Published :

Updated :

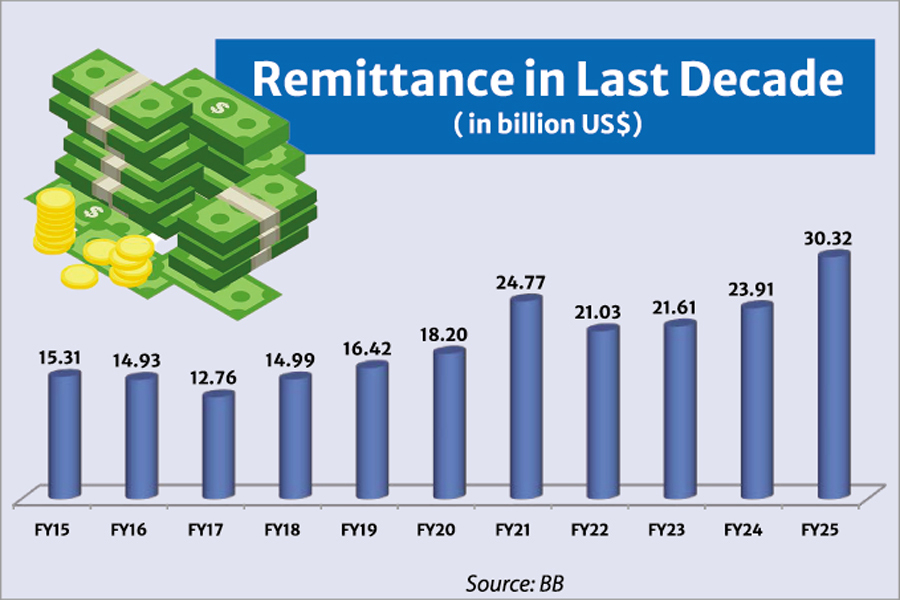

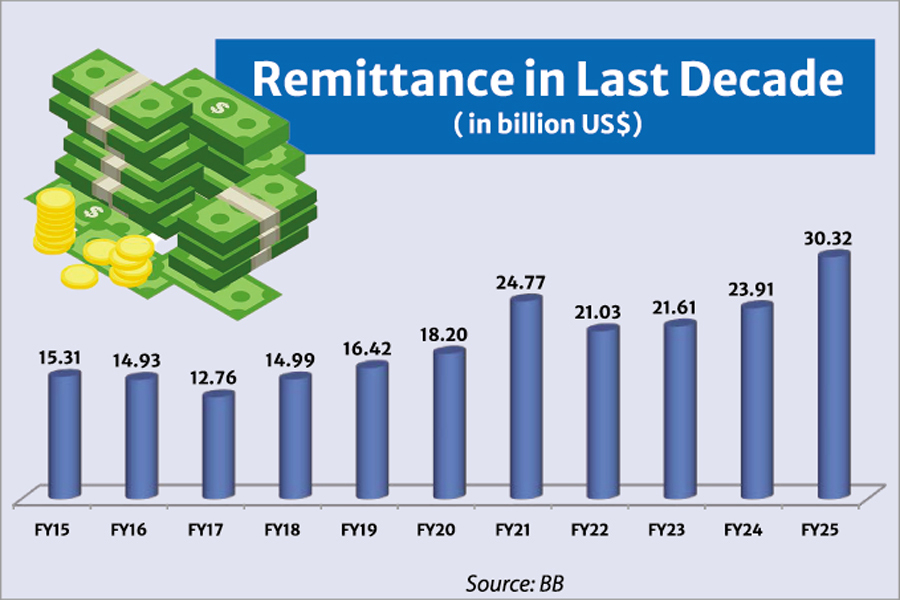

Remittance has long been a cornerstone of Bangladesh's economic stability and growth. The billions of dollars sent home by expatriates have served as lifelines for families, bolstered our foreign currency reserves, fueled rural economies, and underpinned banking liquidity. In the fiscal year 2023-24, remittance inflows reached an impressive USD 24 billion -- a figure that demonstrates the immense contribution of migrant workers to the national economy. However, a closer look reveals a looming threat: nearly 80 per cent of this remittance came from the Middle East -- a region now engulfed in deepening instability.

The Middle East, once seen as a dependable and generous host to Bangladeshi migrant workers, is today mired in relentless political and military turmoil. From the drawn-out war in Yemen and clashes in Lebanon to the ongoing crises in Syria and Iraq, the genocidal violence in Gaza, and the recent escalation in the Iran-Israel conflict -- the region is quickly becoming a tinderbox of global conflict. These developments are not isolated or distant; they strike at the very core of our economic security. With millions of Bangladeshis working in the Gulf states and beyond, any prolonged disruption in the region could result in mass job losses, forced returns, and a sharp decline in remittance inflows.

This is not a warning we can afford to ignore. It is imperative that Bangladesh begins exploring and developing alternative sources of remittance and foreign income without delay. The old adage "Don't put all your eggs in one basket" rings especially true for us now. We cannot continue to rely so heavily on one region for our economic lifeline -- especially a region so riddled with uncertainty.

The first and most immediate step is labour market diversification. Bangladesh must aggressively pursue new labor destinations across Southeast Asia, Eastern Europe, Latin America, and Africa. Countries such as Malaysia, Japan, South Korea, Romania, Belarus, Croatia, Poland, Brazil, and Chile are grappling with a shortage of skilled and semi-skilled workers. These are opportunities waiting to be tapped.

To access these markets, Bangladesh will need to deploy proactive diplomacy. This means forging bilateral labour agreements, offering mutual training recognition, ensuring worker protection, and building trust with host nations. It also requires private sector collaboration and streamlined government processes to facilitate quicker deployment of trained labor.

Many Bangladeshi workers currently employed abroad -- particularly in the Middle East -- are low-skilled or unskilled. But the demand in emerging labour markets is shifting toward skilled and semi-skilled categories. This mismatch presents both a challenge and an opportunity.

To bridge the gap, the government must prioritise skills development programmes tailored to international demand. Training in electrical work, plumbing, welding, nursing, caregiving, hotel and restaurant management, IT, digital marketing, and even niche areas like hairdressing can transform the earning potential of outbound workers. For example, hairdressing, often dismissed as a low-income trade, commands substantial income in European cities.

By investing in internationally accredited training programmes through technical schools, polytechnics, and public-private initiatives, Bangladesh can unlock a new generation of skilled migrants ready to meet global demand -- and send home greater remittances in the process.

Still, relying solely on exporting labour -- regardless of the market -- keeps Bangladesh vulnerable to external shocks. The more we depend on foreign economies, the more we expose ourselves to global volatility. Therefore, long-term resilience demands the creation of robust employment opportunities within our own borders.

Bangladesh has the potential to stimulate large-scale employment through the development of agriculture-based industries, SMEs, export-oriented manufacturing, freelancing, and entrepreneurship. These are not only avenues for reducing unemployment, but also for increasing domestic income and internal economic circulation.

Freelancing, in particular, has emerged as a major global trend, and Bangladesh is already on the map. After India, we are the second-largest pool of IT freelancers globally. Yet, in the absence of proper infrastructure, payment gateways, tax incentives, and policy support, our freelancers have not been able to translate their potential into substantial export earnings. By removing these bottlenecks, Bangladesh can turn freelancing and digital services into a billion-dollar export industry.

While remittances remain vital, export diversification must go hand in hand with labour market reforms. The ready-made garment (RMG) industry currently accounts for the bulk of our export earnings, but over-reliance on any one sector -- as with any one region -- is dangerous.

There are promising sectors just waiting for the right push: pharmaceuticals, agro-processing, leather, ceramics, frozen fish, light engineering, and handicrafts. With modern infrastructure, smart subsidies, and global market connectivity, these industries can generate substantial foreign exchange -- reducing our dependence on overseas labor altogether.

The IT sector again stands out as a game-changer. With a young, tech-savvy population and a growing digital ecosystem, Bangladesh can become a major hub for outsourcing, software development, and digital services. Countries like India, Vietnam, and the Philippines have already shown the path. All we need is the vision and commitment to follow it.

Should the Middle East crisis escalate, a large number of Bangladeshi migrants may be forced to return home. This influx, if not managed well, could overwhelm the labour market and increase social pressures. But if handled with foresight, it can become a turning point.

Returnee workers bring skills, discipline, and capital -- all of which can be channeled into domestic productivity and investment. The government must create an investment-friendly environment tailored to the needs of the returnees: access to land, bank loans, simplified regulatory procedures, and tax incentives. Such measures can encourage them to become entrepreneurs and employers. This not only ensures them an avenue for soft landing but also turns them into engines of economic growth.

Finally, awareness at the family and community level is essential. Many Bangladeshi households are entirely dependent on remittance, which makes them financially vulnerable. These families must be guided to explore alternative income sources, develop financial literacy, and think beyond remittance dependency.

This can be achieved through joint efforts by local government bodies, NGOs, and the media. Awareness campaigns, community-based entrepreneurship training, and microcredit access can prepare families to adapt and thrive -- even in a post-remittance scenario.

The political crises of the Middle East are not just geopolitical developments playing out on foreign soil -- they are directly connected to the fate of millions of Bangladeshis and the economic lifeline of our nation. We may not be able to stop wars in Yemen, Gaza, or Iran, but we can -- and must -- prepare for their economic fallout.

Now is the time for visionary leadership, not reactive firefighting. Now is the time for bold policies that prioritise human capital, innovation, and diversification. The choices we make today will determine whether we survive future crises or fall victim to them.

Bangladesh stands at a crossroads. It must move beyond the comfort of known markets and traditional remittance channels. A new era demands new thinking -- and exploring alternative sources of remittance is no longer an option; it is an urgent necessity. If we act wisely and decisively now, we can turn today's threats into tomorrow's opportunities. If not, we risk letting uncertainty dictate our destiny.

mirmostafiz@yahoo.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.