Published :

Updated :

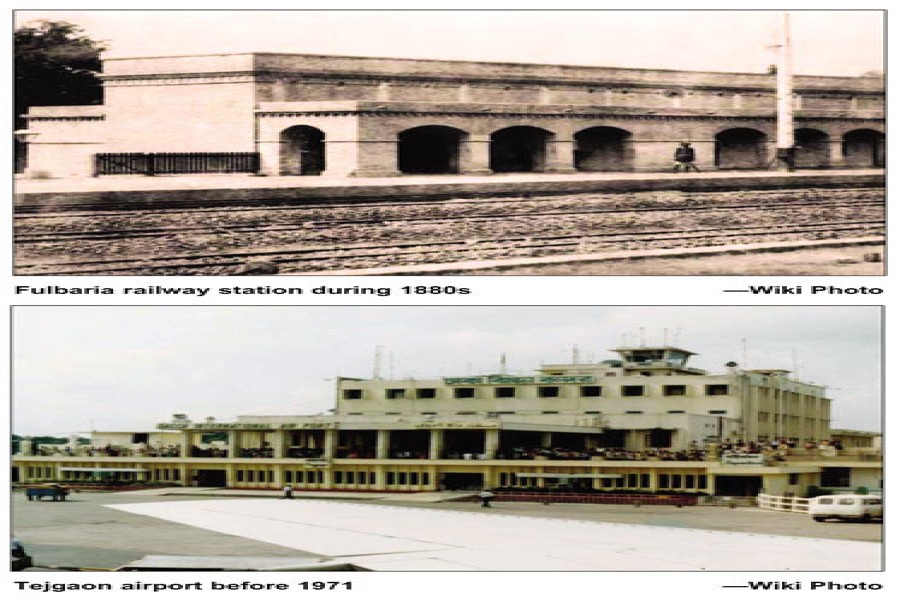

After the Dhaka Airport in Tejgaon had been shifted to its massive building at Uttara under its new definition as an international airport, speculations were rife about the old airport. Some said the old building along with its runway, tarmac, watchtower etc would be preserved as a historic relic. After all, lots of World War-II memories remain associated with it. The authorities at one point of time said the whole abandoned airport complex would be turned into a public recreation centre, with vast areas kept for strolling in the afternoon. A lot of others were in favour of demolishing the complex. They advocated the construction of high-rise buildings there for different kinds of use.

As the area belonged to the Bangladesh Air Force, the final say depended on it. The BAF decided to preserve the area as a specialised airport for its own aircraft and helicopters.

Apart from honouring the historical reason due to its being the first complete airport in East Bengal, it had other factors behind the rationale for its right to remain in place. Many events of the first half of the 1970s are inextricably linked to Tejgaon Airport. It is this airport through which Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman entered the independent country from Pakistani imprisonment for 9 long months beginning March 26. People by the hundreds gathered at the airport to welcome him as the Bengalees' supreme leader. Earlier, on a number of occasions the leader went to the then West Pakistan on negotiating missions through this airport. The nation's closest ally during the 1971 Liberation War --- Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi's official aircraft touched down on this airport in 1972. Many other historical events that occurred in the newly independent country had centred round this airport.

Tejgaon Airport stands still today in its own unsurpassable glory. Its outer part has undergone little changes. The only difference is the once-bustling airport is now eerily silent and deserted. Four decades ago the whole area remained throbbing with the occasional takeoff and landing of early-model Boeings (Biman and PIA), domestically flying Fokker F-27 Friendship aircraft (Biman), Dhaka-Karachi Lockheed Super Constellations (PIA), and the now-abandoned, old-model small airbuses (PIA). Apart from the aircrafts' roars and muffled buzz, the whole concourse hall would remain filled with assorted types of noise, mainly human voice. The Tejgaon Airport remains standing, thanks to the intervention of the Bangladesh Air Force.

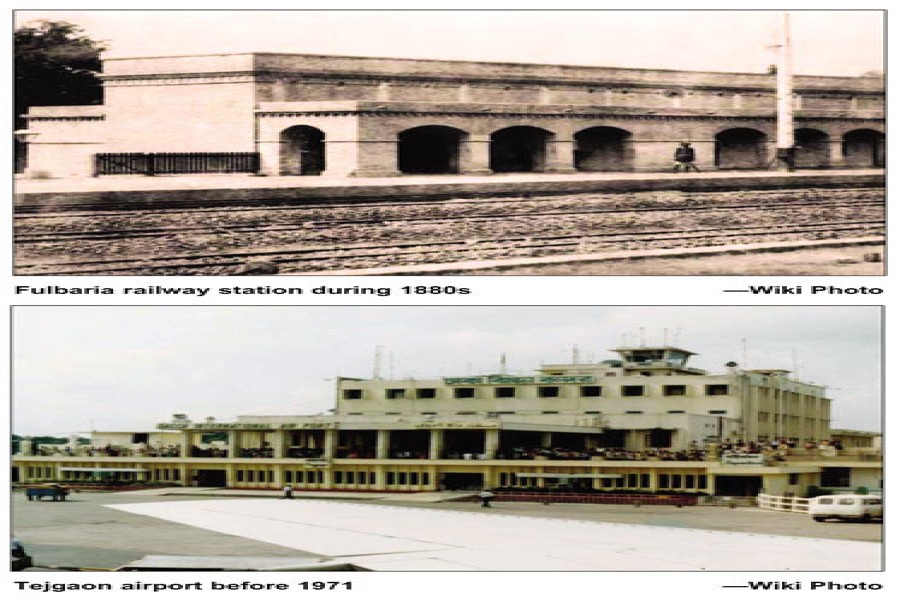

Unfortunately, there are no traces of the red-brick Fulbaria Railway Station once standing on the bordering line between Old and New Dhaka in the Nawabpur area. The 19th century station building could have been preserved as a valuable historic relic. It would not have created hindrances to the commercial developments of the area. The inoperative station building remained standing for almost a decade before it was torn down. A large bus depot and a hawkers market grew up there overnight. There were no signs which spoke that a busy railway station once stood there. To many urban planners and even modernist architects, the demolition of the Fulbaria Station amounted to a structural atrocity. Leaving aside all its important aspects, the station building with a steam engine and two compartments on a strip of railway tracks would have added to the architectural beauty of the old Dhaka landscape. Few in the authorities bothered to think in that line and show the eagerness to preserve Dhaka's heritage.

Many of this historic city's architectural and heritage-related treasures have been flattened upon the so-called demand of time. Another glaring example is the coal-run power generation centre at Hatirpool near Elephant Road. Once upon a time, rickshaw passengers in other parts of the city would hire the 2-wheelers for taking them to 'Power House', meaning today's Hatirpool. The very mention of Hatirpool as a destination will puzzle today's transport operators moving on hire in the city. The authorities could have, at least, kept the two tall mega chimneys in place. They used to spew out smoke from the burnt coal. Those were visible from a long distance. The iconic Power House is long gone. So are the remnants of Hatirpool (the Elephants' Bridge), which was used as a safe passage to help elephants from western Dhaka go over the rail tracks below. The trains used to pass through a tunnel built under the 'elephants' bridge'. Both are gone. They could have been preserved as two major relics from Dhaka's past. Fortunately, the Mughal-era Dhaka Gate in the university area still stands in a dilapidated state.

Many century-old hotels, railway bungalows have been razed to the ground in this city. The reason that relates to hotels: their limited occupancy capacity and insufficient modern recreational outlets and other amenities. The name which comes first in this category is that of Green Hotel in greater Paribagh. The one-storey hotel was once a popular hangout of Dhaka's emerging merchants and 'aristrocatic' intellectuals. Besides, some of its special cuisines had made it a reputed food and snacks joint. After the hotel was shut down, the fame of a hotel being a popular local and overseas food centre went to Purbani Hotel in Motijheel. The hotel still stands with its distinctive glory. It's amazing that the historic hotel keeps drawing its clients, especially in the days of ubiquitously growing business of 'starred' hotels. Purbani became popular for its lunch-boxes and the cheaper but luxury residential and room service facilities. The hotel quite competently hosted a number of critical political meetings in the 1980s.

Despite being a provincial capital, Dhaka was once famous for its railway bungalows in the greater Fulbaria and Abdul Gani Road. After a series of experiments with the promenade built along the Buckland Bund in Sadarghat on the bank of the Buriganga, the pleasant riverside venue eventually lost its charm. In course of time, it simply disappeared in the jungle of dingy shops and trading activities and illegal structures. The fabulously beautiful pastime site was constructed by Charles Thomas Buckland in 1864. British high officials and their wives would be seen sauntering along the riverside Bund. Many would be seen seated on their horse-drawn phaetons along with their children. Thomas Buckland was the commissioner of Dhaka during that period.

When one becomes nostalgic about the greater Sadarghat, one doesn't fail to hark back to the Northbrook Hall, the Ruplal House and the now-vanished office of the Dhaka Municipality. The former two somehow manage to stand erect. The location of the last one creates debate among today's younger generations. Being less important than the other Bengal city --- Kolkata, the British India's capital for 139 years, Dhaka didn't see any infrastructural growth like the former. Notwithstanding this fact, Dhaka had its own distinctive glory and fame. The image had its origin in Dhaka's reputation for being the birthplace of muslin. The later centuries earned a lot of splendour and magnificence for this historic city. Narrow parochialism within Bengal political circles has deprived Dhaka of many rewards of structural development owed to it. It's a long story.

Lamenting the slow death of three buoyant rivers which used to flow across Dhaka now sounds a little hackneyed. We have shed a lot of tears over the decades; the rivers show no sign of returning with their past awe-inspiring beauty. Same is the case with the proverbial canals and 'dighis' (large ponds) of the city. Against the depressing backdrop of structural extinctions in Dhaka, the speculations of replacing the historic TSC building on the DU campus with a multi-storey, modernistic edifice fill many with an unexplainable grief. It should prompt others to keep in mind the imperative of putting in the last-ditch efforts to retain as best as possible the original design in the rebuilt structures --- like the Kamalapur Railway Station.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.