Published :

Updated :

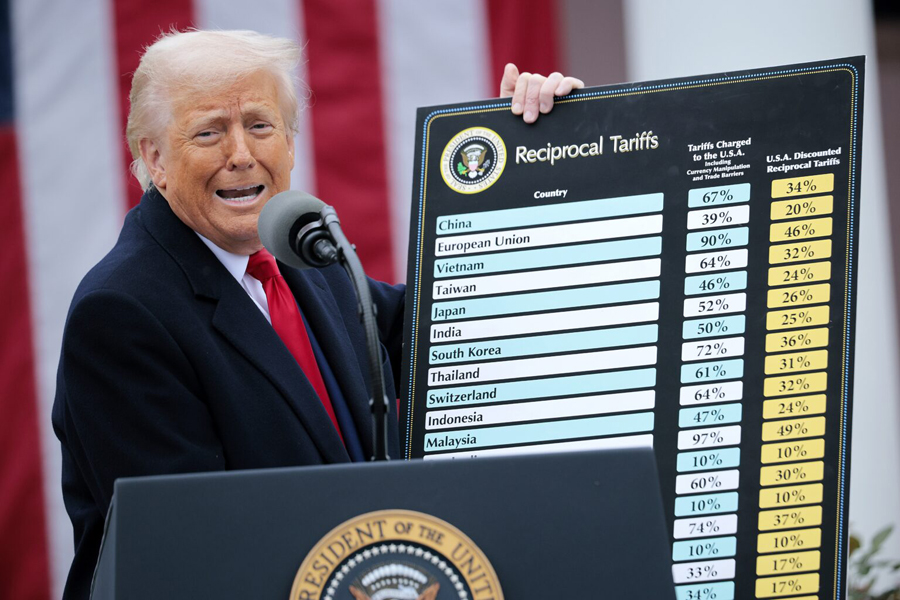

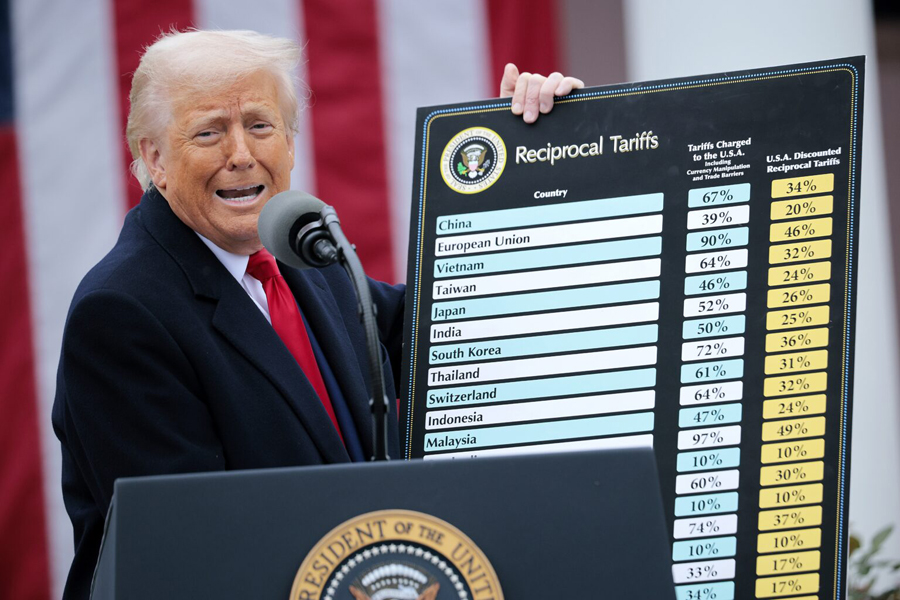

The tariff policies of Mr Donald Trump are creating chaos in the international trade world. This is most particularly true in the garment business. The clothing sector is competitive with many countries producing some kind of wearing apparel. This is different than the automobile industry where there are a limited number of producing companies. The industrial economies purchased from the developing economies most of their garments, covering a wide range of products.

Two big changes are taking place in this sector: the imposition by the United States (US) of high tariff levels that vary from country to country. Second, the changing role of China in the market as Chinese clothing products shift to the European apparel market away from the US. In this respect Chinese manufacturers are also attempting to enter the US market through subsidiaries in other countries such as Vietnam or Cambodia.

Since becoming president in January 2025 Trump has issued many new rules related to US tariffs. These rules are characterised by being different for each country, tossing out the Most Favoured Nation (MFN) clause, a fundamental principle of international trade. Furthermore, there are frequent changes in these rates so final tariff levels remain uncertain. Trump also uses the threat of tariffs to force other nations to bend to his will. The constant threat of such actions creates uncertainty. This approach in itself discourages international trade as it becomes difficult to predict what tariff levels will be at any time in the future. Without certainty of the tariff rates for Bangladesh, American garment buyers have reduced or suspended orders as they wait for announcement of final tariffs rates. They will have to pay when products arrive at the US port; there is little certainty of when final agreement will be reached. The Trump presidency uses administrative uncertainty and complexity as a device, a deliberate attempt to reduce imports to the United States. This disruption of international trade during the last six months resulted in reduced orders by the US buyers. Imports from Bangladesh during this period have increased in expectation that tariffs are going up. Thus, inventories have increased, expecting that orders will be limited for the second half of 2025 by which time tariff rates will be stabilised. Buyers make order decisions based on knowledge of the alternatives.

Bangladesh exports garments to two major markets: North America and Europe. The world capacity to produce garments tends to exceed demand as entry is inexpensive and marketing channels are open to newcomers. At present the production capacity is increasing in India, Cambodia and Sri Lanka. At the same time the US has restricted imports from China by imposing high tariff levels. There are also restrictions on the use of cotton from certain areas of China where the US believes there is forced labour engaged in cotton production. These expected shifts of demand in the market have not yet emerged due to the uncertainties about final tariff rates. Turning to the European market we see increasing competition as China raises its sales of goods that formerly were directed towards the US. At the same time countries such as Bangladesh are fighting to increase their market share in the European market. This leads to increased competition in the large European market for clothing. The American market in contrast is wrapped in uncertainty and stagnating. All of this makes it very difficult to come to a reasonable assessment of how these markets will develop and the success or failure of Bangladesh in expanding its trade. Another factor that will play an increasing role in the industry is the introduction of AI to displace labour. This change in technology means it becomes increasingly feasible to produce more types of garments in the US or Western Europe, now impossible due to high wage rates. Technology change is now spreading rapidly in the RMG sector reducing the amount of labour required. The low wage advantage of countries like Bangladesh is fast dissipating. Unless Bangladesh increases its automation competitiveness will decline. The changes of tariff rates initiated by the United States combined with the technological change in production makes the future of the RMG sector particularly uncertain.

We now attempt to estimate the impact of the Trump policies on Bangladesh exports. We consider three levels for reciprocal tariffs : 20 per cent, 25 per cent, and 30 per cent. In addition, we consider three levels of adjustment of margins by manufactures and buyers (wholesale and retail). These are: 0 per cent, 5 per cent, and 10 per cent. This is the combination of: reduction by the Bangladesh factory selling price; the buyer mark-up (costs include transport, warehousing and mark-up in USA); retail mark-up over price from buyer.

There are three effects that one must take into account: First, the change in price in the garment price in the US market brought about by the tariffs and adjusted mark-ups. Second, the impact on the demand for apparel due to changes in the consumption (household income) level. Finally, how the demand for Bangladesh garments in the US is affected by the price and quality of garments from other supplying countries. We expect that the higher prices caused by tariffs will reduce the demand for clothing; we expect the lower GDP level in industrial countries induced by the changes in tariffs will lower the demand for clothing. Finally, we think that the competitive effects well draw garment sourcing away from Bangladesh to other countries such as Vietnam, India and Sri Lanka.

Estimates by the Yale Budget Lab project the increase of the retail price of garments in the United States with the existing tariffs (as of July 21, 2025) will exceed 35 per cent. We estimate the price elasticity for garments is -0.3 (A 1 per cent increase in price will reduce demand by 0.3 per cent). Hence a 35 per cent price increase would lead to a decline of garment demand by 10.5 per cent. (This excludes income and competitive effects.) We expect GDP levels in the US to increase more slowly as a result of the Trump tariff regime. The recently passed Big Beautiful Bill (BBB) may increase the economic growth rate by a small amount. The Trump administration thinks that this increase will be substantial, but the view of most economists is that it will be very limited. Both effects are small and their difference even smaller. We assume then that the negative impact of the high tariffs in reducing income will be offset by any increases in income arising from the BBB. Thus, the total impact of Trump's economic policies on household income will be zero. (The BBB prevents taxes from rising so leaving income level as at present.) Finally, there is the potential shifting from one country to another as the tariff impact is not uniform. We expect a reduction in demand from shift to sources other than Bangladesh. This shift depends on the reciprocal tariff rate. For the three levels of the rate we assume a negative competitive shift of 1 per cent, 2.3 per cent, and 3.6 per cent, the effect increases with the reciprocal tariff faced by Bangladesh. The following table sets out an estimate of the percent decline of exports from Bangladesh to the United States for different reciprocal tariffs and adjustments in mark-ups.

For example, with a 25 per cent reciprocal tariff and a 5 per cent reduction in margins we expect exports to decline by 9.3 per cent. That is about $750 million. Examining the table the decline in demand ranges from 3.6 per cent to 12.6 per cent.

In addition to the tariff regime that Trump has introduced he is involved in deporting illegal immigrants. The numbers here are very uncertain. Data from US Census suggests that there are 400,000 Bangladeshi residents in the US. Of whom we estimate 200,000 are illegal. The 400,000 immigrants are transferring $4 billion a year or $10,000 each per year. ($3billion goes through the banking system and $1 billion through the hundi.) We can expect over the next two years almost all illegal immigrants will be deported. This suggests there will be a loss of about $2 billion per year in remittance flows from the US to Bangladesh of which $1.5 billion would have gone through the banking system. Remittances to the US rose rapidly in the past year to about $5 billion but this we believe represented an attempt by illegal resident Bangladeshis to send their money out of the country before the Trump anti-immigrant policies affected them. Further, we have not included the impact of the new 1 per cent remittance tax (applies from January 1, 2026).

We estimate the decline in foreign exchange earnings from the Trump economic policies, including both the deportations of illegal immigrants and the high tariff imposed will total $2-2.5 billion a year, mostly from reduced remittances. This amount is net of the imported components of Bangladesh exports. This is a substantial amount but growth in the export sector can replace this loss within a few years. Many garment manufacturers will be hard hit by the decline in exports to the United States if they reduce price of garments sold to buyers. For example, a shirt sold for $10.00 arrives at the US port worth $11, pays 15 per cent duty and the total mark-up of buyer and retailer, that we take as 90 per cent. The retail price is $24.04. If the reciprocal tariff is 25 per cent the retail price increases to $29.26. The increase is $5.22. The buyer will try to get the Bangladesh factory to reduce the selling price. For example, in the case we are discussing assume the buyer persuades the factory owner to reduce his price by $1.00. This reduces the retail price of the shirt to $26.60. But a reduction by 10 per cent ex-factory price would ruin the owner; factories are earning less than 5 per cent on their margins so can hardly afford pressure from their buyers to reduce prices. Earnings in the garment sector have been reduced by the rising cost of imported raw materials, forced use of diesel, and a higher interest rate.

This analysis suggests that the situation can be managed by Bangladesh. GDP growth already close to zero will remain low for another two years before export growth and increased private investment drive a higher growth rate.

The other aspects of the trade negotiations with the US focus on the extent to which Bangladesh should make a major effort to artificially increase imports from the US. The main motive here is to persuade the US authorities to impose a low reciprocal tariff. What we have written elsewhere about the problem leads to five conclusions that the Government should consider. First a serious effort must be undertaken to reduce the anti-export bias from the current tax system. This means sharp reduction in the present levels of protection. Increasing imports as well as exports and enabling the growth of a larger manufacturing sector. Bangladesh should not abandon the MFN rule. Trade with the US is important but it is still a relatively small share of total trade and disrupting trade with China and India by giving the US exports favourable treatment is not in Bangladesh's interest.

Second, a PSI program should be established to check all import prices of goods and services procured by the export sector. Third, one may try out an arrangement to increase use of US cotton; try to expand military procurement from the US and expand the Biman fleet.

Fourth, more attention to the issues that will raise productivity of the RMG industry. The first point is to establish a regulatory organization to oversee the RMG sector. This organisation would be responsible for regulating actions needed to improve sector productivity. Although probably opposed by the RMG business community the real situation is that the garment manufacturers do not speak with one voice and there are differences in interests according to the size of the factories and their concentration on North American or European markets. This regulatory organisation would be responsible for overseeing and driving actions needed to improve sector productivity. This begins with improving the electricity supply both in reliability and quality; it also must ensure that gas is available as required by the industry; regulation of water use regimes, recycling and proper treatment of chemicals by increased monitoring will be enforced. The successful program to improve safety for the factories needs to continue. Every effort should be made to increase the amount of automation in the factories and train the workers to manage such machines. Much work remains to be done to develop a system of setting wages in the RMG sector acceptable to both labour and management. These arrangements must enabled disputes to be settled without disruption of the factory work; avoiding taking issues to the labor tribunals. Another problem which receives insufficient attention is managing the large volume of non-performing loans in the garment sector. This situation blocks the flow of credit to the factories; partly working capital absolutely essential for the industry to perform but also fixed capital investments to expand capacity and raise productivity. So many factories have classified non-performing loans making it impossible for banks to lend to the factories under present rules. In order to ensure continued increase in productivity, investments are absolutely necessary. Solution to these problems are urgent. It is essential to reduce the amount of under invoicing as it currently distorts the trading system. RMG sector needs correct invoicing for imports of machinery as well as imports of raw materials and other items required for production.

The fifth is keep the management of the exchange rate by Bangladesh Bank flexible perhaps, to move towards planned under valuation to support the export sector. This is a highly controversial area but following the IMF rules will lead to failure to develop the required export growth.

The major conclusions from this article are: first that the total loss of foreign exchange from Trump's policies will be manageable. The second point is that a regulatory organisation is needed for the RMG sector to tackle the portfolio of issues mentioned above.

Dr Forrest Cookson, economist, Development in Democracy. forrest.cookson@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.