Published :

Updated :

A day before 7 March fifty-three years ago, as a student of Senior Cambridge in distant Quetta, Balochistan, where our family lived owing to my father's posting in the garrison town, I looked forward to listening to Bangabandhu's speech the next day. He was scheduled to speak at the Race Course in Dhaka and I expected to tune in to Dhaka Radio and hear him speak.

With the newspapers already speculating whether he would declare Bangladesh's independence on the day, I was in a state of feverish excitement. Besides, foreign radio channels such as the BBC and VOA all waited for a dramatic announcement by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in Dhaka. In Quetta, the Bengali families, rather few in number, looked forward to the Race Course speech. There was too the worry in some of them about the fate of Bengalis in West Pakistan should independence be declared by Bangabandhu.

For me, teenager that I was, it was a dramatic era to live in. Having followed the trajectory of Bangabandhu's politics since I began to follow in 1968 the proceedings of the Agartala Case in Dawn and the Pakistan Times, two leading English language newspapers in West Pakistan, I somehow convinced myself that on the afternoon of 7 March I would no more be a citizen of Pakistan but a citizen of a brand new country called Bangladesh.

Throughout 1970, I had assiduously followed the election campaign in both wings of Pakistan, hoping that the Awami League would win the election. Even so, I was not so sure because there was the combination of right-wing parties which might prevent an Awami League victory by collectively garnering more seats and votes and so blocking the Awami League from assuming power. In the course of the election campaign, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman visited Quetta in July as part of a whirlwind trip through West Pakistan.

By a beautiful working out of circumstances, I had an opportunity not only to meet Bangabandhu on his Quetta trip but also have dinner with him and collect his autograph. That meeting remains a defining moment in my life. A few days before the election, I collected a very large number of Awami League election badges, with the image of the boat in the centre, from the local office of the party. I distributed them among our family and my friends.

On the evening of 7 December 1970, my father and I tuned in to Radio Pakistan --- Quetta did not have any television at the time --- to listen to reports of the election results as they came in. It was a freezing winter night and the fireplace crackled with burning coal, warming the room. The radio stations were announcing the results in Bengali and Urdu. My interest was in the vote in East Pakistan. Once they began to come in, it was sheer joy, for everywhere the Awami League was winning. Every time a fresh result was announced, I loudly told my father, who had decided to go to bed but was yet awake, about it. And so the night went on. I stayed awake till dawn.

The rest is history. And history too is the story of all the intrigue which subsequently went into an undermining of the election results. It was extremely disturbing to see Zulfikar Ali Bhutto unabashedly doing everything possible to prevent Bangabandhu from taking over as Pakistan's first elected Prime Minister. Despite Bhutto's histrionics, people still felt the National Assembly session, scheduled for 3 March in Dhaka, would go on. But early in the afternoon of 1 March, I heard the radio announcement that President Yahya Khan had postponed the session.

Dhaka, as we gathered from the newspapers, was in turmoil. It was in such circumstances, building up hour by hour, that we in Quetta waited to hear Bangabandhu declare Bangladesh's independence. On 6 March, at recess in school, I let my friends know that the next day they and I could be citizens of two different countries. I was truly looking forward to that circumstance. I did not worry about what might happen to Bengalis in West Pakistan should a declaration of independence come to pass.

The next day, 7 March, my father asked me to log in to Dhaka Radio, which was expected to broadcast Bangabandhu's speech live from the Race Course. I tuned in, but there was nothing about the speech. I kept myself linked to our family transistor. Nothing, absolutely nothing. It was then that my father voiced the suspicion that the martial law authorities in Dhaka might have stopped the speech from being broadcast live. He would be proved right.

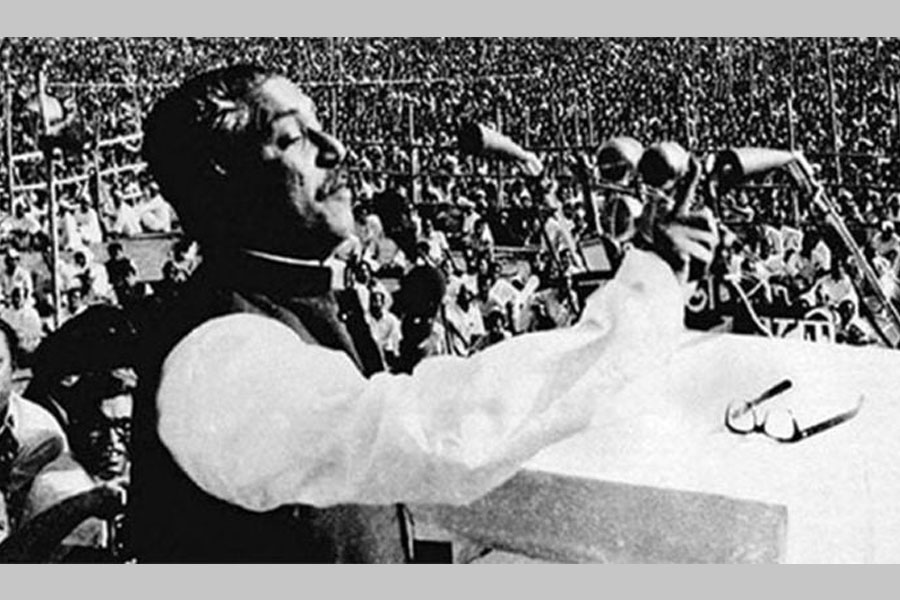

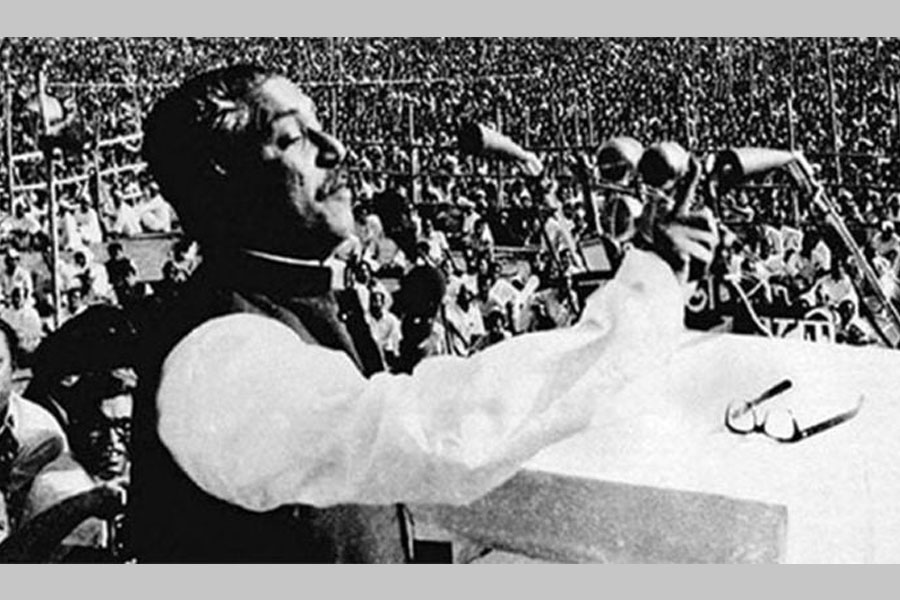

We finally heard Bangabandhu speak the next morning. Waking up early on 8 March, I grabbed hold of the transistor and hoping that there might be something about the speech on the radio, I moved the needle to Dhaka Radio. And there was the announcer letting us know that Bangabandhu's recorded address was about to be broadcast. I roused my father from sleep and together our whole family, including my younger siblings, heard Bangabandhu speak. We were transfixed by his oratory. It was our moment of pride, for here was our leader speaking to us. He did not declare independence, but he pointed out the road to freedom.

In the days following 7 March, I felt thrilled as a Bengali. I could feel that Bangabandhu was no more interested in assuming power in Pakistan but was working toward a peaceful and constitutional way out of Pakistan for us Bengalis. I pored through the newspapers, not letting any report on the developing crisis miss my eyes. On the evening of 26 March, as we waited to hear General Yahya Khan announce a transfer of power to the Awami League following the talks in Dhaka, we were shocked to hear him take the incendiary steps he had decided on.

Our family left Quetta for Karachi en route to Dhaka on 3 July 1971. A day earlier, taking leave of my friends and teachers at my school, I politely informed them that the next time I visited Pakistan (I deliberately did not use the term 'West Pakistan'), it would be as a citizen of a sovereign Bangladesh.

I made my very first visit to Pakistan, to Lahore and Quetta, in December 1995. I have been there three more times since. Every visit has been a matter of pride for me, as a free Bengali. On my visit to Quetta in December 1995, a couple of my teachers reminded me of my farewell comments in 1971 and told me: 'You have indeed come here as a citizen of an independent Bangladesh, haven't you?'

I was happy beyond measure.

ahsan.syedbadrul@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.