Published :

Updated :

One of the earliest use of the term North America was the British North American Act of 1854. Its immediate consequence was to produce the Canadian Confederation in 1867, whose 150th anniversary reminds us of another similar anniversary related to North America: the 'Seward Folly' of purchasing what was then called an 'icebox', that is, Alaska, by the United States from Russia. Quite a coincidence, too, that these two future superpowers actually invaded the each other's territory due to deliberate 1917 and 2017 actions. The 1917 Bolshevik Revolution actually involved US soldiers, as part of a foreign legion, fighting on behalf of the White Army, in Far East Russia, against Leon Trotsky's Red Army, a feat barely considered when so many missiles targeted each Cold War combatants from the other side between 1947 and 1987. And in 2017, Russian hackers having allegedly penetrated the 2016 presidential candidates' Internet accounts, lay the groundwork of not only a possible US presidential impeachment, but also a conceivably more lethal soft-power invasion than the missile-based Cold War could have wrought.

It is not by chance, then, to argue the North American idea has come full circle. The year 2017 marks the first year in which the formalised North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which gave the North American idea maximum exposure, mileage, and institutionalisation, is being negotiated for dismantling purposes, or at least being rewritten along nationalistic lines. Even the United States, after attaining all its mainland boundaries with the 1867 Alaska purchase, is also witnessing the largest out-migration to Canada, since the 1960s Vietnam War.

Clearly how imperilled the 'North America' idea had become had to wait so long to be fully understood. Even 36 years after US independence, both Great Britain and the United States were back at war. Though Washington, DC became a 1812 battlefront, slow and sputtered subsequent compromises even clashed when Great Britain openly supported the Confederates in the early 1860s Civil War, which the United States retaliated by not preventing Irish Fenians from invading Canada, between 1866 and 1871. Not until the 1941 Atlantic Charter brought the United States and its previous master together did the two countries resign to long-term peace and friendship. This is not to belittle the 'special relationship' that was brewing between the two countries from the end of the 19th Century. Yet, animosities openly remained as for each to directly target the other over tariffs in the 1930s - Great Britain through the 1931 Imperial Preferences, the United States through the 1932 Hawley-Smoot Tariff Act. Even in the Bretton Woods conference during the early 1940s, John Maynard Keynes and Harry Dexter White bickered with each other's positions. In fact, the two institutions that came out of those negotiations, the International Monetary Fund and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (World Bank), conformed to US intentions, not British. By the end of World War II, the more ferocious Cold War contestation brought them back together.

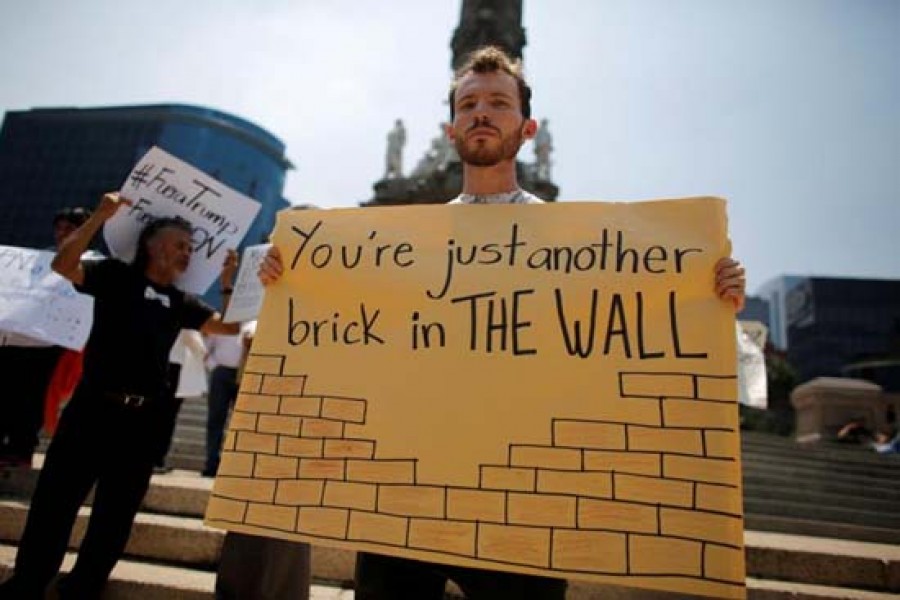

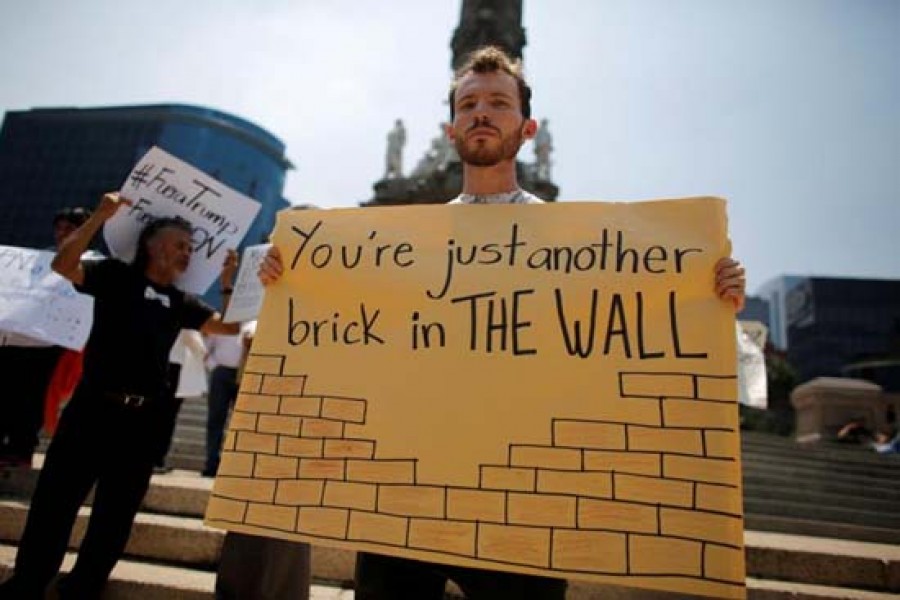

Canada-US relations did not gel until much, much later. Both were North Atlantic treaty Organisation (NATO) partners and Canada decidedly abandoned British positions to favour US counterparts incrementally after the 1930s, especially over trade. Yet, it was not until after Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, whose Third Option sought a US alternative, especially when the United States wanted to remain the only or most dominant Canadian option during the Cold War. Brian Mulroney began the negotiations in 1986 that culminated in the Canadian-US Free Trade Agreement (CUFTA) in 1988, eventually becoming NAFTA in 1993 and almost the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) in 2003. Although NAFTA results were impressive (inter-regional trade expanded, so much so that a billion dollar worth of goods/merchandise cross both Canada-US and Mexico-US borders every day), in many arenas, 'North American' identities and institutions actually ingrained themselves. What looked like a permanent development can come apart slowly but steadily: Mexican emigration supposedly eroded the North American gains made, while Mexican bilateral surpluses almost pushed the two countries to rupturing trade. Donald J. Trump alone smashed these southern 'North American' bonds by, first, stridently calling for NAFTA negotiations, then raising border-wall claims everywhere, and finally, by even labelling Mexicans as rapists and thieves.

Russia's North American interests ended with the Alaskan sale, and even the westward US movement targeting the Pacific was more interested in southern Asian contacts than northern Russian. Only with the advent of nuclear weapons from the late 1940s did 'North America' again enter Soviet/Russian calculations. Even that had a Canadian component: any missile from the Soviet Union targeting the United States would more likely be intercepted over Canadian territory than not. Much like NAFTA flows also generated a three-tiered engagement the three countries got less and less interested in, so too the three-tiered nuclear fallout possibility during the Cold War, since Canada fell between the two nuclear-armed countries. Although the Soviet breakdown did not fully entwine Russia and the United States, since nuclear missiles were still targeting each other, with the United States remaining the only superpower and not fully keen to redirect its nuclear missiles from Russia, Russia has turned to soft power, that is, media manipulation, to re-engage the United States again, that too during a very sensitive 2016 presidential election. At worst, the Russians interfered to peddle with US votes by breaking into Democrat Party sites, at best, the US president still remains one of the biggest Russian rooters within the United States, even as Vladimir Putin seeks more to reduce the gap between the United States and Russia than equanimity (or strategic parity).

As 2017 ended, then, 'North America' looked more fragile as a coherent identity than ever before, even as trade between its three members may be close to sky-high levels. Canada keeps only a formal linkage, much as Pierre Trudeau had done more than four decades ago, Mexico feels insulted by NAFTA progress being correlated to immigration and border-walls, and Russia salivating now that it has infiltrated US society more meaningfully than ever before. Domestic politics may have as much to do with these outcomes as public perceptions, but however we ascertain them, the hope-filled idea of a 'North America' region not only imploded very uncharacteristically, but also spewed so many more global implications.

First, it symbolises the clipped relative power of the United States; and whether its insulation is by choice or circumstances, clearly the end of the 'North American' era elevates other actors elsewhere. Second, the United States also seems to be implicitly abandoning the Monroe Doctrine by retreating to its own shell rather than the broader Western Hemispheric 'American' shell. Third, externally socialising Canada and Mexico may have more to gain relatively than the United States, and much more is predicted to be abroad than regionally. Fourth, the end of the 'North American' idea means a return to square-one: nationalism determining outcomes more than regional or global. Left alone, this transition can work its own way out without irrevocably shifting the status quo; but any state-driven measure too far carries the distinct possibility of long-term damage. The 'North America' idea might have symbolised only the region's relatively innocent moments.

Dr. Imtiaz A. Hussain is Professor & Head of the newly-built Department of Global Studies & Governance at Independent University, Bangladesh.

imtiaz.hussain@iub.edu.bd

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.