Published :

Updated :

Is our debt sustainability out of danger? Widely used and pronounced International Monetary Fund or IMF-dictated ratio of debt to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is considered to be the single major determinant of debt carrying capacity of a country. But this ratio is unrelated, unrepresentative, and ineffective in view of debtor's real capacity to repay debt. Besides GDP, export, remittance, and gross revenue, too, cannot be appropriate denominators to compute debt ratios to indicate debt carrying or repaying capacity. We are really worried over what is actually occurring beyond our knowledge and consciousness. The real scenario needs to be investigated into to measure the distance of impending distress as we want to make our journey of development free of major hurdles. We are also not ready to pay the exorbitant cost of mismanagement.

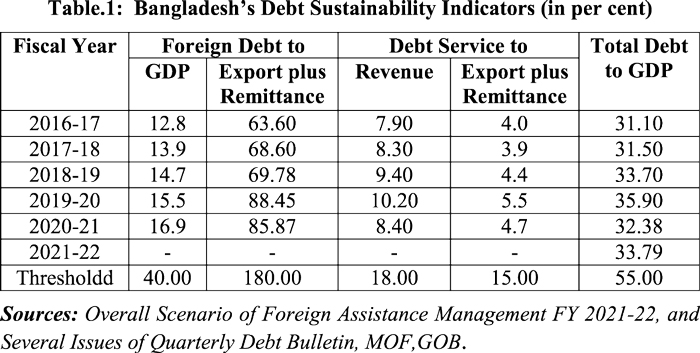

As per IMF report, Bangladesh's total debt to GDP was 39 per cent while External debt to GDP was 17 per cent in FY22.The external debt threshold is 40 per cent while that of total debt to GDP is 55 per cent. Debt service threshold to export is 15 per cent and that to revenue is 18 per cent. Judged against the aforesaid benchmarks, we are, as described by IMF, safe to carry the existing level of debt. As the denominators used in the debt ratios are not selected appropriately, the hidden debt scenario needs to be unearthed to know where we are heading towards.

Table-1 provides some indicators on our debt sustainability. As already mentioned, they are not relevant and properly related because incomes on export and remittance as well as GDP are not owned by the government. Revenue is totally the government's own. Despite that, the government is first obligated to spend for revenue or non-development expenditure from revenue, and then can use the residue (if any, i.e. revenue surplus) for a partial payment of debt service or development expenditure. The ratios apparently give us an optimistic picture since they have not surpassed the IMF thresholds.

Table-2 shows contradictory relationships against the data presented in Table-1, and simultaneously unveils some indicative facts in spite of improper denominator (i.e. Revenue and Grants in lieu of surplus from revenue only). Debt service to revenue ratios of Table-1 is quite inconsistent with those of Table-2 particularly in 2020, 2021 and 2022. On the other hand, debt service to revenue and grants ratios of Table 2 provides the truth that the lion's share of revenue and grants is exhausted in debt service payments. With exclusion of grants, the status would have been worse. Another truth revealed in Table 2 is that revenue collection is less than 10 per cent or around it even up to a period (both historical and projected) of 10 years later from now. Debtor-creditor data incompatibility also complicates the scenario.

Table-3 presents highly significant information on our real capacity to meet and finance debt service payments as well as development expenditure. It is alarmingly observed that we are almost unable to repay debt and spend for development from equity fund, i.e., own income. Debt is being repaid by way of further debt financing. We have been obsessed with debt to GDP ratio which has remained below the threshold set by the IMF. As compared to GDP growth and volume, revenue collection is very inadequate while revenue is the fundamental and the single biggest source of a government's equity fund. It is the revenue earning capacity that determines a government's debt carrying as well as repaying capacity. Table 3 already exhibits the government's very poor capacity measured by the size of revenue surplus which is just 2-3 percent of GDP.

A country's public debt is considered sustainable if the government is able to meet all its current and future payment obligations without exceptional financial assistance or going into default (Finance & Development, September 2020). The journal issue further adds that a country's debt-carrying capacity depends on several factors-- among them, the quality of institutions and debt management capacity, policies, and macroeconomic fundamentals. Preliminary observations over a period of 5 years (Table 3) hint that we might have already quite unnoticeably and inconceivably sunk into debt distress owing to our inert, inept, and blind reliance on external methodology regarding benchmarks. Our debt sustainability may be described to be at stake according to the criteria expressed in Finance & Development. A comprehensive review of debt trends and actual equity-based repayment capacity on our own criteria should be carried out on an emergency basis.

Revamping debt management has become very crucial. Actually, we lack a truly representative and effective indicator devised on our own prudence. Here lies the inherent shortcoming of our debt management. Fundamental perspective differs between a debtor and a creditor. Debtor's insightful and interest-conscious bargaining power can optimise the degree of differences. As compared to the past, debt statistics and reporting have progressed a lot, but debt management is yet to be equipped with a strong analytical framework. Simple accounting and analysis (instead of highly sophisticated one) as inserted in Table 3 can easily provide an early warning of any crisis or distress. The choice of related and appropriately representative denominators for relevant debt ratios is an urgent task well before we confront a unmanageable disastrous situation.

Haradhan Sarker, PhD, ex-Financial Analyst, Sonali Bank & Professor of Management (Rtd.).

sarkerh1958@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.