Published :

Updated :

I have little trust in my memories. For instance, once, I was convinced that a closely related elder brother (not a sibling) of Sukanta first brought a manuscript of poems and later on introduced the teenage poet (Sukanta Bhattacharya) to me. Following the split in the party (Communist Party), Sukanta’s close circle claimed in writing that it was a lie and they proved it by quoting from Sukanta’s letters. Silence maintained by the senior members of the poet’s family corroborated their claim.

However, I did not have to face any trouble till now while relating my personal memory of Poet Farrukh Ahmad here and there.

Recently, on receiving a 700-page voluminous anthology titled Farrukh Ahmad: Byakti O Kabi (Farrukh Ahmad: The Man & The Poet) and edited by Shahabuddin Ahmad, rekindled the same memory of the past. [The book was first published by Islamic Foundation Bangladesh, Dhaka in 1984.]

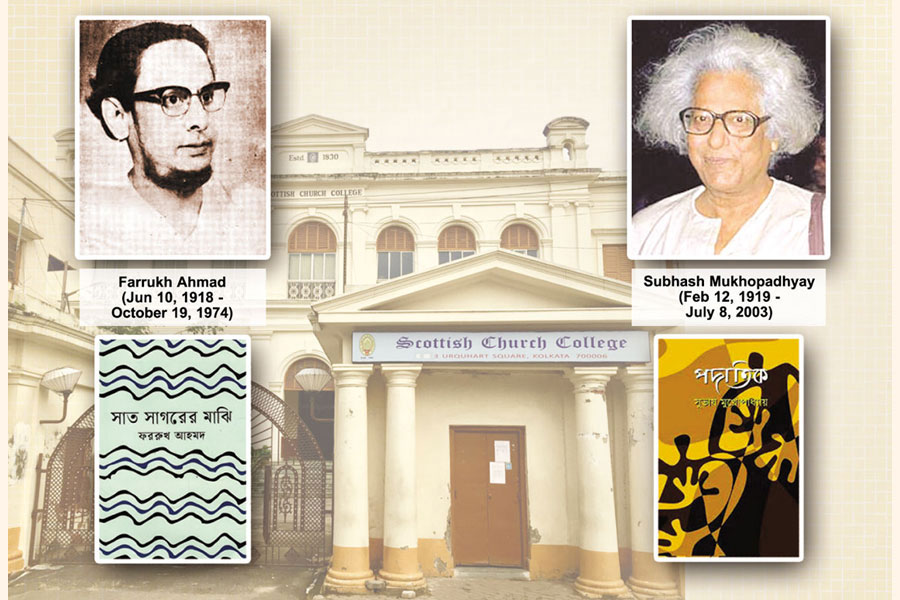

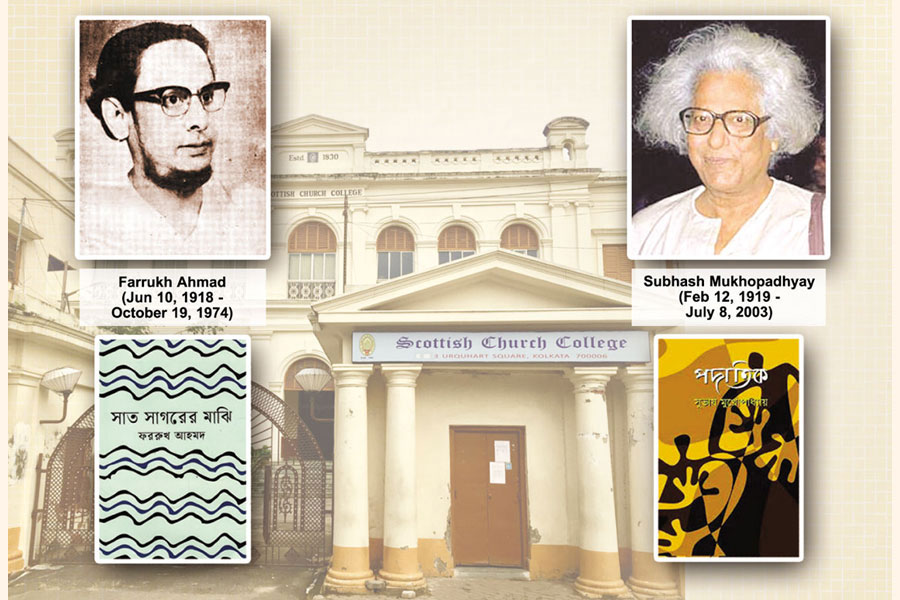

Nothing big at all! Yet there was something funny. The year was 1939, if I am not mistaken. A good number of writers-cum-professors at that time taught at Ripon College (in Kolkata). Writings of some of their students started getting published in newspapers and magazines. All of them including Farrukh, Abul Hossain and Golam Quddus were my contemporaries. I was leaving the Asutosh College for the Scottish Church College to pursue BA (Hons) study. Somehow, I heard that Farrukh was also leaving for the Scottish and his subject too was Philosophy. So, from the beginning, my target was to find him out.

Just took a seat before the start of the philosophy class. But I was looking around restlessly. At Scottish, the seating arrangement had a gallery pattern. The professor was yet to enter the classroom. Someone was sitting right behind me on the next bench. Looking at him, I felt something different. A sharp look was there. My intuition told me it might be Farrukh. But there was no way to be certain.

Turning back, I asked: “What is your name?”

It was beyond my imagination that the boy would intemperately respond, “What business do you have to know my name?” I had made quite a name by then. Padatick, my first poetry book, was about to be published. I was taken aback at first. Then, I made up my mind to see the end of it. The youth could not be other than Farrukh!

At that time, Farrukh’s poems regularly appeared in Kabita, Parichoi and Chaturanga. So far, I can remember, all of those were poems of love, mostly sonnets. I made up my mind. Suddenly turning back, I snatched his exercise book and saw that on the cover of it was written F Ahmad in English.

I felt elated, as I guessed rightly. Again, I turned back and asked him, “Are you Farrukh Ahmad?”

“No,” the reply came in the same impudent tone.

The logical outcome of this could be the emergence of a silent wall between two conceited poets. In reality, the opposite happened. Farrukh became my most intimate friend in college.

One day, Farrukh prevailed on me to accompany him to their house. So far as I can remember, it was right on an unpaved road across the rail track in the east. A tin-roofed house. Herbs, shrubs and bushes were all around. A big courtyard inside. After a while, arrived tea accompanied with a round-shaped mumlet prepared from eggs laid by their domestic hens. I can still feel the taste of the mumlet. After that ambrosia, poison wrapped in brownish leaf of the little finger-size was shoved into my hand. Then he lit it with a match stick and asked me to inhale. Thus did I get enamoured forever with the charm of bidi subjected in general to disdain in gentlemen’s drawing room.

After college education, we were drifted in two different directions. I received news about Farrukh from different sources. Heard that he had changed a lot. He used to spend nights on a park bench at times. His sophistication in dress was gone. His writings in Kabita, Parichoy, or Chaturanga were also conspicuous by their absence.

Suddenly, once I met him at the Azad office in Kolkata. With a small patch of beard under the chin, he had a Panjabi not so clean on and pyjamas instead of a dhuti. Thin, as usual. Can’t remember whether he gave up bidi, cigarette at that time. But his mouth was always full of betel leaf and in his hand was its petiole with lime paste at one end. He beckoned me to follow him to the veranda.

“Are you not writing poetry anymore?” I asked.

“Hush! I am now the poet-laureate of Muslim League,” he replied. Then glancing at some League students standing at a distance out of the corner of his eye, he said, “ Don’t you understand, I am keeping them in good humour?”

Occasionally, Farrukh would surreptiously come to the office of the Swadhinata Patrika on Dacres Lane to see me. It was pleasing to see that he did not forget me at all.

However, if any of the progressive Muslim youths found him, trouble brewed. They used to curse him and I was also not spared.

Then came independence and with it the partition of India. At one point, I learned that Farrukh had migrated to Dhaka. Before he left for Dhaka, we had not met for a long time.

Immediately after the Language Movement in 1952, I went to Dhaka to attend a literary conference. Enquiring about Farrukh, I was met with a rebuff from my acquaintances —-hurried to avoid the question, saying, “Don’t Know”. Once I visited the Dhaka radio office, where I expressed my desire before a few young writers to see Farrukh.

In a hot temper, one of them asked: “What business do you have with him?”

“He is my friend, we have studied in college together,” I replied.

“It is incomprehensible how such a diehard reactionary could be your friend? No, you better not met him.”

I was in a great dilemma. Now Farrukh a religious fundamentalist—-what do they say? Impossible! He may have angered people here as well by his straight talks.

Right then, a little boy came and gave me a chit with the note, “I am in the adjoined restaurant. You skip them and come here—-Farrukh.”

As soon as I arrived at the specific restaurant, dodging the young writers against my will, Farrukh said, “I knew they would not allow you to meet me. These young chaps can’t write anything. Famous for tall talks only! ”

“Why are they so angry with you?” I asked.

“Oh... leave them alone.”

Then Bangladesh became independent in 1971. The same happened. More serious complaints now against Farrukh —-levelled by Zahir Raihan. I am hard put to accept such a charge. If true, he could easily move to Pakistan. It’s not that he had no time. It is, however, such a matter about which I am not competent enough to say anything for certainty.

Yet what I can assert is that orthodox Islam attracted Farrukh which he tried to hide from me. Sat Sagorer Majhi (The Sailor of Seven Seas), is the outcome of this overwhelming inspiration. His writings have gone through a sea-change under this influence. His love poems composed in his youth appear to be shallow compared with those writings.

The melody of whose flute made Farrukh rush headlong, I don’t know; but the sweet cadence of the anklets of his dancing feet will pour sweetness into our ears forever.

Whether Farrukh misunderstood the country and the time or the latter the former, the defendant’s death before the verdict has led to the dismissal of the case.

[The piece, originally written in Bangla was first published in Kolkata-based Fortnightly the Protikkohon and later reprinted in collected works titled Farrukh Ahmad. Published by Seba: Sahittya, Sangskrit Janayakalyan Sangstha in 1987, the compilation included the piece but did not mention the original source. So the original date of publication is still unavailable. The English version is prepared, following the reprinted piece, by Asjadul Kibria and edited by Nilratan Halder.]

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.