Published :

Updated :

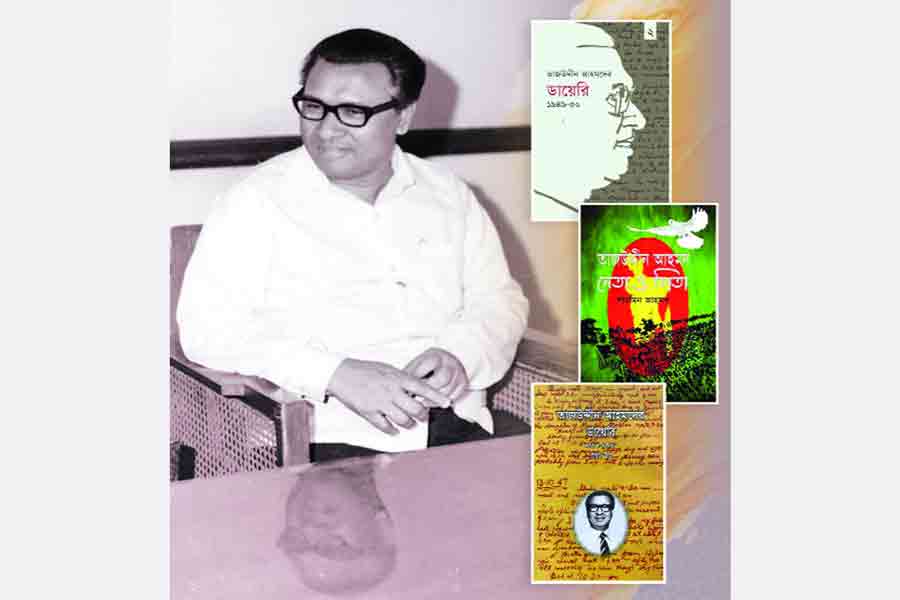

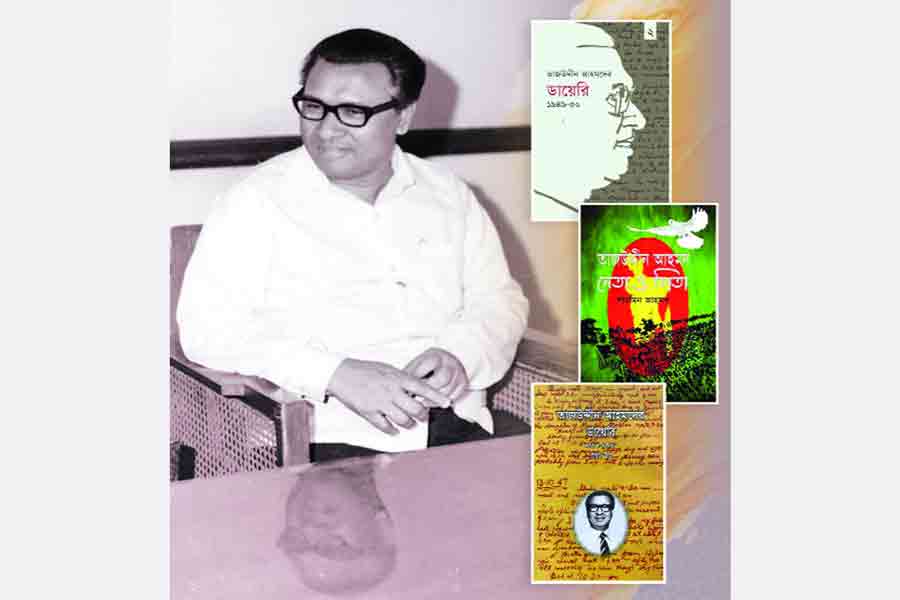

Tajuddin Ahmad would be a centenarian on 23 July. He was a mere fifty years old when he was assassinated in November 1975. Yet in those brief five decades of his life, he achieved a feat rare in the history of political men. He rose to the peaks of leadership in the brilliance emitted by Bangabandhu and remained there till almost the very end. In between, he managed to pull off what was certainly the most significant success in its long socio-political narrative for the Bengali nation, the formation of the very first Bengali government in history and the liberation of Bangladesh. That was his moment of glory.

In recent years, a necessary revival of interest in the life and career of Tajuddin Ahmad, given the callous and deliberate manner in which he has been ignored by the post-1975 Awami League leadership, has served to add the missing links to Bangladesh’s national history. Much of the revival is again a result of the strenuous efforts put into the story of the wartime leader by his daughters Sharmin Ahmad, Simeen Hossain Rimi and Mahjabin Ahmad Mimi. They have had Tajuddin’s life, in the form of biographies, letters and diaries, researched and transcribed in Bangla and published in immaculate form. Add to the story Tanvir Mokammel’s remarkable biopic, ‘Tajuddin Ahmad: Nishshongo Sharothi’, on the nation’s first Prime Minister.

Maidul Hasan’s Muldhara ’71 and Faruk Aziz Khan’s Spring 1971 have additionally highlighted the intellectual politics Tajuddin Ahmad brought into play in steering the nation to victory on the battlefield. The Mahbub Karim-edited Tajuddin Ahmad: Neta O Manush’ and Badruddin Ahmad’s Muktijuddher Mohanayok Tajuddin Ahmad have been commendable appraisals of the great man’s life and career. These works are touching tributes to the humble, austere man who has, especially since his assassination in 1975, become an icon for students of history. They have offered his legacy anew to a nation that might well have been blown off course had he not been around to take charge.

Back in March 1971, the risk for Bengalis was double-edged. On the one hand was the reality of Bangabandhu’s captivity at the hands of the Pakistan army. On the other, there was no clear sign of anyone else in the Awami League hierarchy, at least up to that point, taking control and reassuring the country that everything was on course, or soon would be. The call of duty was one that Tajuddin Ahmad heard loud and clear. By the time he crossed the border, he knew that exile, his and that of everyone else in those times of horror, would need to be purposeful. He lost little time in linking up with Indira Gandhi and laying out before her his plans of Bangladesh’s road to liberation.

Tajuddin could not have been happy, post-liberation, at being relegated to the job of Finance Minister once Bangabandhu took charge as Prime Minister, but his acute sense of loyalty precluded demonstrating any hint of his displeasure. Discipline was a lesson he had learned early on in life. He was not inclined to verbosity. He was not an orator. It was his organisational abilities which complemented the inspirational leadership of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. These two men, more than anyone else in the party, were the reason why Bangladesh needed to be. On their watch in the early 1960s came the Six Points. In early March 1971, as Yahya Khan and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto resorted to chicanery, it was deep-rooted Mujib-Tajuddin strength that kept them at bay, until the junta unleashed the dogs of war.

That was not the only tragedy. Somewhere between cobbling the Mujibnagar government into shape in 1971 and making his way out of government in 1974, Tajuddin was a lonely, persecuted traveller. Sheikh Fazlul Haq Moni and his band of Young Turks undermined the nation’s first Prime Minister in 1971 even as he defined military and political strategy for a nation at war. There were other troubles as well. Tajuddin had constantly to look back, behind his shoulder, for there was an odour of conspiracy in Khondokar Moshtaque. Tajuddin’s loneliness took on newer dimensions in early 1972. The men who had never forgiven him for taking control of the liberation struggle now drove a wedge between him and his leader.

It was Tajuddin Ahmad’s sadness that he could not come by the opportunity to explain to Bangladesh’s founder how he and his colleagues had organised the armed struggle for freedom. It seared the soul in the battlefield leader to know that the Father of the Nation had little time for him. Worrying too for him was Bangabandhu’s move towards a definitive shift in foreign policy. A clear trend towards developing ties with the United States (US) and towards closer association with donor institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) left Tajuddin perturbed. He had studiously ignored Robert McNamara in early 1972. And yet it was McNamara he was compelled by circumstances to meet in 1974, at a time when famine stalked the land and socialism did not appear to hold much promise for Bangladesh.

There was something of the abrupt about Tajuddin’s departure from government. Disillusioned, he spoke of resignation and told perhaps a lot of people about it. In the end, the satisfaction of leaving government voluntarily was not to be his. It was Bangabandhu who asked him, in the larger national interest (as his terse note to Tajuddin pointed out), in October 1974 to submit his resignation. Tajuddin Ahmad complied with the directive. Between that low point in his life and the end of life itself, he would lapse into silence. The assault on pluralist democracy, through the rise of the one-party BAKSAL system of government in January 1975, appalled him.

It was the statesmanship in him that informed him of the tragedy ahead. Conditions were coming to a pass where Bangabandhu would be destroyed, he reasoned, for his enemies were gathering around him, indeed closing in on him in sinister fashion. And with Bangabandhu gone, Tajuddin and everyone else would be pushed towards doom. And that was precisely the way things happened. As he went down the stairway of his residence in August 1975, a man in army custody, Tajuddin told his wife he might be going away forever. He was to return home in November, shot and bayoneted to an ugly death.

It is the quiet legend of the man that was Tajuddin Ahmad which Bengalis have not forgotten. In the darkness that swept across the country on 15 August 1975, there were yet the intimations of light at the end of the tunnel. Someday Tajuddin Ahmad might again take charge, as he had taken charge in April 1971, and restore the nation’s self-esteem? Someday the dreams he and Bangabandhu had forged together in their halcyon days would be born anew?

But that was not to be. That has been Bangladesh’s long agony, its indigenous Greek tragedy, often punctuated by Shakespearean despair.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.