Published :

Updated :

The July 2024 Mass Movement brought to the fore the long-standing unaddressed development challenges of rising inequalities in wealth, income, and economic opportunities. A particularly concerning reflection of these inequalities is the growing incidence of youth unemployment. Addressing this matter with thoughtfulness and diligence will be a pressing policy issue for the upcoming elected government. What are the key elements of this youth employment challenge?

First and the most important issue is the low quality of the entire labor force. While a growing labor force provides Bangladesh with a major source of faster gross domestic product (GDP) growth, the quality of the labour force in terms of education and training is weak that prevents the ability to benefit from this demographic dividend to its true potential.

Second, a related supply side constraint is the continued low female labor force participation rate, estimated at a mere 38 per cent in 2024.

Third, on the demand side, GDP growth has plunged in recent years falling to a low of 4 per cent in FY2025. Even when GDP growth was in the 7-8 per cent range, overall job creation, especially in manufacturing, slowed considerably. A particularly disturbing factor is the negative employment growth in manufacturing during 2013-2024. The falling GDP growth path is a double blow for job creation.

Fourth, some 84 per cent of total employment is defined as informal employment, where the employment conditions are often inconsistent with decent jobs involving written contracts, attractive remuneration, internationally acceptable work hours, job security, and safe work environment.

Fifth, evolving global technology supporting labor saving and capital-intensive modes of production combined with the Artificial Intelligence (AI) revolution is rapidly changing the global and local employment landscape with growing demand for tech-savvy and highly skilled labor force and diminishing work opportunities for low-skill, non-technical work force. This has led to a rapidly widening skills gap in Bangladesh and is presenting a major challenge to the employment relevance of the Bangladesh education system.

A fifth and fundamentally important concern is the growing incidence of unemployed youth, defined as workforce falling in the age group 15-29. As of 2024, some 35 per cent of the labour force fell under the category of the youth labor force with an unemployment rate of 8 per cent. Additionally, some 20 per cent of the youth population is not in employment, education, or training (NEET). Combining the unemployed youth and the NEET youth, a staggering 10.6 million youth are either unemployed or belong to the NEET category, suggesting a colossal economic loss as well as a huge social problem that could easily destabilize the socio-political environment.

Finally, the youth employment profile suggests a strong move away from agriculture into industrial sector, services, and international migration. Yet, the average earnings of the youth labor force in each activity are substantially lower than the adult workforce (30-64 years). Also, an overwhelming proportion of the youth work in informal employment.

Factors that Explain the Current Youth Employment Challenge: Low quality, low earnings youth employment, a high rate of youth unemployment and a large percent of youth NEET all raise serious concerns about the ineffective use of the demographic dividend. Several constraints working on the demand and supply sides of the labor market explain this.

Demand side constraints. At the national level total job creation has slowed down considerably despite rapid manufacturing sector -led growth. The most important reason for this is the enterprise consolidation and automation in the Ready-made Garments (RMG) Sector. The RMG sector created some four million jobs, mostly for young women, between 1990 and 2012. Since 2013, the consolidation of the RMG sector owing to automation, compliance with safety and other buyer-induced regulations, and scale economies has resulted in a noticeable reduction in the number of RMG enterprises, mostly small-scale in nature and intensive in low-skill female-oriented employment. This has caused a virtual stagnation in RMG total employment at around 4.0 million despite rapid growth in RMG production and exports.

Second, the RMG success that created an export-oriented labour-intensive manufacturing sector has not been repeated elsewhere in manufacturing for a range of reasons including a heavy anti-export bias of the trade policy. This has constrained the growth of manufacturing sector jobs.

Third, inefficient import substitution supported by continued large trade protection has failed to take-off in a big way in terms of dynamising the domestic market-based production structure. The employment effect of this import-substituting manufacturing has been modest.

Fourth, the micro and small enterprises (MSEs) are the backbone for non-farm job creation in Bangladesh. According to the 2013 Economic Census, some 99 per cent of all non-farm enterprises fall in the MSE categories and they provided employment to 20.3 million people in 2013. This makes them the largest source of employment outside agriculture. This sector is mostly informal in nature and lacks dynamism owing to a variety of constraints including financing, technology, and institutional support. Non-farm job creation economy wide will benefit most by strengthening this sector.

Supply side issues: schooling gaps and quality of education and training. Fifth, notwithstanding progress with education enrolments, there is still a substantial enrolment gap at the secondary and higher secondary school level combined with large incidence of dropouts at both levels. When the numbers of youth not enrolled in school and dropouts are added, the schooling dimension of the youth challenge for the age group 15-19 becomes obvious. Many of these out of schoolchildren are a part of the NEET group.

Sixth, the access to training is extremely limited. According to LFS 2024, 99.5 per cent of the workforce did not have any access to training.

Seventh, an even bigger challenge is the quality of education and training. The quality issue is pervasive and runs through the full course of the education system starting from primary to tertiary (both general and technical). The quality concerns include low learning levels, inadequate acquisition of non-cognitive skills, inequitable learning among students, a high degree of variation between schools, low teacher motivation, low time on task, weak examinations and teacher development systems, limited incentives for performance, little disincentives for poor performance, and low levels of financial accountability.

Eighth, female youths face additional challenges based on gender discrimination, mainly related to social norms. A major social bias is the incidence of early marriage despite legal restrictions. Out of home safety risks and lack of basic privileges like access to toilets create additional work barriers for the female youth

Finally, a major consequence of this weak education and training system of Bangladesh is a high rate of youth unemployment despite completing higher secondary and tertiary level education. Basically, the school graduating youth are not fully equipped to face the needs of the job market, especially in this rapidly changing global environment of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. While employers are demanding higher-skilled professionals for technical and managerial positions to support the growing industry and service sectors, tertiary education institutes are struggling to produce employable graduates for the job market. Unemployment rates are consistently high among tertiary graduates, causing prolonged and frustrating joblessness for many.

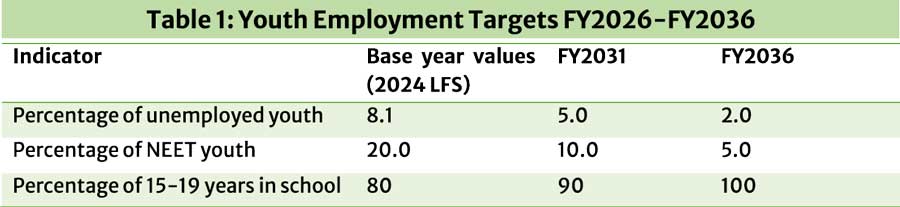

An Approach to Bangladesh Youth Employment Policy Framework: An urgent policy priority for the new government would be to develop a comprehensive national policy framework for youth employment (NPFYE), underpinned by quantitative youth employment targets to measure progress. An indicative youth employment targets for the next ten years are shown below.

The NPFYE could be organised under three themes: the labor market demand side policy interventions; the labor market supply side interventions; and interventions to promote self-employment.

Demand Side Measures: Eliminating the anti-export bias of trade policy. Learning from the success of the RMG sector, Bangladesh should promote a diversified labor-intensive export base by eliminating the anti-export bias of trade policy through systematically reducing its tariff and para tariff rates on consumer goods over the next 4-5 years. In addition, the government should avoid a real appreciation of the exchange rate and address the multitude of behind-the-border reforms that constrain the growth of both export and domestic manufacturing sector.

Dynamizing the micro and small enterprises (MSEs). A substantial part of the youth workforce is engaged in this sector. The policy challenge here is to dynamize this sector with a view to strengthening its capital and technology base and raising average labor productivity. Several steps can be taken to boost this sector.

The highest policy priority is to enhance the access of MSEs to institutional finance. The main reforms include: adapting regulations to serve the needs of the informal MSEs; simplify business procedures for MSEs; improve the efficiency of credit market information; enact law to set up secured transaction register; establish a central coordinating agency to promote MSEs; develop capacities of the banks and non-bank financial institutions to better service the financing needs of MSEs; establish small claims court; introduce a credit guarantee scheme; promote digital financial services; promote fintech options; and promote crowd funding, angel funding and venture capital for MSEs.

A second policy priority is to mainstream this sector in national strategies and macroeconomic policy making relating to fiscal, monetary, trade and industrial policies. To enable this, a solid diagnostic study of MSEs based on a comprehensive survey should be conducted urgently. This survey should provide a much-needed baseline database for MSEs

Third, international experience shows that a coordinated approach to policy making with annual monitoring of progress is essential for the growth of MSEs. For example, in Japan the Ministry of Industry and Trade (MITI) provide this coordination. Bangladesh needs to establish a similar monitoring and coordination mechanism. The MSE database needs to be regularly updated to enable measurement of progress.

Supply Side Measures: The biggest policy challenge on the supply side of the labor market is to increase the quality and relevance of education and training to the job market.

Ensure quality universal primary, secondary and higher secondary education (age 6-18). As per SDG target 4.1, Bangladesh needs to ensure 12 years of compulsory education for all children by 2030. This will mean that children 15-18 are not in the work force and instead are a part of the school system, which will reduce the incidence of youth unemployment and youth NEET.

The issues facing the education sector on both the quality and quantity front are well known; the main challenge is implementation. Among the major policy and institutional reforms needed to achieve SDG goal 4.1 are: sharply increase budget allocation for education and training from 1.8 per cent of GDP to 3.0 per cent of GDP by FY2030 and 4.5 per cent of GDP by FY2035; decentralize education system delivery to local government institutions (LGIs); sharply upgrade teacher quality by adopting a long-term teacher professional development program learning from the experiences of East Asian and OECD countries; strengthen teaching of science, mathematics and ICT; and upgrade school facilities including buildings, furniture, playground, labs and ICT equipment.

Strengthening access to vocational tertiary education. The SDG target 4.3 calls for ensuring equal access for all people to affordable and quality technical, vocational and tertiary education, including university by 2030. The recent rapid growth in the supply of private tertiary education in Bangladesh is a strength. The government has also made progress in increasing the supply of publicly provided tertiary and vocational education at the district level, which is partly aimed at increasing the access of the female youth to tertiary and vocational education. Yet, there is a substantive unfinished agenda. The major policies where further efforts are needed include strengthening of public-private partnership in the supply of vocational and tertiary education, public funding for scholarships focussed on the female, public funding for capital grants to upgrade education facilities, and better supervision and monitoring of accreditation policies. On the institutional front, the main reform needed is to strengthen the University Grants Commission by increasing its autonomy, instituting high-quality management, and ensuring transparency of decision-making and full accountability.

Integrating ICT education in the education system. Progress in integrating ICT in education has been constrained by low public spending on education that severely limits ICT education facilities at the school level and the availability of trained teachers. These need to be resolved speedily.

Upgrading vocational and technical skills of potential work force. The relevant SDG target relates to Goal 4.4, which states that by 2030 there will be a substantial increase in the number of youth and adults who have relevant skills, including technical and vocational skills, for employment, decent jobs and entrepreneurship. The strengthening of vocational and technical skills of the potential work force is a critical requirement to address the demand -supply gap for skills in the labor market. Higher public spending for education must prioritize learning of maths, science, ICT, and vocational training.

Strengthen the skill base of the existing youth labour force. There are two types of unskilled youth employed labor force: those with little or no education (zero to primary level); and those with reasonable exposure to the schooling system (secondary and above).

The first category is recognised under SDG target 4.6 that seeks to ensure that by 2030 all youth and a substantial proportion of adults, both men and women, achieve literacy and numeracy. The main challenge is to impart basic literacy and numeracy skills to this labor force through publicly funded programs. The governments Non-Formal Education (NFE) program seeks to address this skills gap. Despite progress, there is still a large unfinished agenda. The major challenge is to convert the NFE into a concept of lifelong learning. Widespread use of ICT resources for organised lifelong learning (e.g., through a nationwide network of community learning centres) and expanding self-learning opportunities, have to be key features of non-formal education and lifelong learning. Adequate funding and organization support based on partnership between NGOs, local community, ministry of education and local government officials are necessary.

For the second category, the main task is to impart them with relevant on-the-job training in strong partnership with the business sector. A strategy for public-private partnership for on- the- job-training scheme can be developed, where the public sector provides the funding while the private sector imparts the training. There are two strands of this strategy. The first element concerns partnership with enterprises in the formal sector. The second element should be geared to addressing the training needs of youth who are employed in informal sector, who are self-employed, who belong to the NEET group, and who are looking for international migration opportunities. The large bulk of the youth is in this category. The most promising option for this group is to enter into partnerships with the donor community and the NGOs. The common principle should be to provide training that will lead to employable skills related to market demand.

Ensuring education and training for all. The SDG Goal 4.5 seeks to eliminate by 2030 gender disparities in education and ensure equal access to all levels of education and vocational training for the vulnerable, including persons with disabilities, Indigenous peoples, and children in vulnerable situations. While there are numerous government policies and regulations, the main challenge moving ahead is to implement these policies strongly and to monitor progress. The government should require concerned line ministries to monitor progress and present to the cabinet annual progress reports for review.

Addressing the challenge of the NEET. The NEET stock presents a complex challenge. This is not simply a matter of providing better training. A whole host of measures including upgrading of education quality, protecting girl child and female workforce, strengthening economywide employment prospects and improving financial access of the poor to institutional sources will be necessary. Some immediate policy actions include:

First, according to LFS 2024, an estimated 68 per cent of the NEET are women. The tougher implementation of the child marriage and prevent of violence against women laws, and the elimination of gender gap in access to tertiary and vocational education will be major steps to reduce the female entry to the NEET group. Second, the implementation of the 12 years universal compulsory education will help reduce the NEET population substantively. Third, quality enhancements in education and training discussed above will help reduce the incidence of both the unemployed youth and the NEET population. Fourth, the government can develop an outreach scheme in partnership with NGOs that provides incentives to the existing NEET population to actively participate in employment-based training schemes. Finally, the promotion of self -employment schemes can play a catalytic role in lowering the incidence of NEET.

Promotion of Youth Self-Employment through Entrepreneurship: The best prospect for creating employment opportunities for the youth in the short term is by promoting self-employment through entrepreneurship.

Non-ICT based self-employment. The MSEs are the dominant source of non-farm employment. Therefore, policies to promote MSEs noted above can also facilitate the growth of self-employed youth. However, special efforts will be needed to jump start the self-employment prospects of the existing cohort of unemployed and NEET youths. Two specific measures will be required. First, action will be needed to impart them with training for entrepreneurship. The government can enter into partnership with the donor and NGO communities to impart these types of training. Second, access to credit will have to be ensured. Enhancing access to institutional credit for individual entrepreneurs and small business is a fundamental development challenge facing Bangladesh and is among the most pressing policy reform for job creation.

ICT-based self-employment. For the educated youth, the best option would be the promotion of ICT based self-employment. The demand for ICT skills is huge and a thriving ICT-based self-employment in a range of services including web design, mobile financial services, e-commerce, and transport has emerged. The dynamic potential of self-employment for youth based on ICT is best illustrated by looking at the progress with the global online labor market, also known as “freelancing and gig working via internet platforms.” The online labor market based on internet websites has grown rapidly across the globe. The online labor platforms match buyers and sellers to deliver a range of services that can be done remotely using internet. Examples of these services include software development, data entry, translation, multi-media, sales and marketing support and professional services. A unique characteristic of the online labour market is that the work is transnational. This essentially means the online worker need not be constrained by domestic demand and can actively bid for online demand globally.

To enable the full potential of the ICT-based self-employment option, a number of policy reforms are needed. The most important is the access to institutional credit, as already noted. The second policy measure is to accelerate the growth of ICT infrastructure and ICT-based services by sharply reducing the large taxation of the ICT sector. This will boost private investment in ICT infrastructure and supply of ICT services while supporting the demand for internet and smart phone services by lowering their prices. Third, the regulatory framework for self-employed ICT specialists and other ICT-based services must be made conducive to their growth. The registration and licensing requirements for web-designers, e-commerce and ICT-based transport service providers must be simple and low-cost. Foreign currency regulations need to be simplified to enable retention and accounting for earnings from international i-labor services. These should be treated at par with remittance income from migrant labor. Furthermore, the tax filing requirements should also be simple and hassle free.

International Migration: Bangladesh has benefitted tremendously from its large pool of legally migrant labour both in terms of job creation and huge inflow of remittance income. The youth population has been a key beneficiary of international migration. Policies relevant to developing the migrant labor force participation, such as training, cost-reduction of migrant labor supply, availability of loans to pay for the migration process, availability of information, as well as policies to ensure labor safety and protection from exploitation will also benefit the youth population.

Labour Market Information: When jobs exist, youth can be helped by providing information and employment exchange services through educational institutions, or by offering these in youth centres. The use of new technologies, particularly mobile phone based, could help in expanding job search networks for youth, linking formal and informal networks, and increasing the effectiveness of these networks.

Monitoring and Evaluation: A major policy reform is the need for a results-based monitoring framework (M&E) with specific quantitative targets to measure progress with implementation. As a part of this M&E framework, the NPFYE must target progress with reduction in the incidence of unemployed youth and the share of NEET youth as suggested in Table 1.

Dr Sadiq Ahmed is Vice Chairman of the Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh (PRI). sadiqahmed1952@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.