Published :

Updated :

It was not that when the United States entered World War I, prompted as it was by repeated German submarine attacks on civilian ships, it was a completely new contender in the global playing-field. It had already defeated a former global power, Spain, in 1898, and by taking the Philippines, it announced its Pacific Ocean supervision. Nevertheless, declaring war on Germany in April and Austria-Hungary in December 1917 only made for a stuttering start to global leadership that Donald J. Trump's presidency is also stuttering to shutter in 2017. Though his success or failure depends as much on post-1917 US seeds sown as exogenous developments, this might still have been the finest US hour, the true US century.

One of those seeds was the League of Nations, before the United States retreated into its own shell; and though the world body failed in the absence of its dominant creating country, it set the wheels of self-determination/independence and global governance in motion. These completely reconfigured the entire 20th Century landscape: the planet's first 'international' organisation allowed former empire-hunting European countries and their colonial vassals to sit with equal sovereign rights on the same table. Even with the United States as a sine qua non founding member, the United Nations moves on without an active United States today; and even with the Security Council as a pivotal component, the UN family has so branched out that arguably more action happens outside its New York headquarters and Security Council purview than within. In short, so many international forces have been unleashed as to encourage supranational conversations and non-state initiatives, in turn, breeding trans-nationalism, multilateralism, globalisation, and border-permeation as trademark 20th Century themes/symbols/ trademarks in the same way as imperialism and multi-polar balance were of the 19th Century.

Without the United States, these would not have been possible as routinely as they were. It alone picked up the World War II tab so other countries could recover from war, fulfil and consummate independence, and find protection against a snarling communist threat as vicious as the Nazi-ism/fascism that produced World War II were. That was just for starters. It alone encouraged West European countries to group, thus paving the way, not to revive the security-laced 19th Century Concert of Europe, but to produce the economically integrated epoch-making European Union; and it alone unleashed direct foreign investment forces that have dramatically altered the face of this earth. Paraphrasing a well-known Shakespearean phrase, all the corporations in the entire world outside the United States put together cannot match their US counterparts in the resources available, cultivated, or acquired.

Pearl Harbor may have been why the United States returned to the international playing field; but it was not the only causal pathway. An innovative reciprocal trade formula initiated in 1934 not only rescued global commercial relations after the 1930s depression (the longest, widest, and deepest in the 20th Century), but also served as the underpinning of regional economic integration and the multilateral order constructed immediately after World War II.

More than these, the Pearl Harbor attacks made the United States to be what it wished, and was, as if, destined to be: a Pacific power. The same Pacific Ocean that once beckoned the 'westward movement' to California, with all its cowboy stories and gold-digging fables, now seduced the United States into the largest continent, Asia, boasting the largest 21st Century markets and investment recipients.

James Monroe's 1823 reference to Europe as the 'old' continent really put the lid on expansive European power: European colonies began to break away, and though Germany twice tried to build Latin platforms against the United States (the first in 1917, no less; the other during World War II; and both with Mexico), the United States snuffed those efforts, so much so that 20th Century Latin economic growth has tip-toed US pathways far more than European. One of those pathways, the Asian-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), even further downgraded Europe and gave Latin America more robust oceanic outlets than with European countries.

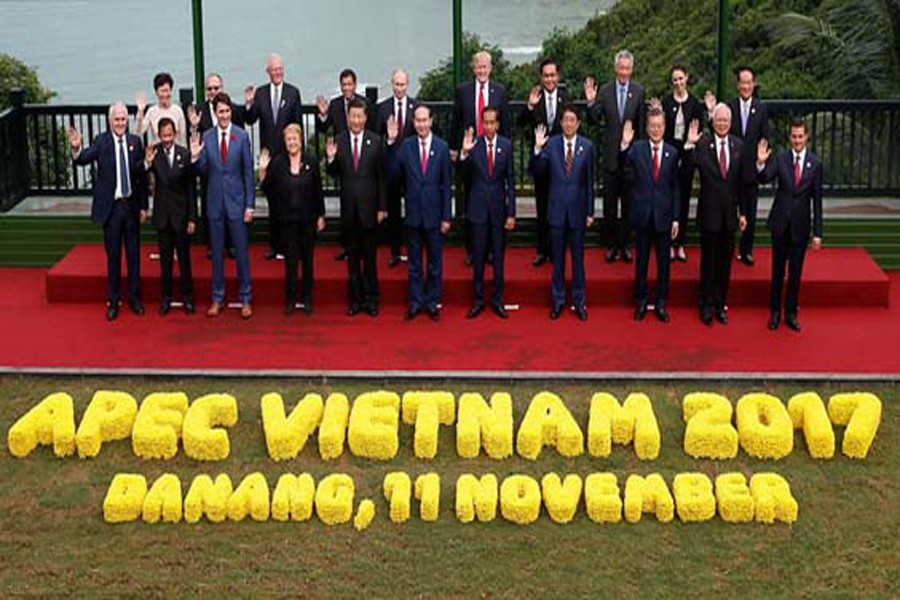

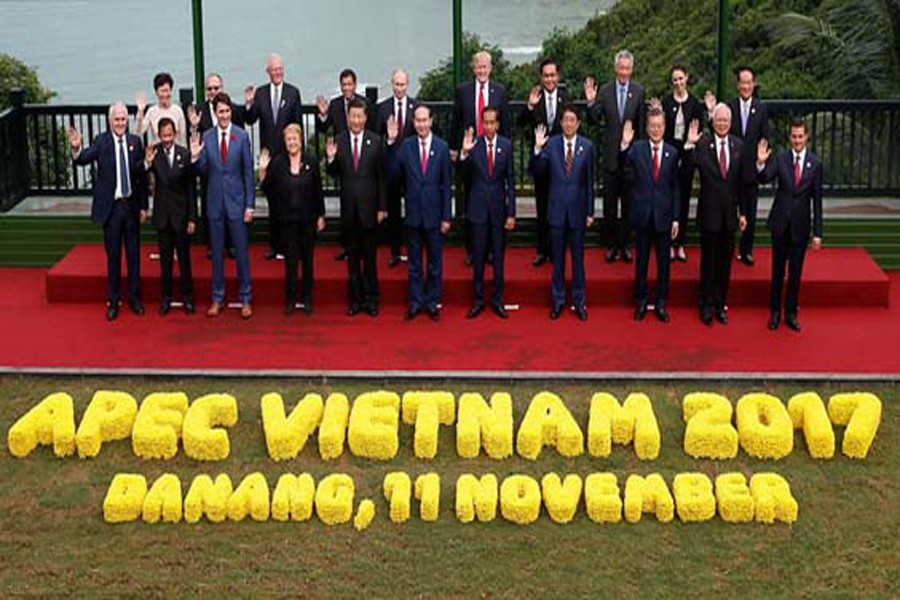

Yet, with Trump's 'America First' slogan, the Americas seem poised to look 'old' instead. His November 2017 Asian visit, no less to the Da Nang 25th APEC anniversary gathering in Vietnam, coupled with the 50th ASEAN (Association of South East Asian Nations) anniversary in Manila, the Philippines, was used to admonish his Asian (trade) partners rather than to open much-needed new frontiers, like the abandoned Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) proposal.

Trump cannot alone pull the leadership curtains for his country: transactional trends, reciprocal sentiments, and a competing political-economic fulcrum also influence that equation. While an Asian power-balance framework spins off from the phenomenal growth of back-watered China into a dominant leadership contender, the US slippage into an 'old' continent mode in the 21st Century does not necessarily mean its sun has set: it still contains enough chips to influence global outcomes, but increasingly through negotiations, not determinations.

Trump may be blamed for his duplicitous or ambiguous policy preferences during this trip (with China, Japan, and South Korea specifically, Asian groupings broadly), but reality may simply be this: his country commands fewer options in that continent than ever before, confronts more competition there than anywhere else, and, most critically, conveys fewer domestic demands/ desires for Asia-based trademarks to reinvent its sturdy Asian policy position. It might learn from Germany and Japan after their 1945 defeat: negotiated outcomes can help a country punch above its weight.

If, at the crossroads, the prevalent wind drives the United States homeward, its first 'old' world reference, that is, across the Atlantic, may make making European countries press the nationalistic pedal even more fervently. Trump's admonishment of so-called NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) free-riders, rejection of the Paris Agreement, and indifference to that continent's dominant personality, Chancellor Angela Merkel, reverses the collaboration parameters Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill identified in the Atlantic Charter, off Ship Harbour, Newfoundland, in August 1941, and embodied in the 1949 NATO institution. If Trump has his way, the Atlantic Charter would follow the Soviet Union into history's dustbin.

Abandoning ties that stood the tests of time and ignoring frontiers that could still be explored are not how leadership is built. Another way leadership has been built is through brute force, as with Germany's Adolf Hitler and the Soviet Union's Josef Stalin. Clearly Trump's United States cannot go this second route. Without retreading the competitive channels of the 20th Century, the mixed 2017 US message is worrisome: the heart to want to carry on as leader is no longer there; but significantly, neither are the perceived resources to do so with.

If it takes one unremarkable leader to end a remarkable global era, then the passé 21st Century United States begs the urgent question if another Wilson or Roosevelt awaits in the wings to squeeze more US leadership juice. Or must we find them elsewhere.

Dr. Imtiaz A. Hussain is Professor & Head of the newly-built Department of Global Studies & Governance at Independent University, Bangladesh.

imtiaz.hussain@iub.edu.bd

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.