Published :

Updated :

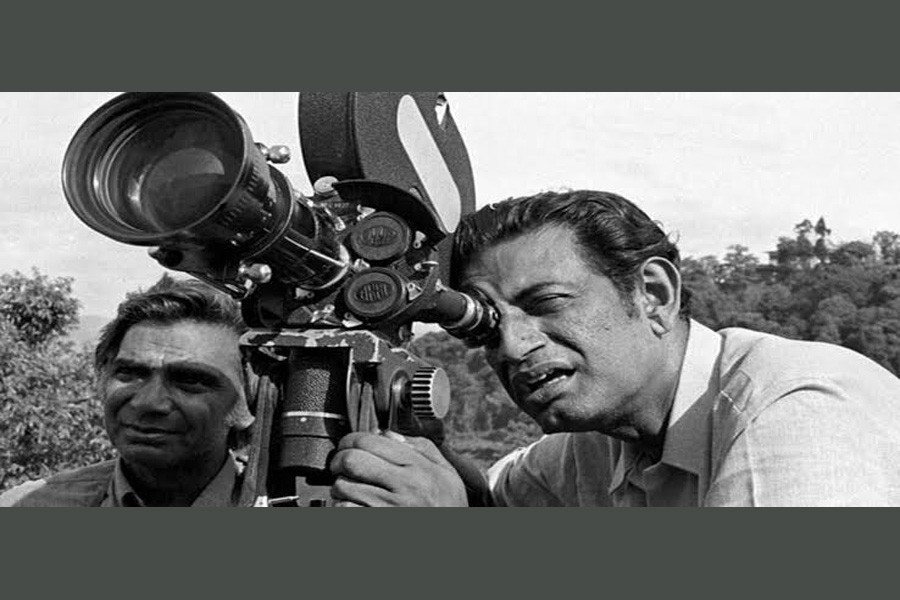

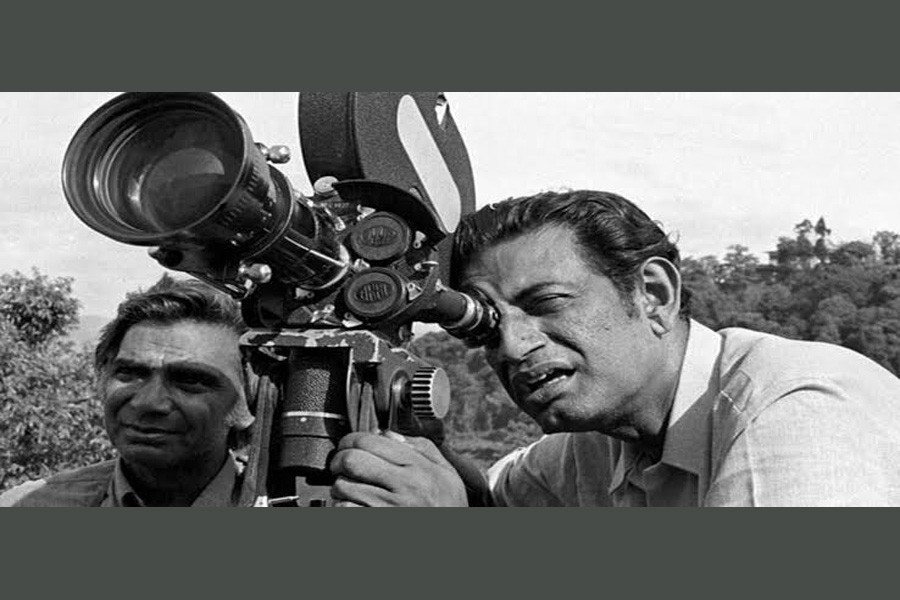

Like 'total authors', a moniker used for writers consummately dedicated to literary activities, Satyajit Ray was also a total film-maker. Although he was basically a painter, a music connoisseur well-versed in Indian and Western classical music, in his 36-year career of film direction, Ray proved himself a pure movie-maker. In 2021 the world's film circles celebrate his birth centennial. The Bengalee film stalwart (1921-1992) has already been acclaimed as one of the 10 greatest directors of all time. Making his debut with 'Pather Panchali' in 1955, Ray directed a total of 36 movies. They include 29 feature films, 5 documentaries and 2 short-films.

Befitting a pure artist ---in the broader sense, Satyajit Ray has never allowed himself to be distracted by any mundane passion. Cinema was his sole preoccupation. That this medium would be his life-long love had its early signs during his youth. While he was in the profession of copy writing at an advertising firm, Ray and a few youths founded the Kolkata Film Society. It became popular soon, with its membership increasing by the day. The sole task of film societies is arranging shows of modern and off-beat and all-time great classical films. At intervals, they organise seminars, open discussions etc on the movies shown. The movies are collected from different sources, especially foreign missions. According to Ray specialists, the film society days played a great role in shaping the movie taste and temperament of the future film maker.

That Ray's very maiden film 'Pather Panchali' (1955) would emerge as a landmark in the world cinema could be sensed by the people close to him. They could realise that the tireless efforts to collect and screen overseas classical movies were the clear signs of the film lover turning finally to movie making. It didn't take long for it to happen. Ray invested all his creativity and love for the plastic arts into his first movie made on a shoestring budget.

With 29 feature films and four documentaries to his credit, lots critical and viewers' reaction made rounds about his artistic stance on life. If one keeps the Opu Trilogy, the three films revolving round the child Opu, the adolescent Opu and the young man Opu, the director is found exploring the inner meanings human existence. After the child Opu's father and mother set out for an uncertain life, leaving their village home behind, with the teenage sister Durga dying suddenly, the little boy steps into an adverse world. The father dies in Varanasi in 'Oporajito', the sequel to 'Pather Panchali'. It forces the widowed mother and teenage Opu to take shelter in the village-home of a distant relative. A brilliant student at school, Opu faced no difficulty in getting admitted to a college in Kolkata. But living in the big city becomes quite difficult unless one has the means to meet the expenses of one's food and lodging. Since he is a brilliant student, Opu can manage a part-time job at a printing press. The manager, satisfied with Opu's performance allows the college student to enjoy work-free time to prepare his class lessons. Opu comes out of college with good result. In 'Opur Sangsar', the last part of the trilogy, the young man is able to win the motherly heart of the landlady, who has rented out to Opu a single dingy room on the first floor of her worn-out residence. Earlier, adolescent Opu's mother had died in the village. Opu was alone in this vast world. Except office colleagues, mostly clerks like him, the young man had none to even talk intimately to. The real struggle in life and a series of trauma, especially after the death of his newly married wife, changes radically his attitude towards human existence.

Originally based on a novel by Bibhutibhushan Banerjee --- 'Pather Panchali', the first part of the trilogy, portrays the tranquil natural beauty, the innocence and folksiness of people, until the father is back from town. The mood changes after he learns about the death of his beloved young daughter Durga. The following two parts comprise Ray's detailed portrayal of poverty, destitution and a pervasive pathos plaguing the life of the protagonist Opu - the last part's Opu acted out by Soumitra Chatterjee. These portrayals of bitter reality have led a section of critics to call Satyajit Ray a director committed to life. It leaves wide space for misinterpreting Ray's real attitude towards life. For the term 'commitment' attains different meaning and connotation in different contexts. Moreover, no practitioner of the arts can expect to thrive without a commitment. Although in the realm of hard politics the notion of 'commitment' alludes to activism, a pure artist finds it essential for his or her continued growing into maturity.

Although the director has never touched upon the subject directly, Satyajit Ray has been found to be politically conscious in nearly a dozen films. Ironically, the left critics have found reactionary and compromising elements in his movies. Apparently, they expected Ray's films to be filled with contents of dissent and calls aimed at the masses to revolt against the prevailing exploitative system. But Satyajit Ray had never been overtly radical, nor had he ever felt inclined to disseminate a caustic message. Perhaps Mrinal Sen is there to perform this socially crucial task. Ironically, Sen appears also tiring to a section of viewers with his often-explosive messages expressed without sacrificing his distinctive symbolism. Many critics and a large segment of the movie lovers never stop comparing Ray with Sen. They do this when they keep the two talented directors side by side in the genre of 'protest cinema'. It's natural in the age of the 20th century radicalism popular with the educated and Castro-Guevara admiring romantic youths. These urban youths are different from theoretical dissidents. They found Sen's direct messages time-befitting and inspiring. Ironically, many are also ready to acknowledge that Sen's typical style of conclusions at times seem repetitive, and also hackneyed. Ray's movies hardly make one feel bored. His audience is composed of mostly aesthetes and mature people. There is little space for one to feel like jumping on the bandwagon of social restructure after watching a politically tilted Ray movie.

The activism of Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen is different. Sen is found impatient from the start of his films to get his message across. Those acquainted with Sen's politically vocal movies can sense in a gap of a few sequences in any of his film the prologue to the message. One can readily cite the instances of a number of such films directed by Mrinal Sen. The films include 'Interview' (1970), 'Calcutta 71' (1972), and 'Padatik' (1973). The story-line of all the three movies is based on the Kolkata mega city in the 1970s.

The seemingly non-stop political turbulence, coupled with the left extremists' violent war on the 'class enemies', and the merciless police operations against the 'Naxalites' ruled the roost during the period. Kolkata in those days turned into a city of panic and nightmares. The silent and helpless victims of that critical time turned out to be the city's middle class. By nature a non-conformist and radical, Mrinal Sen didn't waste time to pick the Kolkata of the 1970s as the subject of a number of his remarkable movies, besides the 'Calcutta Trilogy'.

Many serious movie-goers are not aware of a vital fact. Except his close circles, lots of Ray fans do not know that the socially conscious and impeccably humanitarian Satyajit Ray began thinking of making a full-length feature on the Kolkata of the late 1960s-`70s much ahead of others. He made the movie 'Pratidwandi' in 1970. Seeing its warm audience response, he directed the second and the third films on the similar theme --- 'Seemaboddho' (1971) and 'Jana Oronyo' (1976). All these three films finally made what was later known as the Ray Trilogy. Though known as a film-maker with a classical temperament, Satyajit Ray had all along been a politically conscious artist. Also history-conscious, he didn't want to remain confined to the Kolkata realities. Finally, he turned to the restive days of the Indian Independence movement as depicted in the fictions and short stories by Tagore, with Bengal in focus. The outstanding films include 'Charulata', 'Gharey Bairey' etc.

Ray loves to put added stress on the interpretation and dissection of reality before coming to a conclusion --- sarcastic, pitiful or that filled with stoic indifference. The 29 feature films directed by the master director mostly uphold human virtues. Resembling great artists in different mediums, Ray has tried to assess man in different situations. In 'Jalshaghar' he tried to portray the helplessness of a decadent feudal lord. On the other hand, he attempts to release his childhood world of subconscious fantasies in 'Gupi Gaen Bagha Baen' and 'Hirok Rajar Deshe' --- the latter acclaimed also as a political satire. Man's state of bafflement amid the vastness of the Himalayan nature finds spontaneous expression in 'Kanchanjangha'. Ray's creative sensibilities fan out to the furthest possible limits of human capabilities to explore the mysteries of existence. At the same time, he was conscious both politically and socially. Many of his films bear witness to it.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.