Published :

Updated :

For decades, policymakers, labour rights activists and economists in Bangladesh have been drawing attention to the vast informal workforce involved with a large portion of the national economy. Despite its undeniable contribution, this sector remains excluded from official recognition, legal protection and social security coverage. As the country inches closer to its graduation from the Least Developed Country (LDC) category in 2026, the urgency to integrate this scattered and often invisible workforce into the formal system has become more pressing than ever.

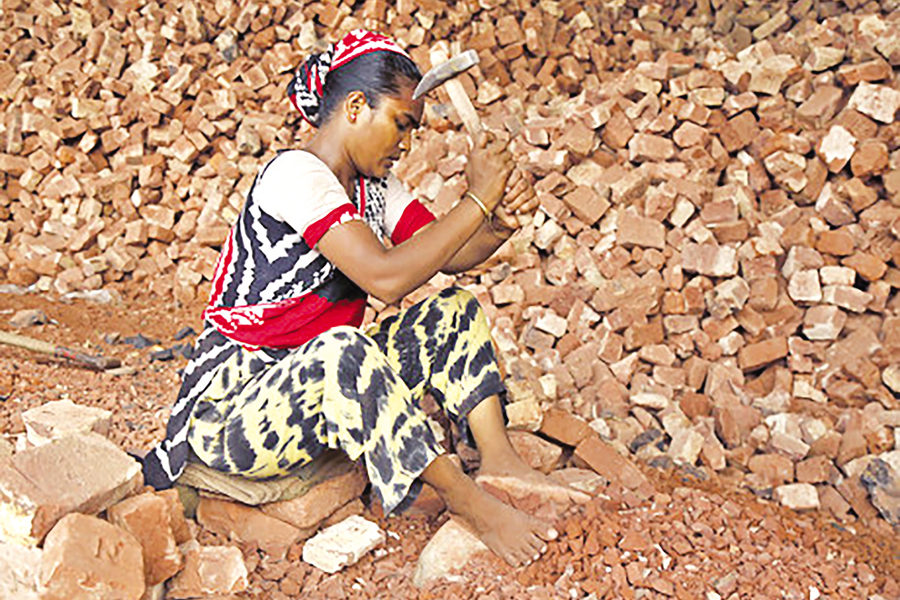

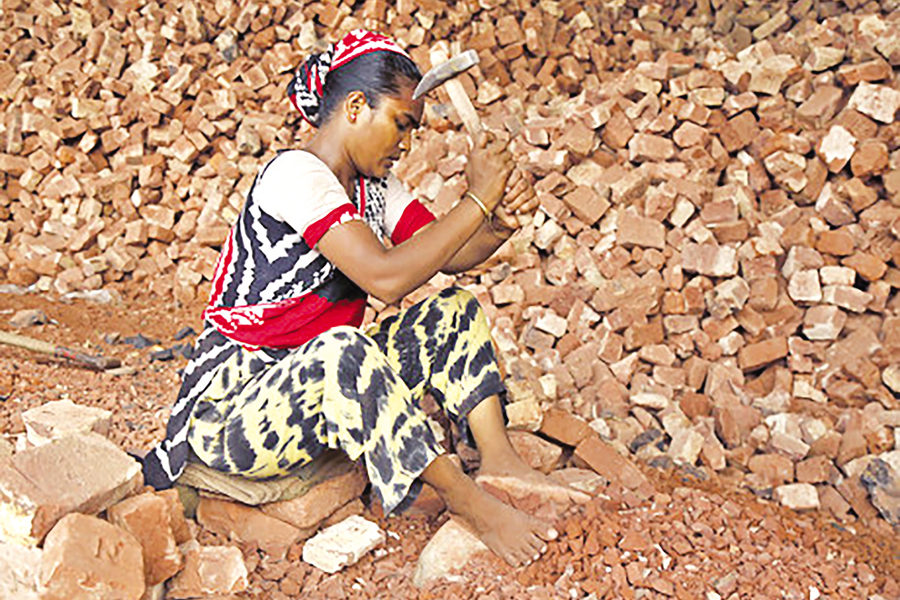

Informal employment refers to jobs that are not regulated, registered or protected under national labour laws. These positions typically lack standard employment guarantees such as paid leave, termination notice, pensions or health benefits. Instead, they rely on informal arrangements, personal relationships, or kinship ties rather than legally binding contracts. Workers in this sector have little or no access to unemployment insurance, workplace safety protections or social safety nets.

These jobs are most commonly found in small, unregistered businesses, micro-enterprises or households. A majority of these enterprises fall outside the tax net and government oversight. This means that their economic contribution remains largely invisible in policy design and implementation, despite being central to national productivity.

The recently published Labour Force Survey 2024 by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) highlights just how extensive informal work is. Out of a total labour force of 69.10 million, as many as 58.04 million - or 84 per cent - are employed informally. Breaking it down further, the survey shows that 95.96 per cent of female workers and 78.08 per cent of male workers are under this category. Geographically, 13.22 million informal workers are in urban centres, while 44.82 million remain concentrated in rural areas.

Sectoral distribution tells an even clearer story. Agriculture, long considered the backbone of the economy, has an overwhelming 97 per cent of its workforce in informal employment. The industrial sector has 89 per cent informal employment, while the service sector, often assumed to be more structured, still employs 67 per cent of its workers outside the formal framework.

These figures are not anomalies. In 2023, informal workers numbered 59.68 million - accounting for 84.07 per cent of the workforce - while in 2022, the share was 84.9 per cent. Prevalence of such high ratios shows that informality is not declining despite economic growth, export expansion and urbanisation. Rather, it remains a defining feature of Bangladesh's labour market.

The informal economy is not marginal, it is central. Various studies estimate that the sector contributes between 40 and 43 per cent of Bangladesh's GDP. A joint study by Karmojibi Nari and FES Bangladesh, which covered workers across all divisions, found that most informal jobs were concentrated in retail and sales, agriculture and livestock, food and beverage services, transport; and crafts. Nearly 69 per cent of these workers are aged between 25 and 44, underscoring that the most productive segment of the population remains deprived of protection and rights.

Without these jobs, millions of people would be unemployed or underemployed, creating severe social and economic instability. Yet, their contribution remains unacknowledged in government accounts, policy planning and wage structures.

Labour rights experts and worker leaders have therefore urged the government to formally recognise the informal workforce in the upcoming amendment of the Bangladesh Labour Act, 2006. Their demands include: a national wage board that considers the realities of informal employment, a digital national database to register all workers, linked with a unique worker identity card; and expansion of social protection schemes, including workplace accident and health insurance; and unemployment allowances.

Such measures, they argue, would not only uphold workers' rights but also allow the state to better manage and regulate labour relations in line with international commitments and the requirements of LDC graduation.

Leaving the informal workforce outside the scope of national labour legislation undermines both economic planning and social justice. Workers without contracts are vulnerable to exploitation, unfair dismissal and hazardous working conditions. Women in particular, who make up an overwhelming majority in the informal workforce, suffer disproportionately due to the absence of maternity benefits, workplace safety measures and wage parity.

At present, Bangladesh's Minimum Wage Board covers only 42 sectors, leaving the overwhelming majority of workers outside its scope. Unless deliberate efforts are made to expand coverage and include informal workers, the divide between formal and informal employment will continue to widen.

Experts stress that the proposed digital database should be dynamic, not static. It should be regularly updated and integrated with national identification systems so that government benefits - from healthcare support to accident insurance - can be directly delivered. Moreover, recognition of informal workers would allow the state to extend disaster-relief measures, microcredit facilities and skill development programmes more effectively.

The informal sector is not a temporary or peripheral aspect of the economy; it is its dominant reality. Yet, for too long, the millions who keep this sector alive have remained invisible in law, policy, and governance. Their lack of recognition not only denies them rights and protections but also diminishes their immense contribution to the nation's GDP and overall development. As Bangladesh prepares for the next stage of its economic journey, the inclusion of informal workers into the formal system is no longer optional, it is inevitable.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.