Published :

Updated :

In less than a week, the Trump administration's new tariffs will come into effect. Unless Bangladesh manages to strike a deal with the US before then, which it has been attempting to do for a while now, its exports will get slapped with a brutal 35 per cent duty starting August 1. From the look of things, Bangladesh is nowhere near securing a favourable settlement even after two and a half months of negotiations while competing countries such as Vietnam, India, Indonesia and Thailand have either reached or are very close to reaching a deal to get tariff cuts on their own exports.

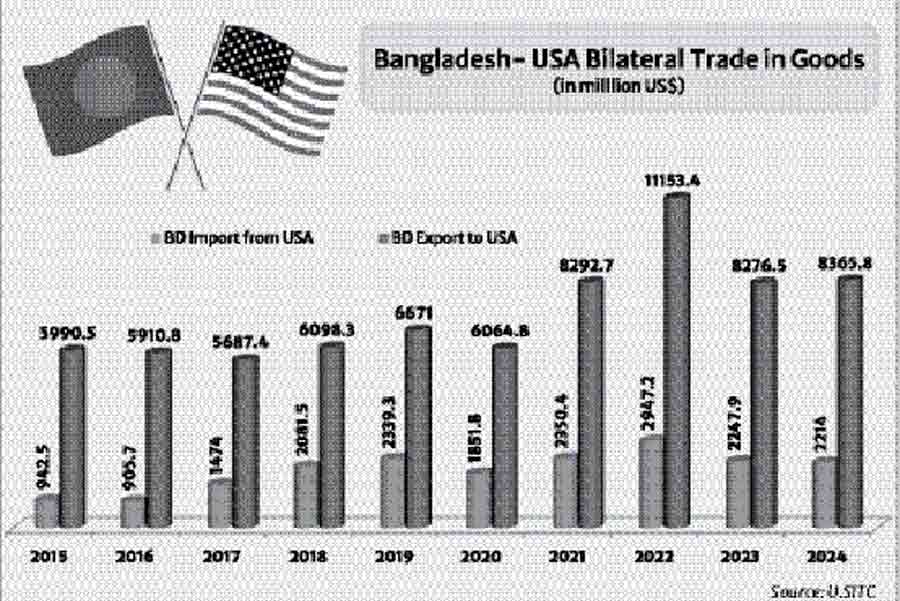

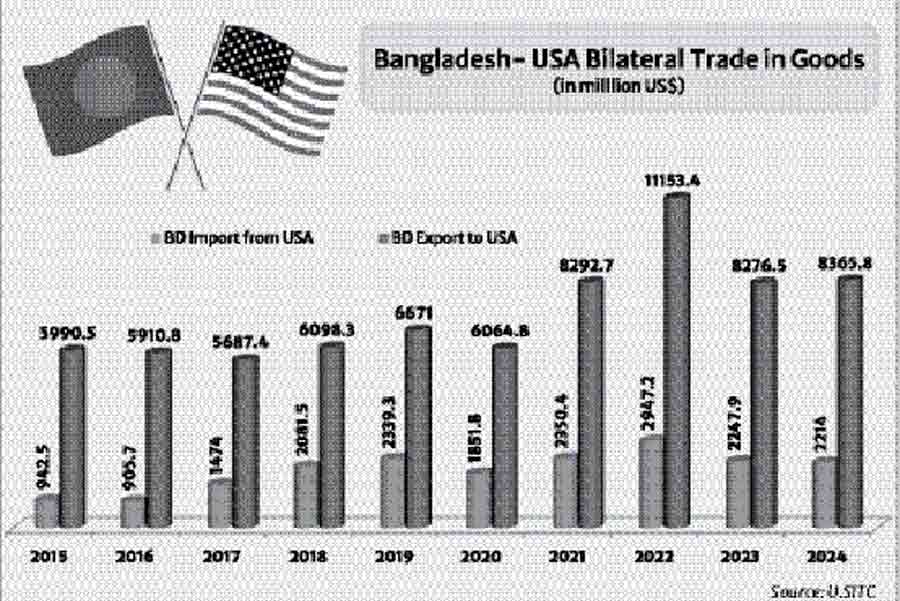

Given the situation, if those competitors receive lower tariffs and Bangladesh does not, it will be a major setback to the country's single largest export destination. Nearly $9 billion worth of annual exports, mostly garments, would take a direct hit because a tariff this high is almost guaranteed to reduce shipments. Buyers will definitely want to know how the additional 35 per cent tariff will be covered. Will they pass it on to consumers, transfer it to exporters or split it in some way? Until such questions are resolved, many orders are likely to be postponed. And unless some practical arrangement is made to decide who carries what share of the cost, buyers might choose to shift their orders to countries with lower tariffs in the end. That means the livelihoods of over a million garment workers who help produce RMG exports to the US would be at stake.

When these tariffs were first announced back in April with varying levels for various countries based on a trade imbalance calculation, most people assumed it was purely an economic move on the part of the US. It was only by mid-July, when a leaked US Trade Representative letter revealed certain conditions attached to the tariff discussions, that it became clear there was more to the story. Turns out, this wasn't just about money. There were strings attached. Bit by bit, it became clear that the US had brought national security, foreign policy and geopolitics into what was supposed to be a trade discussion. For instance, one condition demanded that Bangladesh comply with any US sanctions on other countries, potentially cutting off trade, commerce and investment with the likes of Russia and possibly China down the line. On top of that, there were other tough demands such as joining thirteen global treaties on intellectual property, adhering to strict rules of origin and so on.

This exposed two important realities. First, the US has obviously reverted to a Cold War mentality and is now employing tariffs and trade as tools to pull countries into its camp in a larger contest for global dominance. Bangladesh may be a tiny player in economic terms and a nonplayer in terms of military power, but even it has not been spared from the crossfire of global power politics. The US seems to believe it can weaken its rivals, especially China, through its tariff strategy. Given that the US has seemingly weaponised tariffs against Bangladesh, it is reasonable to assume it has done the same with other countries, and that those who were rewarded with favourable terms are the one that have quietly given in to its demands. Bangladesh, which has long upheld a foreign policy of friendship with all and malice toward none, now finds that very principle under threat. Being forced to take sides would not only break from this tradition but could also land Bangladesh right in the middle of someone else's conflict.

The second thing this whole episode reveals is how woefully unprepared Bangladesh has been in handling such a crisis. It is widely known that negotiations with the US are complicated and that countries seeking to influence American policy or retain trade benefits typically do so through registered lobbyists. That's how the game is played. Shockingly, Bangladesh entered this high-stakes negotiation without hiring any professional lobbyist. This decision, or oversight, has been nothing short of disastrous. While most countries rely on strategic lobbying, Bangladesh's attempt to manage the situation through bureaucrats and advisers alone only exposed its lack of preparation. Now there's talk of scrambling to hire lobbyists, but it comes too late and will likely not reverse the damage caused by months of inaction and miscalculation.

So where does that leave the country? Obviously, the US is asking for concessions that could economically tie Bangladesh's hands for years and force it to cut ties with China, something that would be extremely difficult if not impossible. Eventually, Bangladesh may have to offer some limited concessions that don't compromise its national interest, if not by the deadline, then soon after, if it hopes to secure an exemption or at least gain some breathing room on tariffs. Before making any counteroffer, however, the government needs to consult security, diplomatic and trade experts because these demands obviously touch on critical national priorities where their inputs would be invaluable.

Let us also not forget the power of personal diplomacy which can potentially make a difference under the circumstances. Countries that successfully secured trade deals with the US so far often had their heads of state speak directly with president Trump and that clearly played a role in sealing the agreements. For example, Vietnam's Communist Party general secretary To Lam and Indonesia's president Prabowo Subianto both held phone conversations with Trump. Bangladesh's chief adviser Prof Muhammad Yunus is not only a Nobel Laureate but also known for his charming personality and ability to influence negotiations. Should he engage in direct talks with President Trump, his personal appeal could well prove decisive in bringing a favourable outcome. That being said, no matter how desperate the situation gets, Bangladesh cannot afford to compromise its sovereignty or long-term principles just to get a temporary trade benefit. No deal can be worth that much.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.