Published :

Updated :

Inflation kills the savers and awards the borrowers. At times, inflation is transitory, it does go away. But in today's world inflation stays for years if the government fails to control it. The tools are there to deal with inflation, but the government sometimes doesn't allow its central bank to use those tools for political reasons.

Interest rates should rise one-and-a-half times as much as inflation, suggested John B. Taylor, an economist. So if inflation rises from 2.0 per cent to 5.0 per cent, interest rates should rise by 4.5 percentage points. Would the Taylor rule work in today's economy? There are reasons for worry. Fiscal policy lives in the shadow of debt and political influence. We live in a world beset with unpredictable scenarios and the consumers' mindset has changed. Many attempts at monetary stabilisation have fallen apart because the fiscal or microeconomic reforms based on interest rates alone failed. Economic history is full of such episodes.

Turkey's central bank has recently announced it was slashing its key benchmark rate by 100 basis points from 15 per cent to 14 per cent. The move is taken despite soaring inflation with prices rising more than 21 per cent. After the decision, the value of the Turkish Lira has nose-dived, reaching 16 to a dollar from about 7 to the dollar earlier this year, making the Lira the worst-performing currency in major emerging markets. In 2008, one Turkish Lira could be bought in Bangladesh for TK 40, now it takes only TK 05.

Long queues outside basic food shops have become almost a commonplace of public life in Turkey. The prices of medicine, milk, toilet paper, and other necessities are soaring. The unemployment rate has shot up to more than 25 percent. Deeply negative deposit rates are incentivising people to opt for hard currencies like the dollar as well as gold, stocks, crypto-currencies, houses, or even cars as a protection method against inflation.

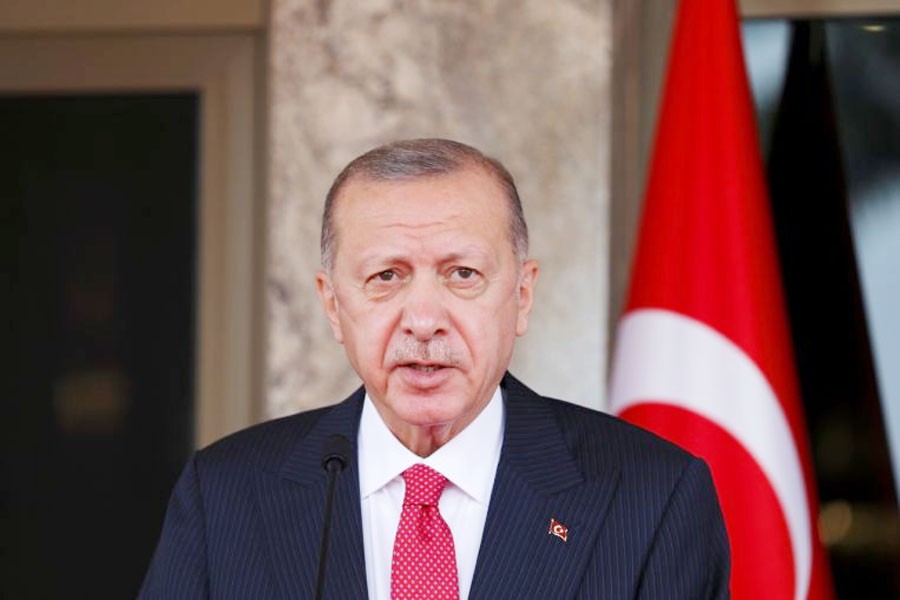

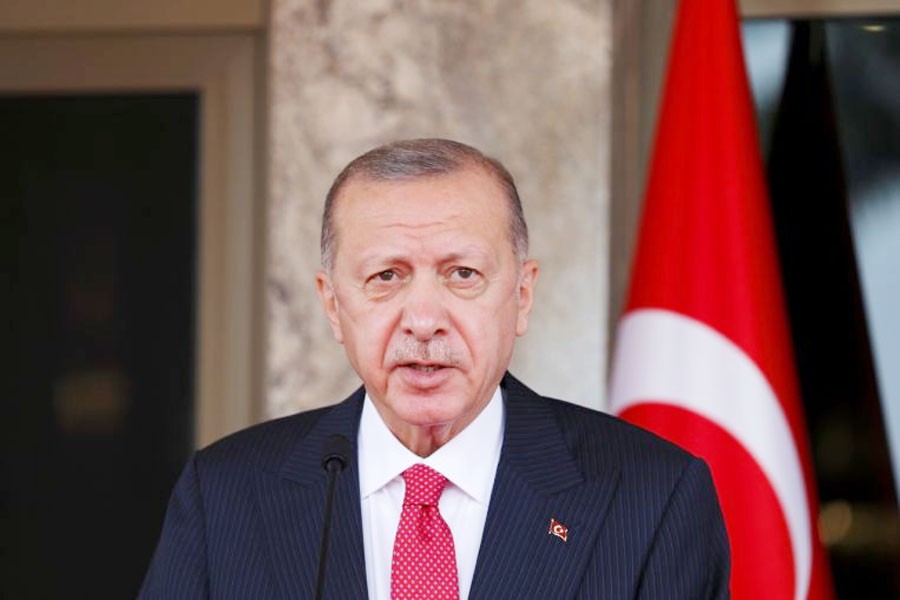

Skyrocketing prices are causing misery among the poor and impoverishing the middle class. Angry Turkish citizens are on the streets protesting the government policy of fiscal control through inflation. To quell public anger President Erdogan has announced on Saturday a 50 per cent minimum-wage hike to 4,253 Lira a month, or around $270, for more than 6.0 million people. But, the distribution of such largesses may rather exacerbate the inflationary pressure.

Turkey's economy is suffering from red-hot inflation. The economic train wreck has sped up with a ferocious intensity. The country may face hyperinflation if brakes are not applied to the supply of easy money.

Taylor's rule suggests that increasing interest rates is the best way to tackle inflation, but President Erdogan has been pushing for cuts as he thinks inflation is the best way to stimulate the economy.

On the other hand, the Bank of England has just raised interest rates from 0.1 per cent to 0.25 per cent in response to calls to tackle surging price rises. Inflation in England is now running at 5.1 per cent, the highest in a decade.

While England has raised interest rates Turkey has slashed the rates to fight their common problem of inflation. The impact of the slight rise of interest in England is yet to be seen. But Turkey's decision of cutting interest rates by 1 percent has seriously impacted its economy.

Why is President Erdogan so wedded to this alternative path to cut interest rates time and time again when inflation is high? It's an enigma to the economists.

Mr. Erdogan has replaced a series of Central Bank chiefs and finance ministers in recent years, confident that he knows the economy better than any of them.

President Erdogan, a graduate from Marmara University's Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, doesn't buy Taylor's idea. Interest rate, Mr. Erdogan reportedly thinks, is the mother and father of all evil. He doesn't want to see rates move higher. He believes in a low rate that propels growth. This is true theoretically provided concomitant factors complement the move. But Turkey is heavily dependent on imports like automobile parts and medicine, as well as fuel and fertilizer, and other raw materials. When the lira depreciates, those products cost more to buy.

Central banks typically target an annual rate of inflation usually not more than 2.0 per cent, believing that a slowly increasing price level is good that keeps businesses profitable and prevents consumers from becoming stingy on spending. Prescribing inflation, to a measured dose, enlivens a stagnant economy, preventing the Paradox of Thrift. Small inflation attracts investors and tourists. But, over-prescribing of inflation, like over-prescribing of antibiotics, yields disaster that may trigger massive unemployment and even stagflation.

With an election coming up in 18 months, Mr. Erdogan seems doggedly staunch that his strategy based on low-interest rates will reinvigorate his country's economy despite the current crises as he is still inspired by his aggressive pro-growth strategies in the past that were successful.

Mr. Erdogan is popular in his country, especially among the poor. He is also popular with people from poor countries of the world. He is among the few leaders in the western world who immediately respond to any humanitarian crises. He declared on Saturday his country is sending 15 million Covid-19 vaccine doses to Africa.

Turkey once witnessed an economic miracle during the first decade of Mr. Erdogan's rule. Huge infrastructure projects were implemented, foreign investors enthusiastically poured their money into Turkish businesses, consumers and businesses were encouraged to avail of loans at cheap rates. Poverty was sliced in half, and millions of Turkish people rose to the rank of the middle class. Phenomenal growth took off.

But now the time has changed. With new covid variants emerging in different shapes and colors people are not eager to spend money and the overall economic outlook of the world does not look promising. Tweaking interest rates, upward or downward, on the part of central banks would do little to stop prices from going up or down since costs are being influenced by global factors largely outside a central bank's control. Circumspection is required in the use of fiscal tools to face the new challenges.

The Head of a government may give broad guidelines on technical issues that are outside his purview. He may ask his finance minister to take measures to improve the economy. But he should not be in the driver's seat on roads that determine the economic fate of his countrymen. The roads are pretty curvy in the domain of economics. Steering around those curves can be tricky and potentially cause you to lose control of your vehicle unless you are a professionally trained driver.

Mr. Erdogan's inexorable push to expand at the expense of people's buying power may turn out to be too risky a gamble to win at. If he wins defying the theories of Economics, the world will witness a second Turkish miracle thanks to Erdogan's own economic philosophy that observers have already dubbed 'Erdoganomics'. If he doesn't, the future of Turkey under his captaincy, and his prospect to be reelected, seems uncertain.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.