Published :

Updated :

Most people here in Bangladesh and abroad grew up learning from the media that when the central bank (CB) increases the money supply, interest rate decreases and the opposite happens when CB decreases the money supply. This has been misleading some people thinking that money supply (Ms) and interest rate (r) are inversely related. Although the outcomes of CB’s action are realised as intended, the inverse relationship is indefensible and outright wrong. The correct statement is that the money supply and interest rate are positively related following the microeconomic theory of law of supply.

Another misnomer that is current among people is that the CB prints currency to change the volume of money supply in the economy. In practice, currency and coins are supplied through the banking system for ease of transactions for goods and services – not to change the money supply. There are two reasons why currency is printed: (i) to replace damaged currencies; and (ii) to meet peoples’ demand for currency.

An increase or a decrease in money supply is a mechanism in which the banking system and the public are intertwined. Understanding this mechanism would help us know how a country’s CB tries to influence the money supply, which in turn influences interest rates, and the economy.

There are three globally recognised definitions of money.

M1 = currency and coins in circulation + deposits in checking accounts (also called demand deposits)= C + DD

M1 = C + DD

M2 = C + DD + TD, (short term time deposits)

M3 = C + DD + TDL, (Long term time deposits).

As one can see M2 and M3 are much less liquid because money in time deposits is locked over a period during which they are not available to use for transactions. For our understanding of the money supply process, we only need the definition of M1 money.

A CB does not create money or increase and decrease the money supply directly. Expansion and contraction of money supply result from a joint action of the banking system, the public, and indirectly by the CB.

The central bank is the supplier of Monetary Base (MB) which consists of reserve money (RM) and currency (C) in the hands of the people outside the commercial banking system.

MB = RM + C

The banking system get these reserve money by selling some of their holding of interest earning government bonds (treasuries) to Bangladesh bank (BB) through a process called Open Market Operations (OMO, repo, and reverse repos) and in exchange receives Bangladesh Taka (BDT) as reserve money. BB is now earning interest on these treasuries while banks are loaded with idle reserves which do not earn any interest. The longer the banks hold these RM, the more opportunity cost they incur. So, banks are now actively looking for borrowers (among the public and the businesses) to extend loans to earn interest income instead of holding those idle reserves. As soon as loans are made to the public or businesses, the proceeds are deposited to the borrowers’ checking account. Hence new money is created.

The borrowers then decide how much to take out of the borrowed as cash, how much to keep in a checking account and how much to invest in time deposits. For simplicity, let us assume the following hypothetical case:

The banking system has Tk 250,000 of reserve money obtained from selling treasuries to the BB through OMOs.

When banks extend loans, and create DDs, they are required by law to hold some percentage of those DDs as required reserves (assume, Rd = 16 %). These reserves cannot be used by banks for any purposes.

The legal required reserve ratio for time deposits (assume, Rt = 5%)

Any reserves that are left after satisfying required reserves are called excess reserves (ER). Banks are free to lend out these ERs. But banks voluntarily hold some idle reserves to meet customers’ day to day cash withdrawal and to meet other contingencies that abound in this uncertain world.

The borrowers generally exercise three choices called “preferred asset ratios” that is, their relative holding of DDs, cash, and TDs. Let us assume that for every added Tk 5 worth of DDs willingly held, it insists upon holding an additional Tk 4 on TDs and an additional Tk 1 of currency and coins. In essence, this means that when the banks provide the public with Tk 10 of new demand deposits via new loan, the public will withdraw Tk 1 in cash and transfer Tk 4 into savings accounts, retaining only Tk 5 of the demand deposits initially received in that form. Let us assume that banks decide to hold Tk 0.50 as excess reserve against Tk 5. All these ratios may now conveniently be expressed as follows:

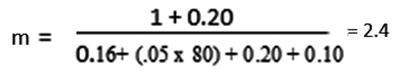

c = C/D, t = T/D, e = ER/D, Rd = 16%, Rt = 5%,

c = 1/5 = 0.20, t = 4/5 = 0.80, e = 0.5/5= 0.10

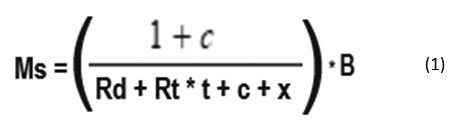

Let us write down the multiplier model of the money supply from my last article (FE March 9, 2024)

Ms= m*B

Change in Ms = m * Change in B

Change in B = Tk 250,000, the banking system is sitting with from selling the treasuries noted above.

Here the factor in the parenthesis is called the money multiplier (m) as also discussed in my article on March 9 issue of the FE. Substituting the values of the parameters from above, we get

m = 2.4

With TK 250,000 excess reserves, the maximum amount of M1 money that can be created by the banking system:

Ms = 2.4 x 250,000 = Tk.600,000 (2)

Now suppose there is an increase in market interest rate based on the supply and demand for loan-able funds (and because of other factors such as capital flight, inflation, and currency depreciation) while everything else about the BB remaining unchanged, that is having no action by the Central Bank (no change in Rd and Rt and no action in OMOs). The market driven increase in the interest rate will affect the parameters of the public’s preferred asset ratio and banks’ excess reserves holding strategy as follows:

With higher market interest rates, the people are likely to hold less currency to reduce their opportunity cost of holding idle cash and deposit it in the banks to earn interest. That causes the C/D ratio to decrease. They are also likely to shift out of time deposits to higher interest earning assets causing a decrease in T/D ratio. The banks are also likely to loan out as much excess reserves as possible to reduce their opportunity cost of holding idle excess reserves so that ER/D will decrease. Under these assumptions, we may assume use the following ratios to hold.

t = 0.70, c = 0.15, e = 0.08, Rd = 0.16, Rt = 0.05

The money multiplier m = 2.7

Ms = 2.7 x 250,000 = 675,000 (3)

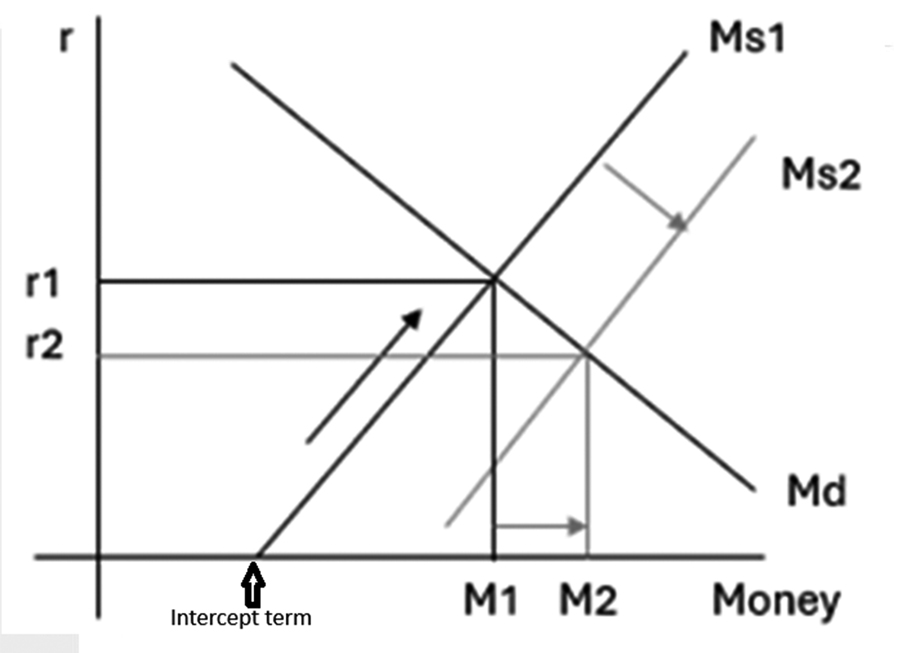

What we found is that as the market interest rate increases in the private sector, money supply increases by 75,000 (compare equations 1 and 2), having no action by the CB (meaning, Rd, Rt and B remaining unchanged). This analysis establishes that money supply and interest rate are positively related – an upward sloping money supply curve (Ms1) like the supply curve of any product in the private economy.

What about the CB’s misunderstood “inverse” relationships between money supply and interest rates?

What happens when the CB increases the banking system’s reserve money, the monetary base increases at interest rate r1 and the banking system’s actions increase the money supply at interest rate r1. The entire Ms1 curve shifts rightward to Ms2 and the new equilibrium interest rate settles at r2 with new quantity of money at M2. The money supply curve is still upward sloping.

Interest rate is the price of money and credit. Like any good produced in the private sector, its price and quantity supplied is positively related. Why would the price of money and the quantity of money supplied be any different?

In the multiplier model of the money supply, equation (1) above, there is no explicit interest rate variable included in the model. A simple linear model of the money supply that I derived for my monetary economics class is presented as follows using the linear relationship between banking systems demand to hold excess reserves (ER) as a function of interest rate:

ER = ER0–a.r

Where ER0 = the amount of excess reserves banks hold independent of the interest rate because banks, by desire, hold excess reserves to meet the condition discussed above. Substituting the ER equation and other definitions given above, a linear model for the M1 money supply is obtained as follows.

Here (a/Rd) is the slope of money supply curve and the remaining expression inside the bracket is the intercept term on the money supply axis. A change in any of the factor inside the bracket will shift the money supply curve.

We now see the presence of interest rate in the money supply model showing the positive relationship between the money supply and the interest rate regardless of what monetary policy activism the central bank pursues.

Dr Abdullah A Dewan, formerly a physicist and a nuclear engineer at BAEC, is professor of Economics at Eastern Michigan University, USA. adewan@emich.edu.

The material in this article are taken from the writer’s forthcoming book, “Politiconomy of Bangladesh”.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.