Published :

Updated :

Usually when the Boro harvesting season ends, landless and marginal farmers do not have much work in their villages for a few months. Before the COVID-19 pandemic struck the country, the coping mechanism they used was travelling to cities to find temporary work to support their families during the "lean" season. But for consecutive years now, they are seeing a fall in this temporary income solution due to travel restrictions, fear of infection and lockdown. Besides, finding temporary work in the cities became difficult.

Scarcity of work coupled with high food prices this year means that farm households are being forced to miss meals which result in reduced diet diversity and diet quality-- a shocking scenario for pregnant women and young children's nutritional needs.

Farmers are also having to deal with ever increasing natural calamities like frequent floods every year which destroy their crops. In the northern districts, farmers have suffered severe losses due to floods in the last three consecutive seasons. Due to joblessness and loss of crops, poor and marginal farmers are seeking financial support more than ever during the pandemic. To make-up the losses and meet household expenditure, the affected farmers usually seek loans from the local Mahajans (informal money lenders) and different non-government organisations (NGOs).

Farmers borrow money from informal money lenders at exorbitantly high interest rates. If a farmer borrows Tk 10,000, he must pay Tk 1,000 as monthly interest, so the interest rate is 120 per cent per annum. Under the 'haatra' system, a borrower of Tk 1,000 pays Tk 160 as interest in every haat day, which is the weekly market day. The yearly interest rate is 832 per cent in this case. Besides, Tk 100 installment is fixed upon the borrower against a loan of Tk 1,000 on 'current interest' (yearly interest rate of 3650 per cent!). Farmers usually end up paying a lot more as interest payment than the principal amount originally borrowed under these schemes.

Computing interest rates may seem irrelevant for these schemes, but we are doing this to compare with borrowing from formal banking institutions, which is set at only 4 per cent for agricultural loans during this pandemic. So, the obvious question is: why farmers tend to borrow from the informal sources rather than from formal banks? The simple answer is-- farmers borrowing money from the informal lenders think that process of borrowing from formal banks are complicated.

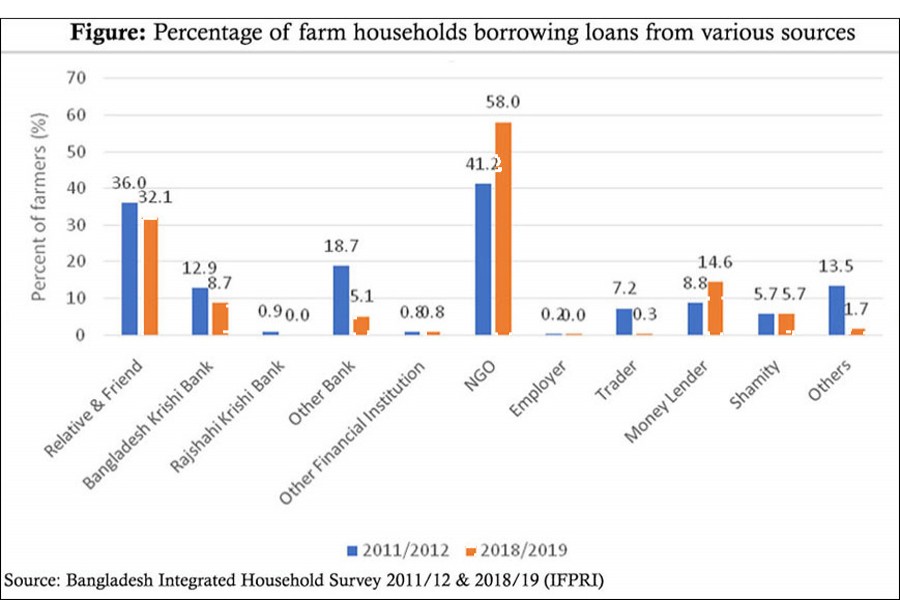

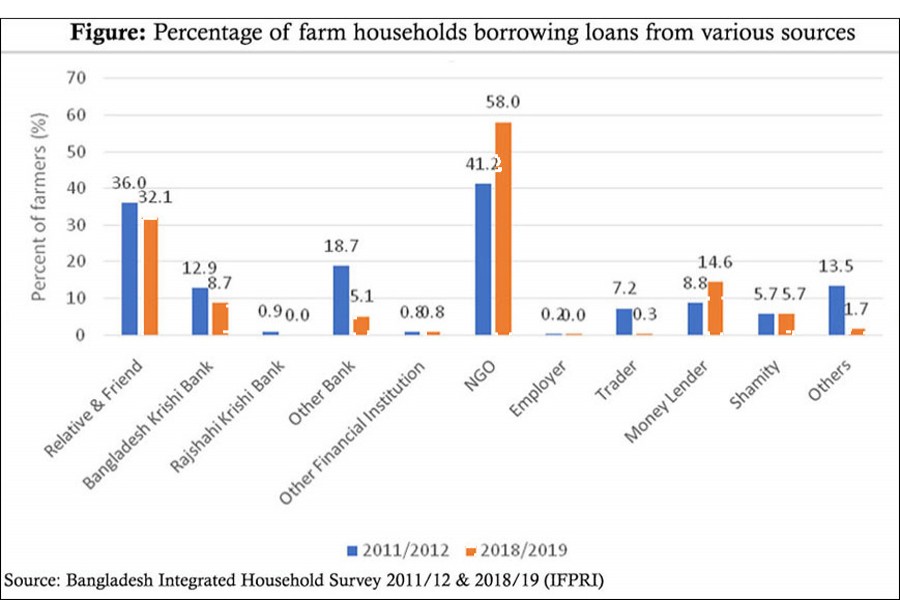

The data from panel survey also supports this piece of information. The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) has conducted the Bangladesh Integrated Household Survey (BIHS) which is a nationally representative three round panel survey of rural Bangladesh. The survey collected data on rural farm households' source of obtaining loans during the 12 months prior to survey rounds. The figure shows the percentage of farm households borrowing loans from various sources.

The baseline and end line data represented in the figure above shows that the most popular source for obtaining loans for farmers has been informal sources such as relatives and friends and non-government organisations (NGOs). Banks and other financial institutions are lagging quite a bit in this aspect, according to data collected in both 2011/12 and 2018/19.

We want to dig deep and understand the difference between the general process of obtaining agricultural loans from formal and informal sources. Our initial hypothesis was-- maybe due to knowledge gap and systemic barriers farmers are failing to obtain loans from formal sources at a lower interest rate and going to the informal loans to secure their financial necessities. Research suggests that obtaining loans from banks may take one to three months as it requires complex paper work. On the other hand, obtaining loans from NGOs or micro finance institutions (MFIs) requires one to two weeks' time. Even though it requires less time and paper work compared to banks, but it comes with significant monitoring pressure and perhaps the NGO loans are also not quick enough to capture the rapid nature of agricultural loans and seasonal markets. On the other hand, obtaining loans at exorbitant rates from money lenders or Mahajans may take about two days only as no paper work is needed to obtain such a loan. Moreover, farmers reported that obtaining loans from formal sources requires some upfront fees as well.

The central bank has a mandate that farmers would no longer be required to submit papers proving their ownership of land, especially to help farmers who worked on leased properties. But it has been speculated that banks and MFIs ask farmers for documentation indicating as internal regulations. It is difficult for farmers to produce required documents to the bank. Moreover, some financial institutions require title deeds (dolil) as mortgage for loan size even below Tk. 50,000; while some other institutions ask for minimum 1 acre of land as requirement, which is impossible to provide for marginal, landless and tenant farmers. Bankers opined that due to high default rates in agricultural credit, the banks are forced to follow these stringent measures.

The NGOs and MFIs are better options for farmers in terms of lower interest rates compared to informal money lenders. The NGOs and MFIs are also performing better in terms of managing defaults in agricultural credit as they have agents in the field to collect repayments and monitor the farmers.

Farmers' credit demands are usually instant, and these requirements need to be fulfilled almost immediately. There may be a pest attack for which there is an immediate requirement of pesticide or an ensuing natural calamity like flood or cyclone and a farmer may need to employ workers and engage in early harvesting. These workers are usually day-labourers and need to be paid after the day's work. If a farmer needs to borrow to pay for these input items (e.g., pesticide, day labourers' wages), he goes to the loan sharks, from where he can borrow in almost no time and pay for the immediate action items.

Even under normal circumstances, a farmer may need to borrow some money to pay for the seeds and fertiliser during the early stages of cultivation. But s/he cannot wait for one to three months to obtain loan from formal banking system and produce all the required documents (e.g., NID, land deed etc.) to process it. Moreover, even though a farmer inherits a land or cultivates in a family owned agricultural plot, s/he is not necessarily the owner of the plot or has his or her name on the land deed to prove that s/he is entitled to utilise the plot. This may be another reason for farmers going to the NGOs/MFIs or money lenders for loan. Sometimes farmers buy input on credit from the input dealers which may turn things for the worse if they are already in debt. Often farmers even borrow to maintain the schedules of loan repayment. Ultimately all these financial pressures lead the farmers to sell their produce soon after cultivation, at time a when the overall market price remains low. Not being able to receive fair price adds to their plight; they fall more deeply in the vicious circle of poverty and debt. Therefore, the small and marginal farmers are always trapped in a state of financial despair and necessity.

So, what can be done in this aspect? If we want to come up with a short answer to the complex problem discussed above, the answer would be increased financial literacy among the farmers and the use of digital technology so that farmers can access financial support more readily. Farmers should be provided with training on financial literacy so that they can take decisions more knowledgably. Use of mobile financial services to disburse and repayment of loans should be introduced by public banks. Moreover, fair price of agricultural products and quality inputs should be ensured for marginal and small farmers. A cohesion among the aforementioned policy changes can give some hope to our financially burdened farmers.

Md Sadat Anowar is a Research Analyst at the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

sadatanowarsunny@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.