Shipbuilding industry in Bangladesh

How experiences of South Korea, Japan, & China may help the country

Published :

Updated :

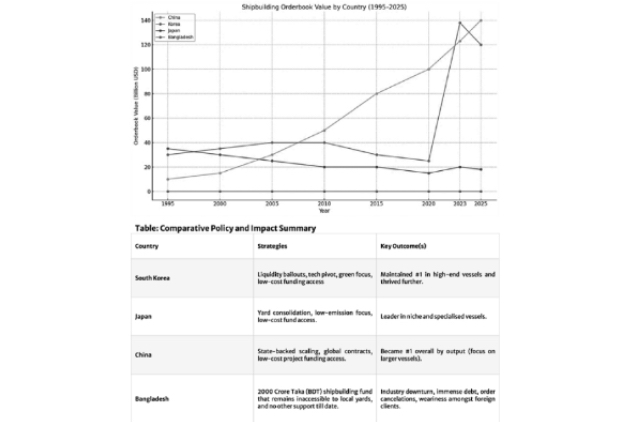

By 2008, South Korea, Japan, and China had become the cornerstones of global shipbuilding, with their combined output dwarfing that of all other regions. South Korea emerged as the leader in constructing large and complex vessels—such as Very Large Crude Carriers (VLCCs), Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) carriers, and ultra-large container ships—through industrial giants like HD Hyundai, Samsung Heavy Industries, and Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering (now restructured as Hanwha Ocean). These firms leveraged cutting-edge technology, strong capital backing, and close government ties to capture global contracts.

Japan, though eclipsed by its neighbours in overall volume, maintained a strong reputation for quality and efficiency. Through established players such as Imabari Shipbuilding and Japan Marine United (JMU), the country specialized in building bulk carriers and high-quality, low-emission vessels. Japan’s shipbuilders relied on incremental innovation and operational excellence to remain competitive despite rising regional pressures.

China, meanwhile, was the most rapidly ascending force. With substantial support from the state, the China State Shipbuilding Corporation (CSSC) and other affiliated entities rapidly expanded capacity and scale. Through a blend of state ownership, vertical integration, and cost competitiveness, China positioned itself as a volume leader and, by 2022, had become the world’s largest shipbuilder by output. This rise reflected not only raw production capacity but also an increasingly sophisticated approach to maritime industrial policy.

2008 GFC - Collapse and Consolidation: The onset of the Global Financial Crisis in 2008 marked a period of unprecedented turbulence for global shipbuilding. As global trade volumes plummeted and commercial shipping routes faced historic contraction, demand for newbuild vessels collapsed. Orders for new ships declined by nearly 70 per cent between 2008 and 2010, leaving shipyards underutilised and financially strained. Numerous smaller yards closed altogether, while even major industry players faced insolvency risks and dramatic reductions in order volume, including the widespread cancelation of existing orders, leaving yards exposed to immense liabilities and unfinished projects strewn about.

South Korea responded swiftly and decisively. The Korean government, through the Korea Development Bank, provided targeted liquidity injections and credit support to major firms. The government also encouraged industry consolidation, culminating in the formation of Korea Shipbuilding & Offshore Engineering (KSOE) under HD Hyundai’s leadership. This allowed Korea to maintain its technological edge and survive the crisis with its core capabilities intact.

In their own efforts, the Japanese government introduced low-interest loans for shipbuilders and enhanced export credit guarantees to stimulate overseas demand. This support also facilitated the consolidation of industry players, including the merger that formed Japan Marine United (JMU). Though Japan’s global share continued to decline, its emphasis on quality and financial prudence allowed it to stabilize and protect key industry assets.

Beijing, on the other hand, facilitated the merger of its two largest shipbuilding conglomerates, CSSC and CSIC, creating a single national champion capable of scaling efficiently. Simultaneously,the Chinese government introduced value-added tax rebates, direct export credits, and substantial R&D funding focused on LNG, dual-fuel, and naval ship construction. These measures laid the groundwork for China’s eventual rise to global dominance in output volume.

COVID-19 - Disruption and Resilience: The COVID-19 pandemic, which emerged in 2020, brought a fresh wave of disruption to the global shipbuilding sector. Yards were forced to suspend operations due to lockdowns and safety regulations, leading to project delays and supply chain bottlenecks. The pandemic also caused labour shortages, surging steel prices, general uncertainty in the shipping market, and—once again—immense order cancellations.

Yet, by mid-2021, the market experienced an unexpected reversal. The explosion of global e-commerce, combined with supply chain reconfigurations and heightened demand for LNG infrastructure, drove a sharp rebound in newbuild orders. Europe’s efforts to reduce reliance on Russian gas, coupled with an emphasis on cleaner energy, spurred demand for LNG carriers and green-fuel-capable ships.

Governments in Korea, Japan, and China moved quickly to support their industries. Wage subsidies, tax deferrals, and infrastructure investment were rolled out across all three nations. South Korea specifically focused on high-tech dual-fuel ships, reinforcing its niche in LNG and clean propulsion. China prioritised capacity expansion for LNG and methanol-fuelled ships, aligning with its broader decarbonization goals. Japan leveraged its shipyards’ efficiency and environmental record to reposition itself in the low-emission vessel segment.

Green Transition and Mega Orders: The period from 2021 to 2024 marked a phase of aggressive resurgence for East Asia’s shipbuilders. South Korea secured over $45 billion in new orders for LNG carriers and ultra-large container vessels from major global clients such as QatarEnergy, Hapag-Lloyd, and Maersk. These orders were not only a testament to Korea’s engineering capabilities but also a direct result of state-supported innovation in dual-fuel propulsion and automation.

China’s CSSC capitalised on economies of scale and generous government support to dominate the mid- and low-cost vessel segments. It also made significant inroads in next-generation shipping, including dual-fuel and methanol-powered vessels, winning mass contracts from global shipping companies eager to comply with evolving emission standards.

Japan, while not matching its neighbours in order volume, leveraged its comparative advantage in environmental technology. Japanese yards carved a niche in low-emission vessels, ferries, and specialized ships, allowing them to retain relevance and financial viability in a competitive market.

The broader recovery was shaped by three strategic pivots: the adoption of green vessels (LNG and methanol), investments in automation and yard infrastructure, and the rising demand for offshore support vessels. These shifts redefined competitive advantage and created new growth pathways.

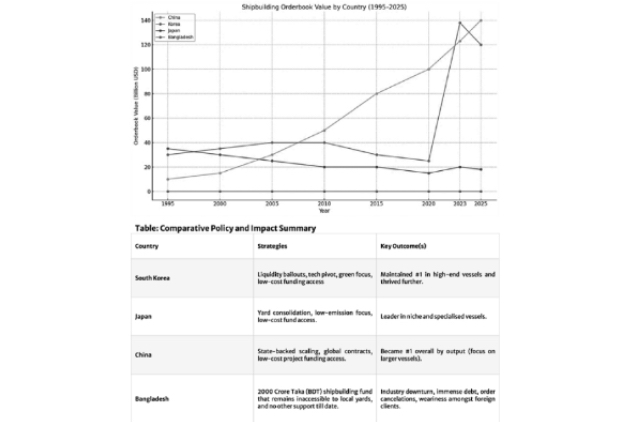

The graph below highlights the orderbook/production value of China, Japan, Korea, and Bangladesh’s shipbuilding industries, in the Billions of US Dollars. As is evident, Bangladesh’s orderbook value—relative to major shipbuilding players—remains negligible; a reality that can quickly be reversed, given the correct support.

Policy Recommendations for Bangladesh: The coordinated interventions seen in Korea, Japan, China, and many other shipbuilding dominant nations underscore the importance of government leadership in supporting a complex and capital-intensive industry like shipbuilding. For Bangladesh, which possesses the geographic and demographic advantages necessary to compete in the global maritime space, three primary areas of policy intervention stand out.

Strategic Financing Tools. Bangladesh Bank needs to introduce, and make accessible, a dedicated, long-term project financing facility for shipbuilding, offering preferential interest rates, sovereign guarantees, and export credit support. Access to low-cost infrastructure funding—akin to what was provided through state-backed banks in Korea and China—can provide domestic yards with the capital security needed to scale up, upgrade technology, and confidently pursue international contracts.

Industry Consolidation and Debt Restructuring. A rationalisation of the domestic shipbuilding landscape is necessary. Many smaller yards in Bangladesh operate below capacity or remain idle due to unresolved debt obligations. Government-led restructuring—potentially through debt forgiveness, bailouts, or strategic mergers—can create a leaner, more competitive industry base. This mirrors successful consolidation programs implemented in Japan and Korea during times of crisis.

Green Shipbuilding Incentives. As the global fleet pivots toward low- and zero-emission vessels, Bangladesh must align with future standards. Targeted subsidies for R&D, training in green fuel technologies, and support for international certification can help local yards transition toward building dual-fuel LNG, methanol, and hybrid ships. These policies will prepare the country to meet demand from global clients increasingly bound by regulatory emissions limits.

Unlike the mature shipbuilding economies of East Asia, Bangladesh faces no constraint in terms of available manpower. On the contrary, it possesses an abundant pool of skilled and semi-skilled workers. Notably, a majority of shipyard workers in Singapore—themselves builders of highly advanced ships—are of Bangladeshi origin. Shipbuilding remains one of the most labour-intensive manufacturing industries in the world. And, when labour is not a limiting factor, the possibilities for expansion and long-term growth become virtually boundless. This comparative advantage must be placed at the core of any policy strategy to revive and modernise Bangladesh’s shipbuilding sector.

Conclusion: The post-crisis resurgence of Korea, Japan, and China demonstrates how state intervention, modernisation, and strategic alignment with global market trends can transform a vulnerable industry into a national asset. Bangladesh, with its abundant labour pool and high optimised and favourable geography, holds untapped potential in shipbuilding. A coordinated, policy-driven approach—centred around financial incentives, capacity building, and export-oriented industrialisation—can lay the foundation for a competitive and resilient domestic shipbuilding sector.

Zahin Hasan is Graduate Finance Student, Bentley University, Massachusetts, USA. zahin.hasan16@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.