Published :

Updated :

Imagine this: your lights never flicker, your industrial machinery runs without interruption, and voltage stays perfectly within safe limits. If you care about climate, you can choose to source more of your electricity from renewable energy. Your utility predicts demand accurately, plans its investments sensibly, and ensures electricity remains affordable. Would you pay a little more?

This vision is not a distant fantasy. In countries across Europe, North America, and increasingly in Asia, smart grids-grids that are digitally managed, automated, and adaptive-are making such reliability a standard feature, not a luxury. In India’s industrial hubs and Vietnam’s growing manufacturing zones, grid stability is no longer seen as an engineering challenge alone, but as a prerequisite for economic competitiveness.

What is a Smart Grid?

A Smart Grid is an electricity network enhanced with digital technology to allow two-way flows of both electricity and information. It continuously monitors its own performance, detects faults, and makes adjustments to ensure power quality and reliability. In practical terms, this means fewer and shorter outages, better voltage and frequency control, and more flexibility to integrate renewable power sources like solar and wind.

In the traditional model, electricity flows in one direction-from power plants to transmission lines, to distribution networks, and finally to consumers. Operators have limited visibility of what is happening at any point in the system, and response to faults often relies on manual checks and phone calls.

Reliability and Power Quality

To appreciate the value of smart grids, we can start with some basics from high school physics. Electrical power systems in Bangladesh are designed to operate at a frequency of 50 hertz (Hz). This means the alternating current reverses direction 50 times per second. Frequency stability is essential because many devices and industrial processes depend on a constant speed of electrical cycles.

Two measures-System Average Interruption Frequency Index (SAIFI) and System Average Interruption Duration Index (SAIDI)-ensure reliability from the consumer’s perspective. SAIFI records how often, on average, a customer experiences a power outage in a year. SAIDI measures the total duration of those outages. Low SAIFI and SAIDI values are the hallmark of a reliable grid.

Voltage control is equally critical. Voltage can be thought of as the pressure in the electrical system, pushing current through wires and into devices. Too high a voltage can damage sensitive equipment; too low a voltage can cause motors to run inefficiently or stall. Voltage fluctuations also accelerate wear and tear on machinery, leading to higher maintenance costs.

The health of an economy’s industrial base is tied to these technical details. Inconsistent power quality slows production, reduces output, and can deter foreign investors who rely on guaranteed uptime.

Technologies that Enable Smart Grids

Smart Grids are built on a foundation of integrated technologies. The Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) system is the operational nerve centre, allowing utilities to monitor and control substations, feeders, and other assets in real time. SCADA systems collect and display data from sensors, giving operators the ability to respond quickly to faults.

The Advanced Distribution Management System (ADMS) adds intelligence to SCADA. It automates network switching, optimises power flows, and integrates outage management. An Outage Management System (OMS) identifies the exact location of a fault and helps dispatch crews more effectively.

Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI) is another key piece. Smart meters measure electricity consumption in real time and send this data back to the utility automatically. This enables accurate billing, faster detection of outages, and demand management programmes that encourage consumers to shift usage away from peak times.

Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) store surplus electricity during low-demand periods and release it when demand peaks. This smoothens out fluctuations, supports frequency control, and enables greater use of intermittent renewable energy.

Bangladesh’s Progress So Far

Several initiatives are underway, though most remain limited in scope. Dhaka Power Distribution Company (DPDC) has begun a smart grid pilot with funding support from the European Union and implementation by AFD, focusing on automation and power quality improvement. Northern Electricity Supply Company (NESCO) is implementing SCADA, OMS, GIS, and a substantial smart meter rollout

In the west, the West Zone Power Distribution Company (WZPDCL) has deployed automation projects, while the Bangladesh Rural Electrification Board (BREB) is rolling out hundreds of thousands of smart meters. These are promising steps, but they are fragmented. Without integration, common data standards, and sector-wide capacity building, these projects cannot deliver the full benefits of a Smart Grid.

Financing and Incentives

Smart Grid deployment demands substantial capital investment. Experience from other countries shows that well-planned projects can recover costs through operational savings and efficiency gains within five to seven years. Yet in Bangladesh, the regulatory framework often undermines incentives for utilities. Efficiency improvements can lead to tariff adjustments that erase any financial gains, discouraging investment in modernisation.

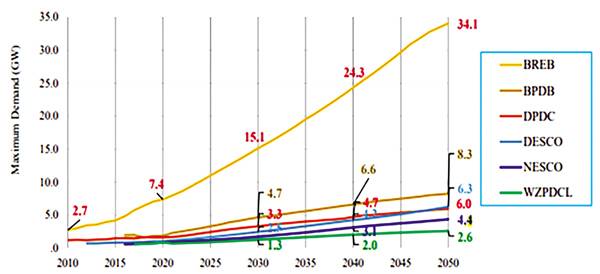

Picture: Bangladesh Energy Curve, retrieved on 8 August 2025

Reforming tariff structures to reward performance, allowing differentiated service levels, and creating market mechanisms for ancillary services-such as frequency control provided by batteries-can attract both domestic and foreign capital. Public-private partnerships could finance elements like EV charging infrastructure and large-scale battery storage.

Lessons from Regional Peers

India has made significant progress in integrating renewable energy into its grid, using wide-area monitoring systems and automated generation control to manage variability. Vietnam has expanded transmission capacity and invested in storage to smoothen out solar generation spikes. Malaysia is upgrading its grid to attract data centre investments, viewing power quality as a cornerstone of its digital economy ambitions.

These examples highlight a critical point: grid modernisation is not just about engineering-it is an economic strategy. Countries that invest in reliable, high-quality electricity supply position themselves to capture the industries of the future.

The Case for Smart Grids: Why is it NOW and not in FUTURE

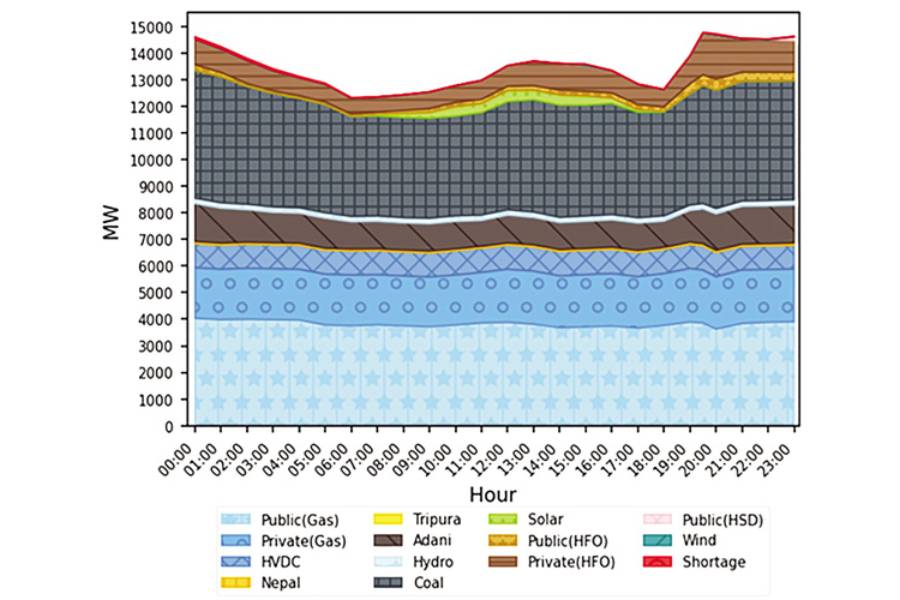

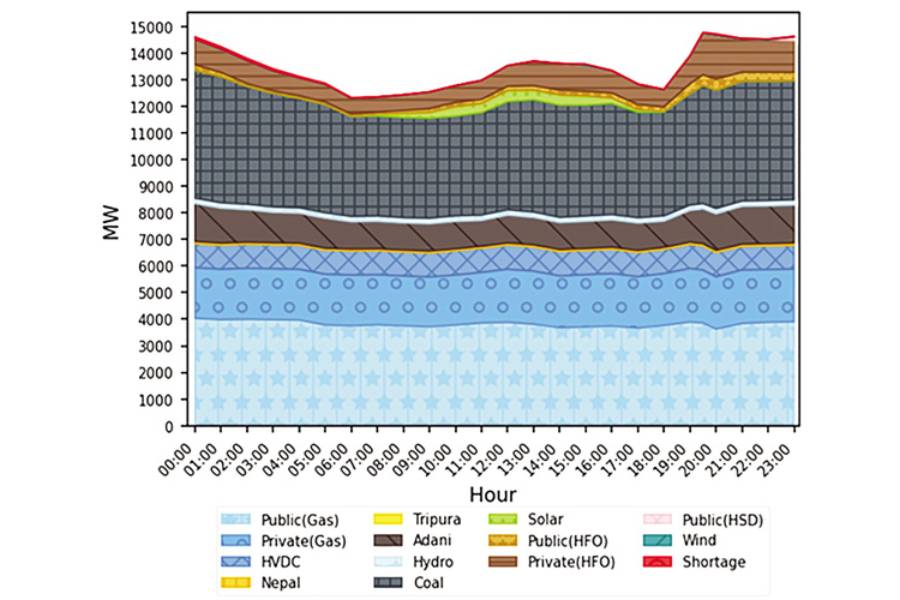

If you look at the chart below, it illustrates how Bangladesh’s power system draws from a complex mix of fuel and supply sources-domestic gas, imported power via HVDC links, coal, hydro, solar, heavy fuel oil, and cross-border contracts with Tripura and Adani-while managing shortfalls at peak times. Balancing these diverse inputs is a constant operational challenge, with each source carrying different costs, ramping capabilities, and reliability profiles. A smart grid, with advanced forecasting, real-time monitoring, and control can really keep the costs down.

The case for Smart Grids in Bangladesh is also urgent on the distribution side, because of the volume of power the utilities are having to handle. According to utility-wise demand handling of power in IEPMP 2022, Bangladesh has a different hallmark. It is dominated by small consumers, in geographically diverse settings.

The future economy will be driven by sectors that demand uninterrupted, high-quality power: advanced manufacturing, semiconductor fabrication, artificial intelligence data centres, and high-end services. Regional competitors are already upgrading their grids to meet these requirements. Bangladesh must act quickly to remain competitive.

Major blackouts in 2014 and 2022 demonstrated the vulnerability of the current system. Without fast detection and response capabilities, small faults cascaded into nationwide outages. Every such event imposes a hidden tax on the economy in the form of lost production, damaged equipment, and reduced investor confidence.

The choice is clear: continue with incremental upgrades and risk falling further behind, or commit to a coordinated, sector-wide modernisation that makes reliability and quality the standard, not the exception. The Government should form a separate working council akin to SREDA for promotion of Smart Grids. Institutional reforms must happen at the distribution company level.

Every flicker of a lightbulb, every hum of an overloaded motor, every shutdown of a production line is a signal that Bangladesh’s power infrastructure is not yet ready for the demand of the future. It is smarter to invest openly in a grid that delivers stability than to keep paying the hidden costs of one that does not.

The writer is a Partner and Director at a Dhaka-based consulting firm, Inspira Advisory and Consulting Limited.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.