Fiscal balance of Bangladesh: six key areas of policy interests

Published :

Updated :

The fiscal framework of Bangladesh has shown signs of considerable stress all through the ongoing fiscal year (FY23). This has been manifested in, inter alia, subdued growth in revenue mobilisation, slow implementation of the annual development programme (ADP), and increased reliance on bank borrowings to finance budget deficit – particularly from the central bank. The government also had to resort to an IMF-supported programme in the backdrop of discernible macroeconomic instabilities. The key objectives of this support programme include enhancement of revenue mobilisation, reduction of NSD certificate issuance, containment of subsidies, and increase of public expenditure efficiency with fiscal and institutional reforms. It must also be mentioned in this regard that the IMF programme comes with a set of time-bound milestones and conditionalities; the extent of availability of the support will hinge on Bangladesh’s ability to meet those. Such conditionalities, on the one hand, will provide some form of policy predictiveness. On the other, these will entail some hard choices on the part of the policymakers. In this backdrop, the present chapter spotlights some key areas that require urgent policy attention.

Major Observations on the Fiscal Framework: Targets of revenue mobilisation for FY23 will be missed by a large margin. The revenue mobilisation scenario in FY2023 appears to be quite dismal. According to the Ministry of Finance (MoF) data, during July-February of FY23, total revenue collection decreased by (-) 0.1 per cent over the corresponding period of FY22. However, the targeted growth of total revenue for the entire fiscal year was 29.5 per cent. This implies that an unprecedented 98.3 per cent growth will be required during March-June of FY23 if the target of revenue mobilisation is to be achieved. According to the MoF data, revenue collected by the National Board of Revenue (NBR) decreased by (-) 1.3 per cent during the July-February period of FY23. Since NBR is tasked to mobilise more than 85 per cent of the total revenue envelope, this state of collection undoubtedly points towards a large shortfall in revenue earnings (i.e., the gap between targeted and actual revenue mobilisation) at the end of the fiscal year. Indeed, CPD in March 2023 projected that the total revenue shortfall (including tax and non-tax) at the end of FY23 would be approximately Tk 750 billion. Hence, it can be said with certainty that it is not possible to attain the ambitious revenue mobilisation targets set out in the national budget for FY23 as well as the IMF conditionality.

Full utilisation of the budgetary allocations remains elusive. The inability to deliver on the programmed budgetary allocation has continued in FY23. During the first eight months of FY23, only 37.6 per cent of the total budgetary allocations could be utilised. The corresponding figure for FY2022 was 38.3 per cent. Alarmingly, annual development programme (ADP) expenditure fell both in terms of monetary value and implementation rate during the aforementioned period as far as the MoF data is concerned4. The utilisation rate of non-ADP expenditure rose albeit significantly, from 47.5 per cent during July-February FY22 to 47.9 per cent during July-February FY23 – indicating a 15 per cent growth. This was driven primarily by increases in expenditure owing to interest payments, subsidies, incentives, and current transfers. Due to the depreciation of the Bangladeshi Taka (BDT), the expenditure incurred for interest payments is likely to face upward pressure during the remainder of FY2023.

While the budget deficit widened, the composition of deficit financing has become a more problematic issue. According to the MoF data, in the first eight months of FY2023, the budget deficit (excluding grants) reached Tk. 212.01 billion compared to the budget surplus of Tk. 29.37 billion in the corresponding period of FY22. Net sales of National Savings Directorate (NSD) certificates decreased by 63.4 per cent during the July-February FY2023 period thanks to reduced interest rates and additional regulatory requirements, including the obligation to provide income tax return submission receipts. Net borrowing from the banking sector, including the Bangladesh Bank, increased by nearly 70 per cent during the aforementioned period. Net foreign financing has declined by 24.8 per cent during the first eight months of FY2023, and the government has sought increased budget support from multiple development partners for FY2023.

Six Key Areas of Policy Interests: NBR will need to identify new sources to mobilise the required revenue. Enhanced economic activities will induce natural growth in revenue collection. To find out its extent, an OLS estimation was carried out. The model considered is provided in the following equation.

From the estimation, it was found that a one per cent increase in real GDP and import will increase the tax revenue collection by 0.59 per cent and 0.65 per cent, respectively; the coefficient values are positive and statistically significant. On the other hand, the coefficient for inflation is found to be negative (-0.02) and statistically significant. This implies that a one per cent increase in inflation will result in a decrease in tax revenue collection by 0.02 per cent. As have been reported in several media outlets, targeted GDP growth and anticipated inflation in the upcoming FY2024 are 7.5 per cent and 6.0 per cent, respectively. Also, IMF projected that imports would increase by 14.2 per cent in FY2024. If these values are taken into consideration, then using the aforesaid coefficients, it can be forecasted that the tax revenue collection in FY2024 will increase by 13.5 per cent. As previous experience shows, growth targets of revenue mobilisation for a particular fiscal year are set considering the revised budget figures of the previous fiscal year. However, if the actual collection of the previous fiscal year is taken into account, then the growth targets for the following year become much higher. This ultimately contributes towards a considerable amount of revenue shortfall. If the potential shortfall in tax revenue is considered, the likely target will be expected to generate around 37-40 per cent growth. This implies that a natural course of action will not work for the government, particularly with respect to the NBR. Hence, it can be unambiguously stated that, without new sources, the revenue shortfall will remain very high and will constrain the fiscal space significantly. As has been reported in the media, the government is planning to, inter alia, raise taxes on cigarettes, introduce some form of a carbon tax, impose a minimum tax on individuals who will file tax returns even if they do not have taxable income, increase capital gains tax, impose VAT on mobile phone at the manufacturing stage etc. More potential sources of revenue collection, such as property tax, inheritance tax, and taxes on digital economic activities, can be explored7, not to mention going for better enforcement to deal with tax avoidance and corruption in the system.

Strategising rationalisation (gradual withdrawal) of tax exemption provisions will need to be objective. CPD has long been urging the need for rationalisation of tax exemptions which have become rampant over recent years. As part of IMF conditionalities, reduction of exemptions in the areas of income tax, VAT, and customs will have to be carried out. The extent and sequencing of the withdrawals will be key in balancing the needs of meeting the conditionalities and supporting domestic industries. There are many debates that inform the discourse concerning the provision of tax exemptions. In an ideal situation, all types of tax exemptions should respond to well-defined and clearly articulated policy objectives. However, in reality, this is often not the case. In some instances, certain exemptions benefit only the target groups instead of the whole society. In some cases, the exemptions may have been beneficial at the time of their introduction but, over time, lost their relevance in the wake of declining social returns. Many tax exemptions are introduced to appease various interest groups rather than to meet actual needs. This results in significant efficiency loss. In Bangladesh, many exemptions are not time-bound, and those that have time limits keep getting extended. Thus, a medium-term plan and timeline to phase out the various tax exemptions have emerged as an exigency. The next budget should lay out an action plan to this end. Some fundamental questions ought to inform this phasing-out process: whether new or existing sectors should be prioritised; whether export-oriented or domestic market-oriented industries should be prioritised. Whether households or businesses should be prioritised? The policy related to the rationalisation of tax exemption provisions should not be left to the vested interest groups and should prioritise small and medium businesses and general people.

The guiding principles behind the austerity measures should be clear. The government has already taken some austerity measures, which include expenditure cuts across the sectors and not undertaking new expenditures. In the FY2023 ADP, projects were divided into A, B, and C categories based on priority to ensure proper utilisation of limited resources. The A-category projects were planned to be implemented as usual, while up to 75 per cent of the allocation for the B-category projects could be spent. All C-category projects were put on hold. However, some of these restrictions were relaxed later. Whether the proposed categorisation was followed in view of the austerity measures remains a question. An account of cost savings owing to the categorisation of ADP projects and subsequent implementation can be provided in the FY2024 budget to bring some clarity. CPD, in December 2022, urged the government to prioritise the implementation of all foreign-funded projects in view of the foreign currency crisis. At the same time, projects which are closer to completion also needed to be prioritised. An incentive mechanism, following a carrot-and-stick principle, could be introduced to facilitate the timely implementation of ADP projects. It needs to be ensured that project costs are not abnormally inflated, citing the devaluation of the BDT as a reason. Finally, the austerity measures should be taken in a way that the impact on the social safety net, health and education sectors, agriculture, and small and medium enterprises (SMEs) is less onerous.

Prioritisation, pacing, and consideration of distributional impacts will be key in case of subsidy management. Adequate subsidies in the agricultural sector, particularly for fertilisers and pesticides, will need to be ensured. As the international commodity prices have come down, budgetary allocation for agriculture and food should be lower than the ongoing fiscal year; and hence, should not be a major concern. Indeed, a review of the agricultural subsidies will be necessary to see if such incentives can be extended beyond foodgrains and to other promising rising areas of agriculture, particularly in view of the ongoing commercialisation of agriculture. Food subsidy, if required, may be increased to expand public food distribution in the backdrop of high prices of essentials which should be directed towards the disadvantaged population groups in need. The current provisions of the fiscal incentives towards exports and remittances should be maintained to start with. However, exit plans will need to be formulated in both cases. For example, if the exchange rate is made market-based, the resultant depreciation should cover the fiscal incentives provided now. This is also true for export subsidies. While allocating the budget, the possible impact of a future depreciation of BDT needs to be taken into cognisance.

The most critical policy decisions in the areas of subsidy will need to be in the energy and power sectors. If the periodic formula-based price adjustment mechanism for petroleum products is adopted as per IMF suggestion, then no subsidy will be required for Bangladesh Petroleum Corporation (BPC). To this end, there is a need to review the tariff and tax structure. An institutional audit of BPC should be carried out to ensure transparency and accountability. Currently, of the retail selling prices of diesel (Tk. 109/litre) and octane (Tk. 130/litre), the government collects about 17-18 per cent as customs duty, VAT, advance income tax and advance tax. According to media reports, the government is considering the withdrawal of advance tax (5 per cent). However, this may not have an impact on the retail price as paid advance tax at the import stage is adjusted with the VAT collected at the domestic stage. According to CPD’s estimation based on available information, BPC is likely to make profits to the tune of about Tk. 5 per litre from selling a litre of diesel and about Tk 13 per litre from selling a litre of octane. So, there may be an opportunity to reduce petroleum prices between Tk. 5-10/litre. It is to be noted that the windfall gain made by the BPC comes at the price of consumers’ reduction in purchasing power. Indeed, BPC’s total profit in the last seven years (FY16-22) was about Tk 438.04 billion. After paying Tk 77.27 billion as income tax to the government, the total net profit of BPC over the said period (FY16-22) was Tk 360.74 billion. Being a monopoly in the sector and as it is a state-own enterprise, penalising the citizens of the country cannot be justified. As the government may opt for a periodic formula-based price adjustment mechanism for petroleum products, the pricing mechanism, tax policy, and profits should be analysed publicly, objectively and transparently. Indeed, the government is also collecting additional revenues from the windfall gains of BPC as VAT and income tax. The windfall gains of a (state-owned) monopoly should not be considered as ‘value-added’ on which VAT is to be imposed. Also, income tax is collected from the profit originating from the windfall gains of BPC. Indeed, with reduced prices of petroleum products, the demand for subsidies for the power sector will also decline. The subsidy on power cannot be phased out overnight, given the inflationary effect of the power price rise8. Power sector subsidies should be rationalised not only by the upward revisions of electricity prices but also reducing the burden of capacity payments provided to IPPs and quick rentals. At the same time, the energy mix for power production and the associated deals in the power and energy sector will have to be scrutinised further. There must be a pathway to phase out of the costly quick rental power plants. The next national budget for FY2024 should refrain from making budgetary allocations for subsidies (or loans) to other state-owned enterprises.

A rethinking regarding the classification of social safety net programmes (SSNPs) is necessary if their expansion, both in terms of coverage and rates, is to be carried out in a transparent and meaningful way. Valid concerns remain regarding the transparency of SSNP implementation. Publicly available data only shows targeted coverage and allocation but never the actual implementation figures, which hinders comprehensive evaluation and understanding of their impact. One matter of contention is the inclusion of loosely related programmes that inflate the total number of SSNPs and the concerned budgetary allocations. While it can be argued that fringe elements need to be included to make a comprehensive list, the inclusion of completely unrelated programmes (e.g., pension for retired government officials, agriculture subsidies, various credit programmes, infrastructure projects etc.) raises questions as to whether the intention was to inflate the statistics in the first place.

In this context, CPD has classified the different SSNPs for FY10 and FY23 into three categories viz. compatible (i.e., the SSNPs that should naturally be included in the aggregate list), quasi-compatible (i.e., those that fall somewhere in the ‘grey’ area), and non-compatible (i.e., those that should be excluded from the SSNP list). In FY10, the number of compatible, quasi-compatible, and non-compatible SSNPs was 40, 17 and 10, respectively. The corresponding numbers for FY23 increased to 57, 29 and 29, respectively. Compatible SSNPs constituted 62.2 per cent of the total SSNP budget in FY10, whereas the corresponding share was 29.7 per cent in FY23. In contrast, the share of non-compatible programmes in the total SSNP budget increased from 25.5 per cent in FY2010 to 56.5 per cent in FY2023. If pension for retired government employees is not considered, then the situation becomes even worse – the share of non-compatible programmes rising from 5.8 per cent in FY10 to 42.3 per cent in FY23. Indeed, the allocation for the compatible SSNPs as per cent of GDP declined from 1.6 per cent of GDP in FY10 to 0.8 per cent of GDP in FY23. As a share of the total national budget, this declined from 9.5 per cent in FY10 to 5.0 per cent in FY23.

If the government continues to borrow from the central bank, it will further deteriorate the macroeconomic discipline.

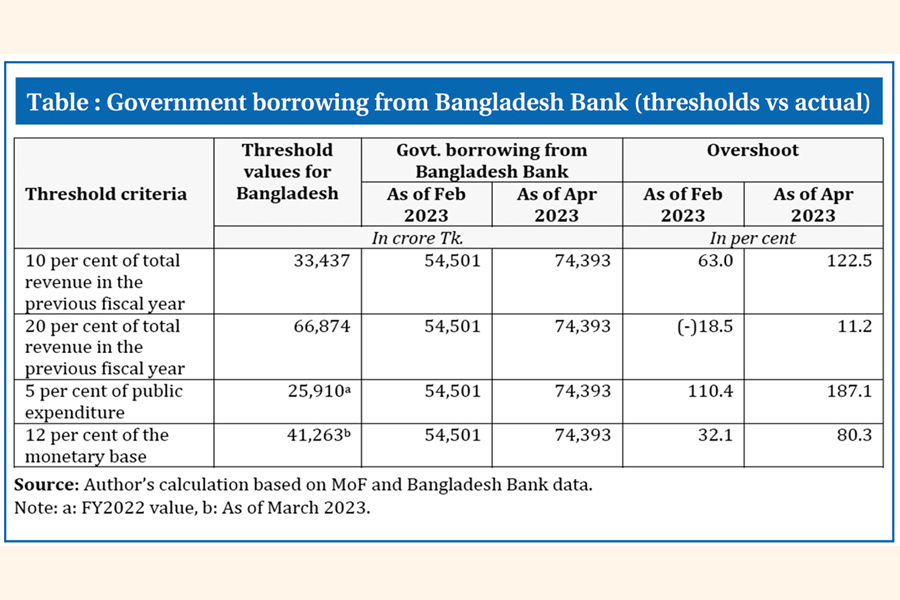

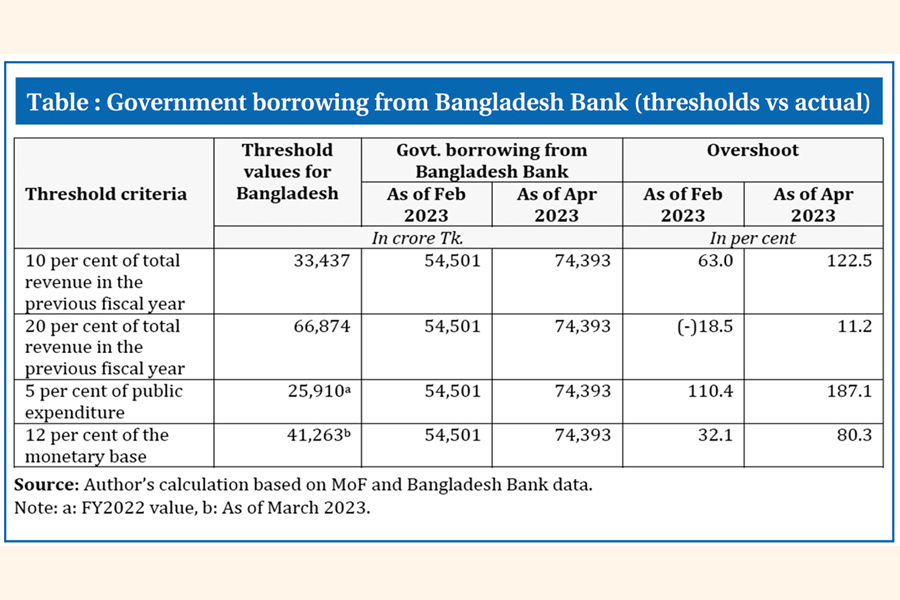

It can be argued that the government can run a perpetual budget deficit, paying interest accrued on the growing debt load simply by issuing new debt. However, this is far from reality, as the government is bound by a number of constraints. Both governments and central banks face structural constraints that limit their financing possibilities; going beyond a certain limit may result in explosive debt growth or serious inflationary problems. A cross-country literature survey reveals that country practices vary when it comes to limiting the central bank’s credit to the government. A universal golden rule or limit is perhaps elusive. However, many countries have put legislative limits to this end. Most countries cap credit, overdrafts, or advances to less than 10 per cent or, at best 20 per cent of the government revenue in the previous fiscal year. Alternative relative measures are also applied by a few countries to limit government borrowing from the central bank, for instance, 5 per cent of government expenditure in Costa Rica or 12 per cent of the monetary base in Argentina.

As of February 2023, the government’s borrowing from the central bank stood at Tk 545.01 billion. If media reports are taken into consideration, then this figure reached as high as Tk 743.93 billion in April 2023. A comparison between the aforementioned thresholds and the actual government borrowing showed that the government’s borrowing from the central bank surpassed all the thresholds for each criterion by a considerable margin. Indeed, it is apprehended that during the last quarter of the fiscal year, government borrowing will increase further (as it happens every year) as the demand for financing the budget deficit tends to rise. With limited funding available from other sources (i.e., foreign borrowing, non-bank borrowing and borrowing from commercial banks), the government will continue to borrow from the central bank if no discipline is applied. Curiously, the central bank has not made any clear policy stance to this end. Given that borrowing from the central bank is high-powered money, it has an inflationary impact on the economy. Applying the money multiplier (5.15 as of March 2023), the borrowing from the central bank so far (as of April 2023) may have created about gross new money to the tune of Tk. 3.83 trillion. Thanks to net sales of foreign exchange (resulting in a decline in foreign exchange reserve), the net foreign assets declined, which helped to keep the broad money growth in check. However, the central bank is no longer in a position to continue such release of foreign exchange reserves. Indeed, the government will need to build up foreign exchange reserves in the coming months, including throughout FY24, which will release more money in the market. At the same time, in FY24, there is an apprehension that borrowing from the central bank to finance the budget deficit may continue, particularly if the interest rates remain administrative. Hence, continuing borrowing from the central bank will surely create a higher flow of money supply and hence, create inflationary pressure. This inflationary impact, in turn, may deteriorate the balance of payments scenario by creating more aggregate demand. It will also be critical for the government to mobilise the foreign-funded budgetary support under negotiation with several multilateral funding agencies.

Dr Fahmida Khatun, Executive Director, Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD); Professor Mustafizur Rahman, Distinguished Fellow, CPD; Dr Khondaker Golam Moazzem, Research Director, CPD; Mr Towfiqul Islam Khan, Senior Research Fellow, CPD, (towfiq@cpd.org.bd); Mr Muntaseer Kamal, Research Fellow, CPD, (muntaseer@cpd.org.bd); Mr Syed Yusuf Saadat, Research Fellow, CPD.

[The authors received research support from Mr Abu Saleh Md. Shamim Alam Shibly, Senior Research Associate; Mr Foqoruddin Al Kabir & Ms Nadia Nawrin, Research Associates; Ms Maesha Rashedin Joita, Ms Lubaba Reza, Mr Mohammad Abu Tayeb Taki and and Mr Mahrab Al Rahman, Programme Associates, CPD.]

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.