Published :

Updated :

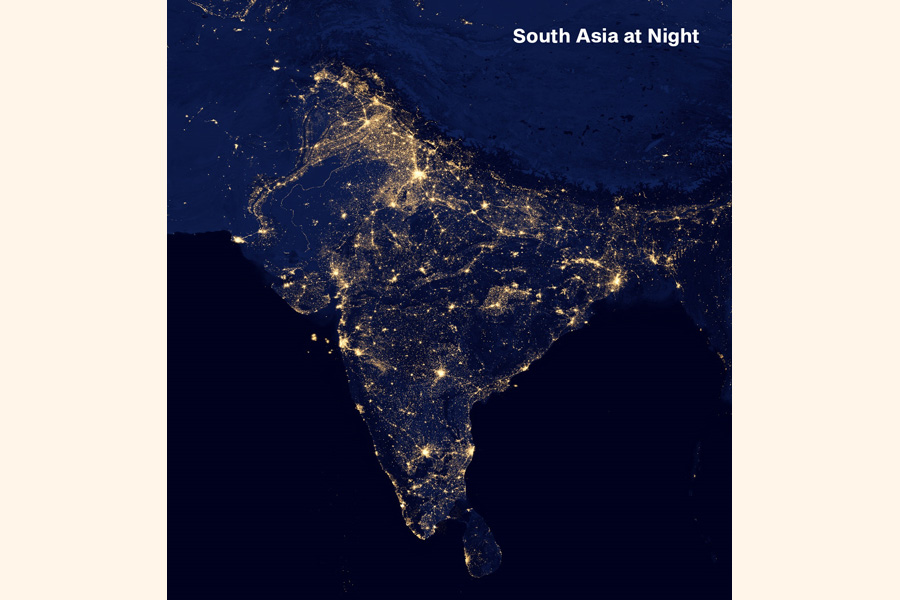

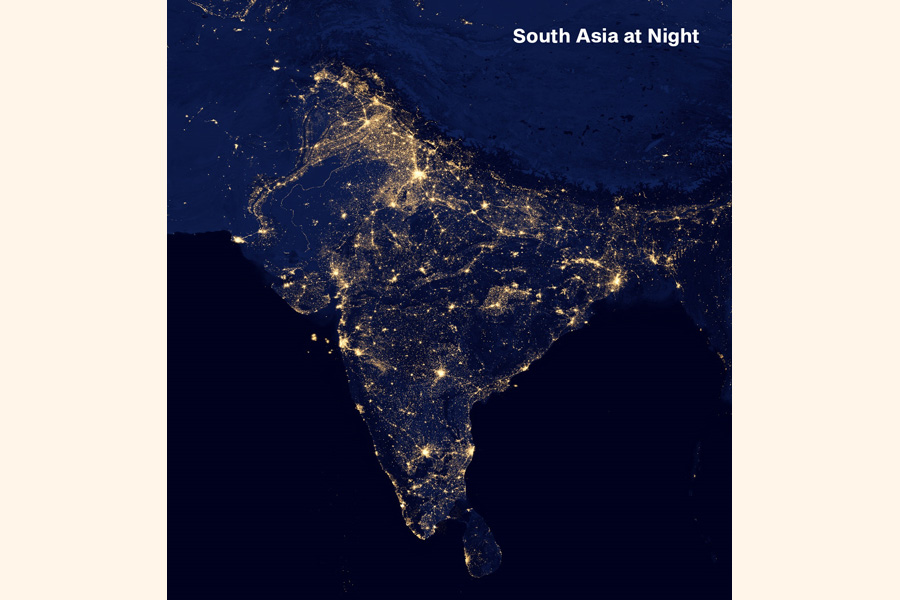

Recently in a discussion with some fellow researchers about the notion of nighttime lights as a proxy for economic activity, I was reminded that many Bangladeshi scholars remain sceptical of this approach. They argue that, apart from big cities like Dhaka, Chittagong, and Gazipur, not much happens at night in most of Bangladesh. They say nighttime lights might work in Africa, where data is limited, but Bangladesh has comparatively better data, making satellite measures less useful. Their main point is that since there's little economic activity at night, it's unclear whether nighttime lights are a reliable measure of the economy.

This scepticism is understandable, but it overlooks strong evidence from economic research that questions these assumptions. The basic idea behind using nighttime lights to track economic activity is that modern economic activity at night usually involves artificial lighting, which satellites can detect across entire countries. When people work, shop, or do business at night, they tend to use lights that satellites can often detect. More activity usually means more lighting, and satellites capture this pattern consistently, though very small or indoor lights may not always be visible.

The scepticism about using nighttime lights in Bangladesh might come from the fact that in rural areas, lights are mainly used for consumption and not necessarily for production or economic activities. For instance, outside major urban centres, most nighttime lighting tends to serve household needs-cooking, studying, socialising-rather than manufacturing or commercial production. This leads to the conclusion that nighttime lights reflect consumption patterns more than actual economic output, making them a poor proxy for economic activity.

This view of consumption versus production, however, misses an important point about what counts as valuable economic information. Rural consumption patterns actually reveal important information about economic health and development. Households can only afford to use electricity for lighting if their income and economic situation allow it. Just as a family's grocery spending conveys economically meaningful information, when rural areas have more nighttime lighting, it signals higher income, better living conditions, and confidence to spend on electricity. This consumption shows real economic progress, even if the production behind it happens somewhere else or during the day.

Importantly, consumption can also point to future economic potential. When households spend on lighting for evening study, they're investing in skills that can boost growth later on. When rural businesses use electric lights to work longer hours, they can take advantage of more economic opportunities. These lighting choices show both how much people can afford now and their hopes for the future, making nighttime lights a useful way to predict economic growth.

Also, the line between consumption and production is not so clear in rural areas. Rural lighting often supports evening markets, farm processing, home businesses, and service centres that work after dark, though the full extent isn't fully known. Even when lights are mostly used for household needs, this use often shows income from farming, money sent by migrant workers, or rural businesses outside farming. Lighting helps people learn in the evening and lets small businesses work longer hours.

The connection between electricity access and nighttime lights adds another view to this debate. While most nighttime lights need power, that power can come from the national grid, solar energy, or other sources. In remote areas of Bangladesh, like the chars (river islands), solar power has greatly boosted economic activity even without grid electricity. A recent study by Friendship in Kabilpur Char, Gaibandha, shows that solar power helped shops stay open longer, medicine stores keep refrigerators running, and women work at night on income activities like sewing and tailoring.

This difference matters for policy. Bangladesh has made great progress in bringing electricity to rural areas, but the important question isn't just if villages have electricity-it's whether they are using it in ways that help the economy grow. Nighttime lights capture this economic dynamism in ways that basic infrastructure data can't. They reveal where electricity is being used for real economic work, not just where it's available.

The relationship between power access and nighttime lights also clarifies an important logical point about economic indicators. Nighttime lights need some form of power to show up, but having power access doesn't always mean there's real economic activity. This makes nighttime lights a cautious measure that ignores unused power infrastructure and shows where people and businesses actually use energy to work. It reflects behaviour, showing economic intent and activity-not just the presence of infrastructure.

For a country like Bangladesh, pursuing rapid economic development while keeping an eye on regional differences, nighttime lights have many practical benefits. The data is available globally, updated frequently, and gives consistent information about both cities and rural areas without being affected by different survey methods. Traditional economic surveys cost a lot, take time, and often miss informal work that's important in developing countries. Satellite data picks up these activities continuously and without bias.

I won't go into the large body of research supporting nighttime lights as a reliable economic indicator in developing countries-from studies showing strong correlations in rural Colombian municipalities with fewer than 5,000 people, to research across rural Africa linking light intensity with household wealth, education, and health, to evidence from low-density regions showing a clear relationship between nighttime lights and economic activity. Nor will I dwell on Bangladesh's well-known data limitations, especially at the sub-national level, which the World Bank has highlighted. These gaps don't weaken the case for using nighttime lights-they strengthen it. Satellite data provides consistent, frequent updates that help fill in where traditional statistics fall short.

As Bangladesh grows and tries to better understand its diverse regions, using tools like nighttime lights isn't just smart-it's necessary. These lights aren't perfect. They can't tell a wedding from a night market, or capture activity inside buildings or during power cuts. Rural patterns are harder to read, and seasonal changes can cause confusion. But these limits don't make the data useless-they just mean it should be used alongside other tools. The key question isn't whether nighttime lights show everything, but whether they reveal things we couldn't see otherwise. In a fast-changing country with limited data, even imperfect light can help us see what matters.

Syed Abul Basher is an economist and researcher.

syed.basher@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.