Biogas and Biomass: Fuelling a cleaner, greener future in rural Bangladesh

NAYMA AKTHER JAHAN and SHAHANA AFROSE CHOWDHURY

Published :

Updated :

A beneficiary with a biogas plant (Source: Impact Evaluation of Community-Based Innovative Rural Socio-Economic Development Programs of Kazi Shahid Foundation in Panchagarh District)

Bangladesh is faced with two closely-related rural challenges: the growing demand for domestic energy and the growing load of organic waste. For a country as agriculturally dependent as Bangladesh and still economically struggling with rural poverty, the possibility of generating energy from waste isn't just green-it also entails social and economic transformation.

Maybe the most convincing proof of such a change comes from the northern district of Panchagarh, where the Kazi Shahid Foundation (KSF) has led a model which links biogas production to rural entrepreneurship by women, organic agriculture, and environment-friendly development.

The Untapped Potential of Biogas

Biogas, produced from agriculture waste, domestic waste, and crop residues, has been hailed for decades as inexpensive, decentralized rural power. The potential has been held back by high upfront costs, maintenance problems, and poor public awareness.

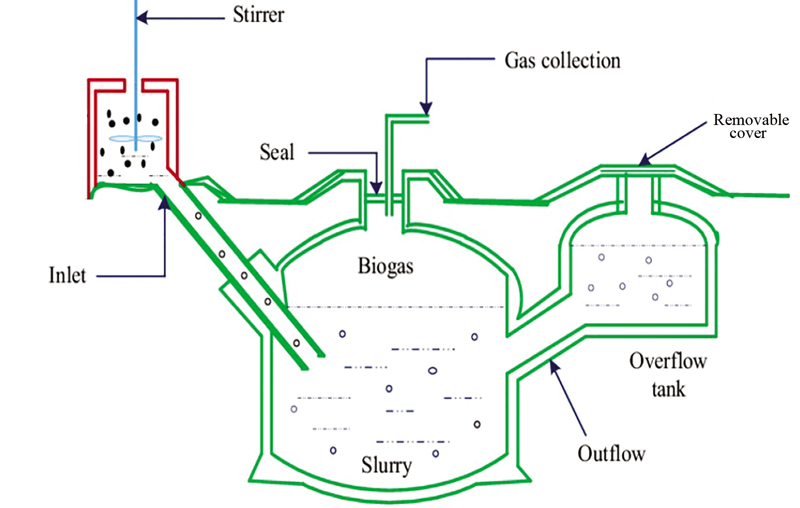

Kazi Shahid Foundation (KSF)'s Biogas Program responds directly to these issues. Originally launched more than a decade ago in partnership with the University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh (ULAB), the first brick-layered biogas plants were not durable and had maintenance issues. Aware of this, KSF re-launched the programme in 2015 and signed a Partner Organization agreement with Infrastructure Development Company Limited (IDCOL) to launch a new generation of portable fiberglass biogas plants.

These new systems are more energy-efficient, less prone to leakage, and easy to maintain. The biogas produced serves cooking and lighting needs, with the bio-slurry by-product being used as organic fertilizer, keeping chemical input costs extremely low and soil fertility high. Importantly, the scheme uses a non-traditional barter-based repayment method in which loans are repaid not in cash but in milk, dung, and slurry-lowering barriers to entry for poor households.

The KSF Biogas Model: A Rural Success Story

The Kazi Shahid Foundation (KSF) model is not just about energy; it's about empowerment and ecosystem restoration. Women in Panchagarh, previously without any source of income, now run their own micro-dairies, supply organic fertiliser to tea gardens, and reduce the use of wood fuel and kerosene.

Mean family income per year for biogas and dairy beneficiaries doubled from Tk 214,000 (non-KSF) to Tk 472,000 (KSF members), thanks to KSF's impact assessment (2018). Dairy income increased alone from Tk 38,000 to Tk 177,000 per household. This was supplemented by the enhancement of resilience to shocks, more school children remaining in school, and a reduction in cases of domestic violence.

Under the model 6,750 cattle were distributed among members and an integrated system was created that cycles waste back into energy and fertiliser. The outputs are in turn cycled back into agriculture and markets-facilitating a circular rural economy.

Biomass: Power from Agricultural Waste

While biogas powers homes, biomass energy --- from rice husk, jute sticks, sugarcane bagasse, and other agricultural waste -- can power rural enterprises. Bangladesh generates enormous quantities of such waste, much of which is inefficiently burnt or simply lost.

With suitable investment, biomass mini-grids or gasifier technology could power rice mills, rural SMEs, and even off-grid villages. The potential is especially large in regions like Rangpur, Rajshahi, and Barishal where agro-industry is growing.

Yet biomass confronts the same difficulties: scant policy incentives, lack of financing systems, and a dearth of technical capacity at the local level. Rural modernisation of biomass may not only contain deforestation and emissions, but also productivity in agro-industries.

Barriers and Bottlenecks

Absence of financing

Rural residents do not have financial resources or possessions that can be leveraged with banks as collateral to access loans. Banks are also not willing to lend biogas or biomass schemes unless the government guarantees or subsidises them. This makes it challenging for households or farmers to invest in such systems.

Missing policies

Bangladesh does not have a specific, separate national policy on bioenergy yet. The government agency responsible for renewable energy, SREDA, has not come up with a special plan to boost biogas and biomass growth. Without effective policy support, it is hard to establish this sector on a large scale.

Lack of technical know-how and support

Most of the current biogas and biomass infrastructure is also in a poor condition. This is especially because there are not enough trained technicians or qualified maintenance assistance in the rural areas. Without proper skills and services, these facilities quickly break down.

Low public awareness

Most rural communities remain ignorant of the benefits of biogas and biomass or even of utilizing these systems. Misinformation or fear of new technology in certain cases also discourages people from using it.

Way Forward: What Needs to Happen

For the maximum potential of Bangladesh's bioenergy to be achieved, policymakers, funders, and development partners must collaborate in concert. They have certain recommendations, which are:

- National Bioenergy Roadmap: SREDA must develop a special plan for biogas and biomass by 2026, mapping feed stocks, technology options, and investment pipelines.

- Green Financing for Cooperatives: Similar models like KSF's barter repayment mode can be replicated with the support of green funds and blended finance programs. IDCOL's ongoing support must be extended to biomass systems.

- Public-Private-Waste Partnerships: Urban organic waste-city market waste, slaughterhouse waste, and vegetable hub waste-can be diverted into rural energy ventures. Municipal governments must be urged to join hands with private energy firms.

- Invest in Innovation and Skills: R&D done at the universities and vocational training in bioenergy technologies can lead to localisation and create jobs. The BUET, BAU, and ULAB should lead the way in this.

Circular, Sustainable, Scalable

The KSF biogas model is unique in that it is integrated: cows provide dung, which produces gas and fertilizer, which enhances organic farming and tea cultivation, which in turn supports rural incomes. The model is cyclical, gender-sensitive, and scalable.

As Bangladesh transitions to cleaner energy and more inclusive development, bioenergy presents a singular chance to energize rural change from the grassroots. It is time to see models such as KSF not only as charity programmes, but also as scalable rural green economy interventions that align with the nation's climate ambitions and poverty reduction goals.

Nayma Akther Jahan is a Lecturer and Dr. Shahana Afrose Chowdhury is an Associate Professor at the Centre for sustainable Development at the University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh.

shahana.chowdhury@ulab.edu.bd, nayma.akther@ulab.edu.bd

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.