of an endurance test than a pleasant experience for the Mantas to do daily chores, rest, and sleep on the traditional, nondescript rowing boats.

Because of this unusual way of life, they have developed an indissoluble bond with rivers and their water. Their matrimonial bonds are also formed right on the boat, with the child marriage rate remaining high. Kalu arranged a bride for his youngest son from Char Anda, a small island that takes around 15 minutes to reach from Charmontaz by trawler.

Located around 143 nautical miles (265km) from Dhaka in the country's southern reaches and shaped like a tilted potato, Charmontaz is a beautiful island featuring two-storey tin-roofed houses, coconut trees, and watermelon fields. With no urban cacophony, its inhabitants enjoy life in the slow lane and are mostly involved in fishing and agriculture. The chasm between them and the Mantas is that they live in houses, while access to clean water remains a problem for both groups.

Six Manta families first arrived on the shores of Charmontaz in 1985, local journalist and social worker Md Aiub Khan told The Financial Express. Now there are 160 families and 100 of them live permanently, while the rest move around and moor where the fish stocks are abundant, depending on the season. For example, they fish in Patuakhali's Galachipa Upazila in winter and return to Charmontaz in the monsoon.

It is not only marriages that take place on boats in the Manta community, but their children are also born there. They grow up on boats and socialise with children of other boats. Manta women give birth without modern delivery care and cannot always get proper support if there is an emergency.

"Pregnancy- and childbirth-related complications sometimes arise, putting either the mother or the child or both at risk. We then try to arrange help, for example, by calling in a doctor or kabiraj (a traditional healer who practises Ayurveda)," explained Kalu.

He said they also resort to such informal medical help first when someone falls ill, instead of taking the person to a hospital. Such an arrangement means the survival of the sick often hangs in the balance if their condition is critical. "If Allah saves them, they live. Otherwise, they die. We cannot afford expensive healthcare in private hospitals," Kalu added.

Burying the dead is another big challenge. The Mantas, who follow Islam, do not have a dedicated graveyard, and no one wants to give them land for burial either. This sometimes forces them to bury the corpse on the riverbank or dispose of it in the river.

"We appealed several times to the local authorities for a dedicated graveyard, but have not got that yet. We buried some bodies in the old graveyard on the island, but they no longer want to allocate space for us. There is a private graveyard where they ask for Tk 20,000-30,000 for each body, which we cannot afford," Kalu lamented. Explaining this, Aiub said many Mantas over the years had been laid to rest in the old graveyard owned by the water development board, but it has almost run out of space.

The precarious livelihoods of the Mantas exacerbate their miseries. To make a living, they depend on the same rivers and water that uprooted their ancestors. Fishing is their primary source of livelihood, and women are skilled at it as well.

Rowing boats in rivers and canals, they catch fish with nets and fishing rods. They sell their catch at local markets and earn a small amount of money, which barely covers the cost of food and other stuff that the families need. A few Manta men also work on fishing trawlers that go to the deep sea from Charmontaz.

"It is not like the Mantas catch plenty of fish. We also depend on the Dadni system, which further strains us financially. Our women earn only Tk 5 by separating the heads from the bodies of a kilo of tiger shrimps," Kalu said, describing their intolerable levels of hardship. His wife sitting across him showed her swollen fingers and hands that resulted from regularly handling fish.

On the other side of destitution is the susceptibility to physical harm that the Mantas live with. They develop health issues, especially skin diseases, because of their prolonged exposure to the sun, water, and a range of weather conditions. Moreover, natural disasters like cyclones and floods pose great danger to them.

"We try to row fast to the shore if we get a disaster warning. If it is too late, we seek refuge in small canals or wherever we assume we will not be harmed," Kalu said.

However, this does not always protect them. Boats capsize and people, especially children, drown. It has also happened that they came out of their refuge in the river assuming the catastrophe had subsided or ended, only to be hit by it when the next phase of destruction began.

Identification is another major problem for the community. They do not have the national identity card (NID) because Manta births are not registered. Consequently, they do not qualify for support under the government's social safety net programmes.

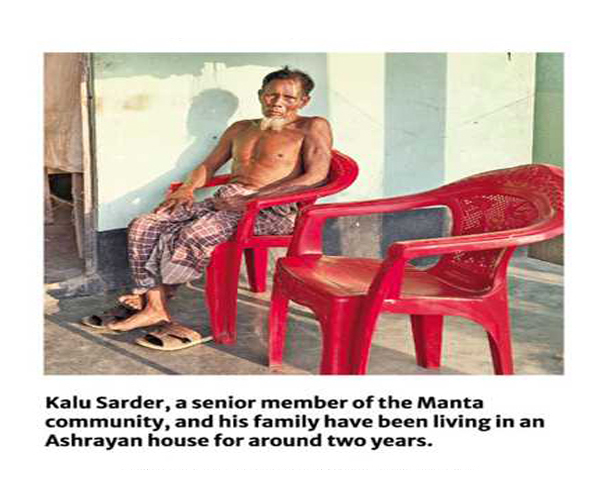

Kalu stressed the importance of arranging such support for Manta people's survival. He explained the absence of government assistance is a key reason why getting a house under the previous Awami League government's Ashrayan project has not brought about any qualitative change in his life. His survival still depends on fishing, and the scanty earnings have failed to mitigate his day-to-day suffering.

Fifty-nine Manta families in Charmontaz were rehabilitated under the Ashrayan project in two phases and given NIDs. The houses have been built in two blocks on the southwestern side of the island, not far from the launch terminal. From one of the blocks, Manta boats can be seen on the Tentulia River, which originates from the Meghna in Bhola.

Kalu and his family have been living in the Ashrayan house for around two years. He said the house gave him a roof over his head, but he is still struggling to keep his head above water. Several of his neighbours echoed him.

"Having lived on a boat and navigating the water for so many years, moving to land feels different. I now have comfort and peace. However, more support is needed to lift us out of poverty," Kalu added.

Education is a proven tool that can help people escape poverty, but it does not apply to Kalu. Like the older Manta generation, he is illiterate and cannot secure gainful employment. However, Manta children have also largely remained out of the mainstream education system.

The children learn fishing at a young age and grow up with the idea that they have to follow in their parents' footsteps for livelihoods. Barishal-based non-governmental organisation Jago Nari wanted to change this and set up a boat school in the Sluice Canal of Charmontaz in 2019 to provide pre-primary education. The school received an overwhelming response, with around 50 Manta children enrolling there every year.

There was a wind of change, and Manta parents also encouraged their children to go to school. However, in December 2023, the school discontinued its service as the project financed by the UK-based Muslim Charity ended. With tears rolling down their cheeks, the children waved goodbye when the vessel propelled away from the island.

A Jago Nari survey found that only 2 per cent of the Manta children in Charmontaz attend mainstream school. The Manta parents usually go fishing early in the morning and return in the afternoon. This is a key reason why they opt to take their children with them instead of sending them to school.

"We kept that in mind while setting up the school. We not only provided education but also ensured the children's safety so that their parents would not worry while fishing. Besides, we provided nutritious lunch to the students," Jago Nari Director of Communication Md Duke Ivn Amin told The Financial Express.

He said they had also built a permanent pre-primary school on Charmontaz. "It is a multipurpose building, which houses a cyclone shelter and a mosque. The community runs the school."

However, Aiub said the cash-strapped community is facing major difficulties in bearing the school's expenses. "Where will they get money? They already struggle to make ends meet. I am a teacher at the school and know the real situation."

He also taught at the boat school earlier and said the project's ending had put the children's education in limbo. "Now I am running the permanent school with my own money. I hired two employees and am paying them as much as I can from some informal businesses that I run. I do not charge the students tuition fees either."

Moreover, he noted that most of the boat school students transferred to local primary schools after the project's expiry have already dropped out. Distance is a major reason as the schools are at least three kilometres away, while Manta children also face difficulties in getting along with local students. Additionally, some children are ridiculed by their classmates.

"This happens when Manta children return to the classroom after fishing with their parents for one to two weeks. Their skin darkens because of prolonged exposure to the sun. Their hair turns reddish. Apart from being mocked for this, they also fail to catch up on studies," he elaborated.

Aiub has been working for the Manta community's development since 2013. He took some of them to the Patuakhali election office, including elderly women, to facilitate their NID issuance. Lobbying the local authorities, he managed support for 10 Mantas under the fisherman ID and maternity allowance for four women, but the payments no longer continue.

For his relentless efforts to improve the Mantas' condition, locals label him a member of the community. But he does not mind and keeps working with resolve. "We have to protect this community," he told The Financial Express.

The Mantas are finding it increasingly difficult to subsist on their bread and butter as commercial fishing and overfishing are diminishing fish stocks. On the other hand, they are becoming more and more vulnerable due to the adverse impacts of climate change, with Bangladesh ranking highly on the list of countries most prone to such devastations. Added to that is the cost of living crisis, which is aggravating their situation.

"I earned only Tk 50 today. How can I manage with that? We often starve," said Kalu, his voice full of despair. Several other Mantas also expressed such disappointment. This has far-reaching implications as some are going back to their boat life, sacrificing the comforts of home.

This is happening because the Mantas do not have any other source of income and do not feel comfortable doing anything other than fishing either, Aiub explained. "Women usually call the shots in the family, and this return is mainly led by them. As women are also adept at fishing, they are more interested in returning to the boats and earning money instead of sitting at home."

Like Kalu, Aiub also emphasised the need for government assistance for proper rehabilitation of the Mantas. He said they are not properly rehabilitated if they are still dependent on their boats to earn money and feed themselves. "Even those who have NIDs are not getting any government support. The support exists on paper only."

Rangabali Upazila Nirbahi Officer (UNO) Md Iqbal Hasan told The Financial Express he does not know why the Mantas are not receiving government assistance despite having NIDs.

"I assumed office around four months ago and have never been informed that they are not getting any support. Nobody from their community came to meet me. Besides, I do not know if they were excluded from the social safety net during the previous regime for any reason," he said.

He also said he would listen to their problems if a representative from the community comes to his office. He observed that the social security programmes are open to all and there is no way to exclude a particular community from the coverage.

Iqbal said he does not know whether the government has any plan to arrange alternative livelihoods for the Mantas. "I do not know if the previous administration took any step to this end either."

The Mantas have long endured the challenges of living on the water, and their resilience has brought them this far. But even resilience has its limits, and the community now wants a sustainable solution to their penury. "We need proper support - not just houses, but also livelihoods. We need healthcare, education, and the chance to build a better future," Kalu pleaded.

r2000.gp@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.