Published :

Updated :

It has become a standard refrain in the lexicon of international development institutions and local protagonists: Bangladesh suffers from an abysmally low tax-to-GDP ratio. At barely 7.5 per cent, it trails not only global averages but also regional peers such as Nepal, whose ratio hovers around 18 per cent. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, and many in the Bangladeshi policy community often argue that this deficiency undermines the country’s ability to mobilise resources for infrastructure, health, education, and other developmental priorities. The prescription offered is almost always the same: broaden the tax net, if not raise the tax rate.

While the argument has surface appeal, it is ultimately mechanical and narrow. It assumes that a low tax-to-GDP (Gross Domestic Product) ratio is inherently problematic and that simply raising it will unlock a development dividend. However, this perspective overlooks the deeper structural and moral dimensions of taxation, particularly in a country where corruption, inequality, and a lack of public trust in state institutions have eroded the social contract.

Corruption and the Moral Basis of Taxation: A crucial omission in the mainstream tax discourse is the role of corruption. Bangladesh routinely ranks near the bottom of Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), scoring 23 out of 100 in 2024, placing it 151st out of 180 countries. This level of systemic corruption erodes not only the efficiency of tax collection but also the moral foundation of taxation itself.

Why should citizens comply with taxation if they perceive their contributions as financing the high-living of government officials or disappearing into off-the-books accounts? The moral legitimacy of taxation rests on the belief that revenues will be used to fund public goods and social justice. In a country perceived to be a significant player in the global corruption league, this belief collapses.

Consider the recent revelations that a former Land Minister owned 360 luxury properties in the United Kingdom (UK) alone and around 100 additional properties globally, a staggering accumulation for someone with a modest official salary. This case, while extreme, reflects a broader pattern of similar ownership among senior officials, politicians, and their associates. Such illicit capital outflows not only deprive the state of needed resources but also set a damaging precedent. If the wealthy and powerful can offshore their incomes and assets with impunity, why should the ordinary taxpayer play by the rules?

Moreover, Bangladesh allows “voluntary disclosure” schemes, where individuals can repatriate illicit wealth with minimal tax penalties. These amnesties, while expedient for revenue, undermine long-term compliance and reinforce the perception that tax evasion is both low-risk and reversible. Additionally, there is no evidence that such tax forgiveness has yielded any significant revenue in the past.

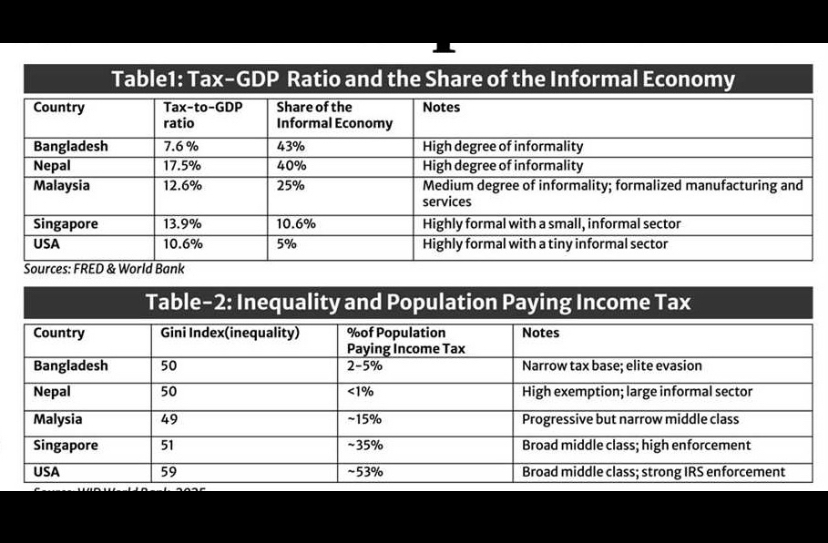

Structural Features of the Economy: Tax performance is not merely a function of administrative efficiency or enforcement capacity; it is deeply linked to the structure of the economy, particularly the size of the formal economy. Let us consider a few illustrative comparisons based on the latest available data. See Table-1, where the Tax-GDP data column in the table is drawn from FRED and the World Bank, while the column on the share of the informal economy is derived from the World Bank’s Informal Economy Database.

Other things remaining the same, the table suggests that informality is negatively correlated with the tax-GDP ratio. Consider Bangladesh, whose economy remains largely informal, with agriculture, microenterprises, and cash-based transactions dominating a vast segment of national output. In terms of informality, Bangladesh is somewhat comparable to Nepal, which, paradoxically, has a much higher tax-to-GDP ratio. We will try to explain the paradox later.

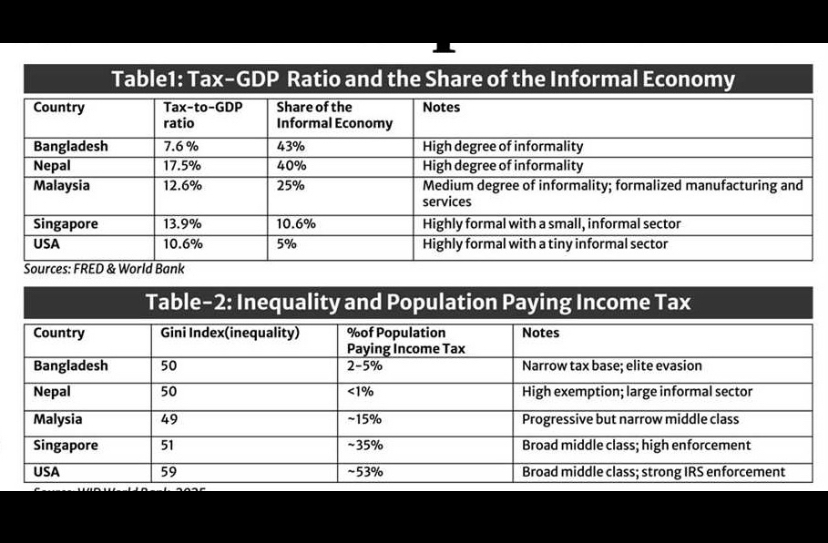

Income Distribution and Tax Compliance: Consider Table-2 below. Column 1 here presents the Gini data compiled from the World Bank’s World Inequality Database (WID) for 2025, while the data on the percentage of the population paying income taxes are sourced from various country reports. The latter data are more indicative than definitive. As the table shows, Bangladesh’s income tax base is exceptionally narrow. Out of a population exceeding 170 million, fewer than 2.5 million people filed income tax returns in FY 2021–22, which is less than 1.50 per cent of the population, and likely only 2–5 per cent of those with taxable incomes. This stark gap reflects both limited administrative reach and widespread evasion among high-income earners. Nepal fares no better: it has fewer than 1 per cent of its population paying personal income tax, due to agricultural exemptions and a vast informal economy.

Even in high-income countries, income distribution plays a critical role in shaping tax outcomes. For instance, in the United States—where the GDP per capita exceeds $80,000—around 47 per cent of households pay no federal income tax. This is not necessarily due to tax evasion but rather reflects the extent of inequality in society: a large portion of the population falls below the income threshold required to owe federal income tax (Tax Policy Center). In fact, many of these households receive an average of approximately $5,000 in income transfers from the federal government through programs such as the Earned Income Tax Credit, Child Tax Credit, and food assistance. This fact highlights the salience of examining tax participation in conjunction with income levels and the state’s redistributive role.

Notwithstanding their egregious inequality, high-income societies such as Singapore and the US have, however, a broader tax base anchored in a wider middle class. Income tax compliance is higher in the middle class not only because enforcement is stricter, but also because they have a vested interest in public services funded through taxes.

Although official data may understate the extent of this inequality, Bangladesh is a highly unequal society: Much of the nation’s wealth is concentrated in a narrow elite that enjoys numerous exemptions, incentives, and often, de facto immunity from enforcement. A large portion of the working population falls below the income tax threshold. Those who do qualify frequently find ways to underreport or obscure their income. The result is a system where the tax-paying middle class bears a disproportionate share, while the wealthy and powerful either evade taxes or shift their capital abroad.

These cross-country comparisons suggest that inequality and informality are closely linked to weak tax performance. Without reforms to make the system more equitable and inclusive, simply raising tax rates or expanding the tax base will likely be both ineffective and regressive.

The Nepal-Bangladesh paradox explained: A closer look at Nepal offers instructive insights. Despite having a smaller and less diversified economy, Nepal consistently outperforms Bangladesh in tax collection. Several factors contribute to this outcome. First, Nepal relies heavily on indirect taxes such as VAT, customs duties, and excise taxes—especially at border points—where compliance is easier to enforce. Bangladesh, in contrast, struggles with widespread underreporting and non-compliance with VAT.

Second, Nepal has benefited from greater reform momentum, driven in part by stronger donor oversight. Its 2015 shift to fiscal federalism also empowered local governments to collect property and service taxes, thereby broadening the tax base. In contrast, Bangladesh’s tax administration remains highly centralised under the National Board of Revenue, which limits local capacity and accountability.

Third, public trust in tax institutions is marginally stronger in Nepal, as reflected in its higher CPI score of 34 (100th globally) compared to Bangladesh’s 23 (151st). While corruption remains an issue in both countries, the perception that tax revenue is more likely to fund public services than private luxuries is more prevalent in Nepal.

Finally, Nepal’s excise tax regime is more effectively enforced. Taxes on fuel, alcohol, and telecommunications make a significant contribution to the country’s revenue. In contrast, excise taxes in Bangladesh are underutilised and often undermined by smuggling and under-invoicing.

In sum, Nepal’s relatively higher tax-to-GDP ratio is not simply the result of better administration but of systemic efforts to expand the base, decentralise collection, and build public trust—lessons that Bangladesh would do well to heed.

Lessons and the Way Forward: The incentive to pay taxes is closely tied to the quality and transparency of government expenditures. When citizens perceive that their tax money is used prudently—for infrastructure, education, or health—they are more inclined to comply. Conversely, ostentatious and wasteful public spending undermines tax morale. In Bangladesh, the spectacle of long motorcades for ministers and high-ranking officials, as well as the use of luxury government vehicles and overseas medical treatments at public expense, stands in sharp contrast to the lives of ordinary citizens. Having had the opportunity to live in capital cities such as Washington, DC, Tokyo, Singapore, and Manila for an extended period, I have never witnessed the kind of official extravagance that is so commonplace in Dhaka. This disparity not only erodes public trust but sends a message that governance serves privilege, not the public good.

Another critical area of reform lies in addressing the skewed distribution of income and the lavish, often unaccountable, expenditure of the state’s upper echelons. The government must take visible steps to curb excessive spending by public officials, parliament members, and military elites. When state representatives live in stark contrast to the people they govern, enjoying perks, vehicles, and foreign medical care at taxpayers’ expense, it breeds resentment and weakens the moral contract that underpins tax compliance. Instituting strict budgetary discipline, transparent audits, and caps on official privileges can help restore a sense of fairness and legitimacy to public finance.

The lesson from these comparisons is clear: raising the tax-to-GDP ratio is not just a matter of better administration or wider nets. It requires building a tax system that is legitimate, equitable, and rooted in social trust.

For Bangladesh, this means the following:

- Fighting Corruption. A credible anti-corruption drive is indispensable. But beyond symbolic gestures, anti-corruption efforts must focus on recovering lost revenues from systemic evasion by powerful business interests. Holding unscrupulous businesspeople accountable for unpaid taxes and illicit wealth transfers could yield a substantial fiscal dividend, potentially more significant than what could be gained by broadening the tax base among low-income earners. Targeted audits, forensic investigations, and enforcement of tax laws on high-net-worth individuals and politically connected firms should be top priorities.

- Broadening the Formal Economy. Encouraging formalisation through digital payments, simplified registration, and incentives for SMEs can expand the tax base. Policymakers might consider Vietnam’s experience, which has made notable progress in formalizing its SME sector over the past two decades, beginning with the 2005 Enterprise Law. This progress was achieved through a combination of legal reforms, administrative simplification, financial incentives, and the use of digital tools.

- Reforming Tax Expenditures. Rationalising exemptions and incentives that benefit the wealthy disproportionately. Consider replacing blanket corporate incentives with performance-linked tax credits tied to job creation or export diversification. Review and gradually phase out ineffective tax holidays for special economic zones.

- Improving Public Spending. Tax compliance will only improve when citizens see visible benefits from their contributions, such as clean water, reliable roads, and quality schools. Consider implementing pilot participatory budgeting in municipalities, enabling citizens to help prioritize local spending on schools, roads, and clinics, as pioneered in Brazil. Additionally, the government might consider launching infrastructure tracking dashboards that show the real-time progress of public projects funded by tax revenue, similar to India’s Gati Shakti portal. Scaling back or canceling mega projects and redirecting funds to health and education could also be beneficial.

- Enhancing Transparency. Publish regular tax data, enforcement outcomes, and the use of revenue in public dashboards. Establish an open-access public finance portal that displays tax collections by sector and budget allocations by the ministry, modeled on the US government’s “USAspending.gov.” Establish a public grievance redressal mechanism that allows citizens to report harassment or corruption anonymously, with mandatory follow-up and accountability measures in place.

Conclusion: Bangladesh’s low tax-to-GDP ratio is not the disease—it is a symptom of a deeper malaise. Fixating on this metric without addressing the underlying rot of corruption, elite capture, inequality, and institutional mistrust will lead nowhere. Taxation is not simply a technical policy instrument—it is a moral contract between citizen and state. And right now, that contract is broken.

What Bangladesh needs is not another donor-mandated revenue target, but a comprehensive political and institutional overhaul that restores public confidence, expands the formal economy, and ensures that taxation serves the many, not just the privileged few. Until that happens, the tax-GDP debate will continue to be a distraction from the country’s real problem: a state that taxes without trust and spends without accountability.

Dr MG Quibria is a development economist and former Senior Advisor at the Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI). He holds a Ph.D. in economics from Princeton University and has held academic appointments across Asia,

North America, and Europe. mgquibria.morgan@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.